NI 100: The new state emerges from a tumultuous decade

- Published

Just over a century ago, Ireland was united as one island under British rule. But that was just about to change forever.

With the passing of the Government of Ireland Act by Westminster on 23 December 1920, the island would be partitioned, with new governments to be formed in Dublin and Belfast to oversee two new jurisdictions.

This was the culmination of one of the most tumultuous decades in Irish, and European history and set the path to an eventual Irish Republic.

Below we look at the years between 1916 and 1922 and the key moments that led to partition and the establishment of Northern Ireland.

The road to 1916

In the decades before 1921, the key phrase when it came to Ireland was not independence or partition - it was home rule, in which Ireland would get more say in how it was governed, via a devolved Irish parliament, but still remain part of the United Kingdom.

In the 1880s, Irish politician Charles Stewart Parnell led the parliamentary charge in efforts to secure an Irish government. The first Home Rule Bill was defeated in Westminster in 1886 as well as another in 1893 - but in 1914, a third bill passed.

This was despite fierce anti-home rule sentiment from the unionist population, the majority of of whom lived in of Ireland's north-eastern counties, who felt alienated by the idea of being ruled by a parliament in Dublin.

Edward Carson was the most prominent anti-home rule voice of the era

Their grievance led to the formation of a military organisation, the Ulster Volunteers (later the Ulster Volunteer Force), under the leadership of redoubtable Dublin-born unionist Edward Carson. In response, the Irish Volunteers were formed to underline the demand for home rule amongst many Irish people.

It seemed inevitable that this backdrop of escalating tensions would give way to sustained violence - but the outbreak of World War One turned everyone's attention from Ireland to Europe.

The war's impact on events in Ireland could not have been more crucial, particularly in 1916.

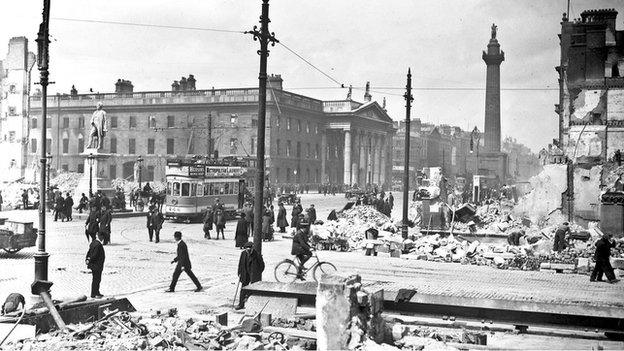

The fighting during the Easter Rising causes considerable damage in Dublin

April 1916: Easter Rising

On Easter Monday, a coalition of Irish rebel forces stand on the steps of Dublin's General Post Office (GPO) and read a proclamation declaring the establishment of an Irish republic.

This is the start of the Easter Rising, in which the rebels sought to assert Ireland's "national right to freedom and sovereignty".

After a week of conflict, in which much of Dublin's city centre is destroyed under a barrage of artillery fire, the rebels surrender.

A total of 450 people are killed, among them 64 rebels. 2,614 were injured, and nine others were reported missing, almost all in Dublin.

The rising does not gain wide support among Irish people. But the British government's decision to execute 15 of its leaders, arrest more than 3,500 men and women and impose martial law throughout Ireland provoked outrage and sympathy for its cause.

Soldiers advance towards Thiepval at the Battle of the Somme

July 1916: The Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme begins - its opening day would prove to be the bloodiest in the Army's history, with a total of 19,240 British troops killed within 24 hours.

Almost a tenth of those who die that first day are from the 36th Ulster Division, a unit mainly made up of members of the Ulster Volunteer Force, formed three years previously to block home rule.

Many expect the death of so many Ulstermen at the Somme to be seen as a loss that would be remembered, and rewarded, by Britain when the issue of home rule came up in the future.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George

July 1917: The Irish Convention

Prime Minister David Lloyd George calls for an Irish Convention with the aim of coming up with parliamentary solutions that would be acceptable to all shades of public opinion.

