NI 100: What was in the Government of Ireland Act?

- Published

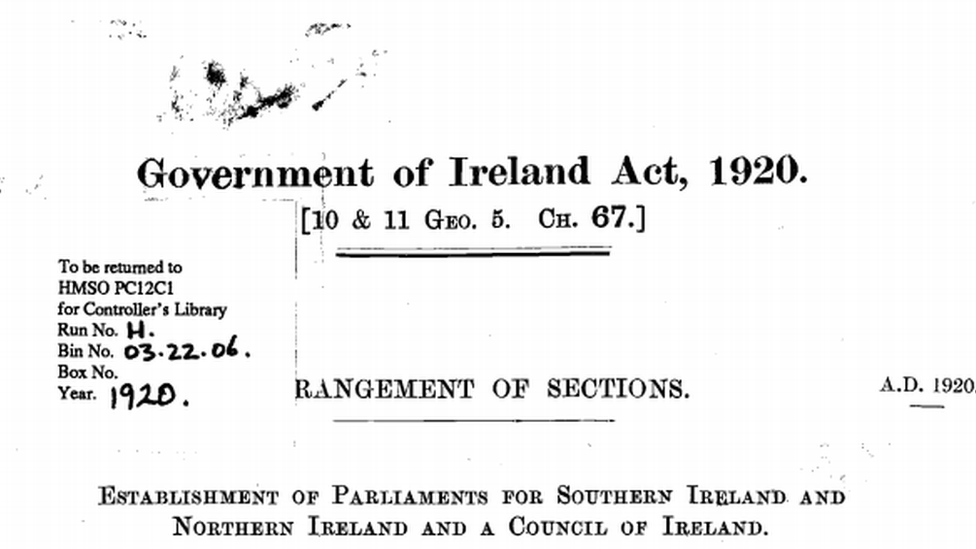

Exactly 100 years ago today - 23 December 1920 - the Government of Ireland Act, external became law.

It partitioned Ireland into two separate jurisdictions - Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. The latter would become the Irish Free State and eventually the modern Republic of Ireland.

Northern Ireland would become the first part of the UK to have what we now call devolution.

But what else did the Act contain?

Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland

In an attempt to reconcile the demands of unionists - the majority of whom lived in the north east of Ireland - to remain part of the UK and nationalists, most of whom by 1920 wanted full independence, the act split Ireland in two.

Both Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland would remain part of the UK but would have their own devolved parliaments.

Each parliament would have a Senate and a House of Commons, but MPs would also continue to be elected to Westminster as well.

King George V opened the new NI Parliament at Belfast City Hall, with thousands lining the streets

A Council of Ireland was also to be set up "with a view to the eventual establishment of a Parliament for the whole of Ireland and to bring about harmonious action between the parliaments and governments of Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland".

It would be made up of the lord lieutenant (the King's representative in Ireland) and 40 other members divided equally between members of the two parliaments.

The Act said that if both parliaments voted in favour of setting up a single Irish Parliament, then the Council of Ireland would be dissolved.

Devolved powers

Both parliaments were to be vested with extensive powers "for the peace, order and good government of Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland".

However, as with devolution today, there were some significant powers which remained with Westminster.

These included laws related to the Crown or succession of the Crown, the power to declare war, powers over the military, the power to make treaties or establish relations with foreign states and laws regarding treason and trade outside of each parliament's jurisdiction.

Other more peculiar exemptions included powers over lighthouses, buoys or beacons and the ability to make laws about submarine cables or wireless telegraphy.

They were also prohibited from making laws which either established or endowed a religion or restricted or prohibited a religion or practice of religion.

Executive authority was to remain with the King via the lord lieutenant, but the Act legislated for each parliament to set up government departments headed by ministers, who would be members of a privy council.

In practice - as would become the case in Northern Ireland - executive authority rested with these ministers, including a prime minister.

Courts

In a similar fashion to the establishment of two parliaments, two court systems were to be established - one for Southern Ireland and one for Northern Ireland.

Each would consist of a High Court and a Court of Appeal.

There would also be a High Court of Appeal for Ireland which would have appellate jurisdiction over the whole island.

Universities... and freemasons

Among what we might consider more unusual aspects of the Act from a modern-day perspective are provisions about universities and freemasons.

The Act stated that "no law...shall have effect as to alter the constitution or divert the property of, or repeal or diminish any existing exemption or immunity enjoyed by the University of Dublin, or Trinity College Dublin or the Queen's University of Belfast" except with approval by the universities.

It also required the Parliament of Southern Ireland to pay £30,000 a year to University College Dublin, £42,000 a year to University College Cork, £26,000 a year to University College Galway and £17,000 "for the general sum of those colleges respectively".

Trinity College Dublin was to enjoy certain privileges under the Act

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was to pay £26,000 a year to Queen's University Belfast.

The Act also stated that existing laws about unlawful oaths or unlawful assemblies did not apply to the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Ireland or of any lodge or society recognised by that Grand Lodge.

A place to call home

Until the Act of Union in 1801, Ireland had its own parliament which had existed from medieval times.

From 1732 until 1800 this parliament sat in Parliament House in College Green in Dublin, which was the first purpose-built bicameral parliament building in the world.

In 1803 the Bank of Ireland bought the building, but it continued to act as a symbol of nationalism.

The Act stated that if the new Government of Southern Ireland wished to take Parliament House back from the bank it would be allowed to, provided it could pay for a new head office for the bank and compensate it for the disturbance of moving.

Ultimately neither the Parliament of Southern Ireland nor its successors ever sat in Parliament House.

Parliament House in Dublin still houses the Bank of Ireland today

The Act also said the Parliament of Southern Ireland must be in Dublin and the Parliament of Northern Ireland must be in Belfast.

This caused problems in Northern Ireland when the new parliament finally identified a permanent site at Stormont, which lay outside the Belfast city boundaries.

The boundaries were later extended to include it.

What became of all of this?

Put simply, most of what related to Northern Ireland came into effect and most of what related to Southern Ireland did not - at least not how the Act intended.

The Council of Ireland also never met.

The Parliament of Southern Ireland sat once, in June 1921, but only four unionist MPs attended the Commons. It elected a speaker and then adjourned and Parliament was ultimately replaced by the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State.

The Parliament of Northern Ireland first met in June 1921 and governed Northern Ireland for almost 51 years until it was suspended in March 1972 and eventually abolished as civil disorder escalated in the early years of The Troubles.

The court system set up in Northern Ireland by the Act continues to exist to this day.

Related topics

- Published21 December 2020

- Published21 December 2020