The event brings together more than 100 delegates - nationalists, unionists (both from Ulster and the south) and many others.

However Sinn Féin, already increasingly popular in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, refuses to participate.

The Irish Parliamentary Party, a party dedicated to securing home rule, agrees to take part but its credibility, already damaged by the swell in popularity of Sinn Féin, takes another hit when the convention failed to reach any agreement by the time it issues a final report in March 1918.

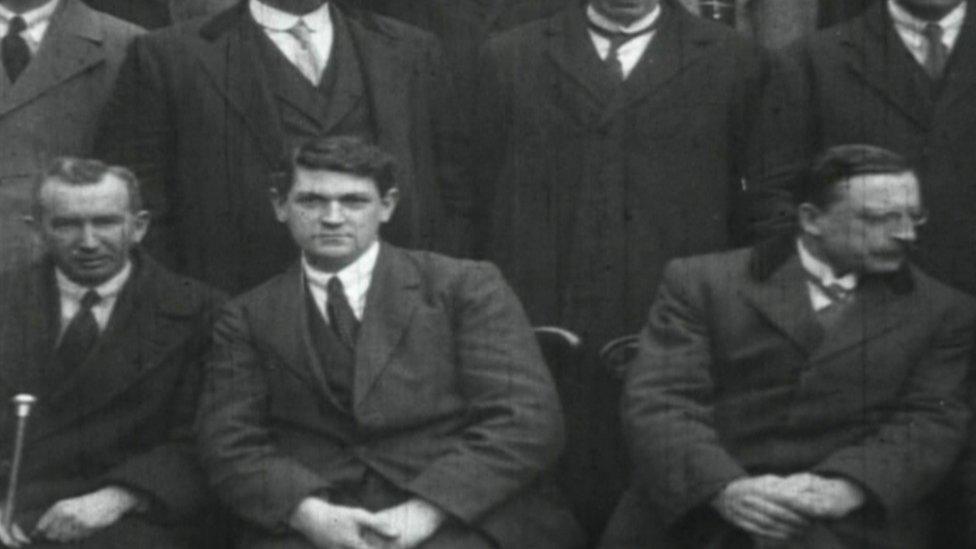

Éamon de Valera (centre) was one of the Sinn Féin leaders earmarked for arrest during the conscription crisis in Ireland

April 18: Conscription crisis

The UK government passes a bill introducing conscription in Ireland, but the backlash unites Irish political parties and the Catholic Church in opposition.

The government faces particular criticism for linking the passage of conscription with the introduction of home rule, leading Irish MPs to walk out of Westminster.

In May, the Lord Lieutenant in Ireland - the highest ranking British official in the country - orders the arrest of 73 Sinn Féin members, including its leaders Arthur Griffiths and Éamon de Valera, claiming that the party is conspiring with German forces against the British.

No evidence of a conspiracy ever emerges.

US involvement in WW1, which helped turn the tide in Europe, leads the government to drop its plans for conscription in Ireland, but the months of strife lead to even more support for the independence-seeking Sinn Féin party.

November 1918: World War One ends

About 210,000 Irishmen served and more than 35,000 were killed.

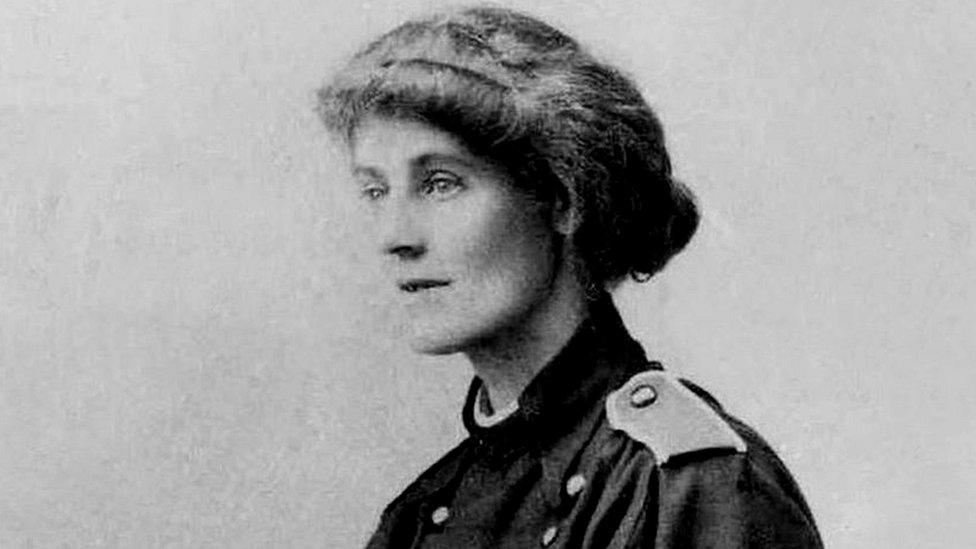

Constance Markievicz became the first ever woman to be elected to Parliament - she and her Sinn Féin party colleagues never took their seats

December 1918: A resounding victory for Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin secures 73 of the 105 Irish seats in Westminster during the general election.

The diminishing Irish Parliamentary Party is almost wiped out, winning only six seats despite previously controlling 67.

The other 22 seats are won by Irish unionists.

Sinn Féin members, as per their manifesto, do not take their seats.

Among them is Countess Markievicz, an Easter Rising rebel held in prison, who becomes the first woman ever elected to Parliament. The party vows to form the first Daíl Eireann (Irish parliament).

January 1919: A new parliament - and a new war

Sinn Féin members form Dáil Éireann, a breakaway parliament that is the first iteration of what would become the modern-day seat of Irish politics. Invitations are sent to all elected Irish MPs, including unionists, but others did not attend.

The members proclaim an Irish Republic and demand British withdrawal from Ireland.

On the same day, 120 miles away in County Tipperary, Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteers, acting on their own initiative, ambush and kill two Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers at Soloheadbeg.

These deaths are considered the first in the Irish War of Independence, a war between British forces and the guerrilla members of the IRA that lasts more than two years and kills about 2,000 people.

September 1919: Long Committee paves the way to partition

With World War One over and the Paris Peace Talks having secured the Treaty of Versailles to officially settle the peace, Westminster's attention once again returns to its commitment of home rule.

However, the task is now considerably more difficult than it was in 1914 when home rule was agreed - both unionists in the north, who want to remain under Westminster's rule, and nationalists in the south, who want complete independence, oppose the move.

David Lloyd George, the prime minister, tasks the Long Committee - led by unionist Walter Long - with recommending how to implement home rule.

It suggests two home rule parliaments, one in Belfast for a new northern state, and one in Dublin for the south.

Unionists come to reluctantly support the move.

These findings would form the basis of the Government of Ireland Act, the legislation that would officially introduce partition into the statute books.

Ulster Unionist James Craig, who went on to become Northern Ireland's first prime minister, was key in arguing for a six-county partition rather than one which included the nine counties of Ulster

February 1920: Bill published

The Government of Ireland Bill emerges on 27 February and, with it, details on partition.

Originally, the Long Committee recommended that the northern parliament control the nine counties of Ulster.

However, unionists who come to support the committee's recommendations instead argue for only six counties - Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone - as those counties had more substantial unionist populations than those in the three other Ulster counties of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan.

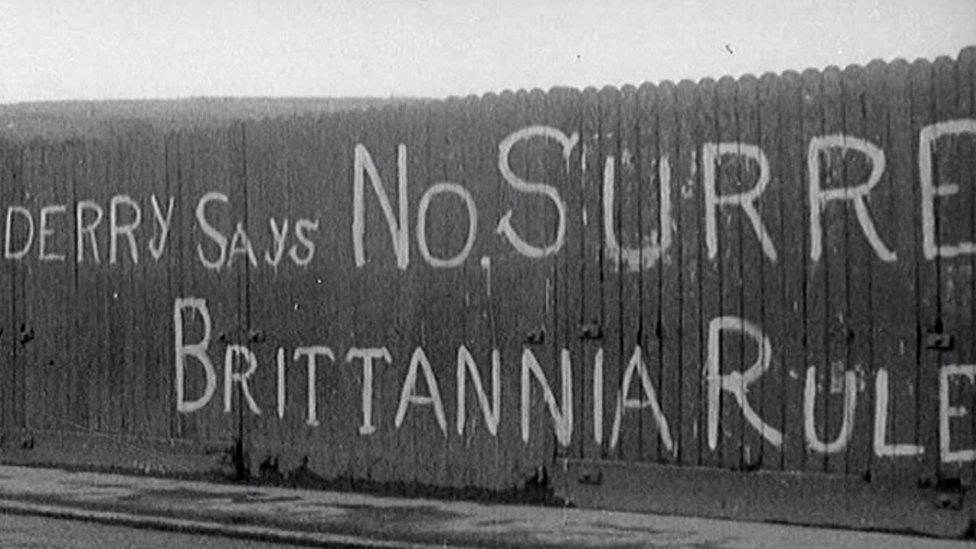

Graffiti in Derry in 1920

Summer 1920: Rising violence in the north

In parts of the north, particularly Belfast and Londonderry, the year had been characterised by spiralling sectarian tensions, which then begin to spill over into significant disorder.

Derry is engulfed in sectarian skirmishes between the IRA and UVF - in one week in June, 20 people are killed and scores more injured.

In July 1920, rioting breaks out in Belfast, the first of what would become regular flaring of sectarian violence. Between this month and autumn 1922, 465 people would die and 1,000 people be injured in the city as a result of the violence.

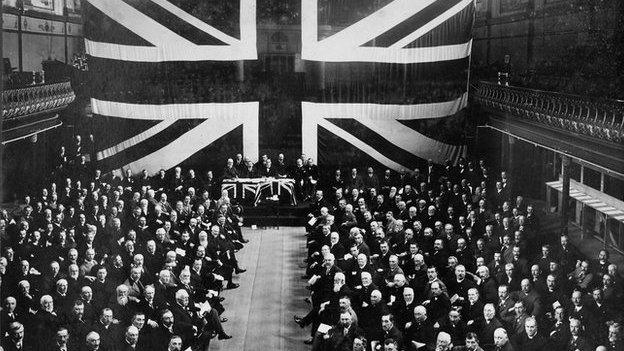

December 1920: Partition green-lit at Parliament

The Government of Ireland Act officially passes at Westminster. It approves the partition of Ireland, with a devolved government in Dublin and another devolved government in Belfast for the six northern counties.

Sinn Féin rejects the proposals but unionists accept them, coming to believe that a devolved administration could look after their interests better than Westminster.

King George V opened the new NI Parliament at Belfast City Hall, with thousands lining the streets

June 1921: Northern Ireland's first Parliament

Following an election in March, Northern Ireland's first Parliament opens in Belfast's City Hall.

James Craig, who has replaced Edward Carson as the leader of Unionism, becomes Northern Ireland's first prime minister.

King George V opens the Parliament by urging "all Irishmen to pause, to stretch out the hand of forebearance and conciliation, to forgive and to forget, and to join in making for the land which they love a new era of peace, contentment and goodwill".

July 1921: Truce in the War of Independence

A truce is agreed between Britain and Irish rebels. Prime Minister David Lloyd-George and Éamon de Valera, the president of Sinn Féin, agree to hold a conference in October for talks over a permanent settlement.

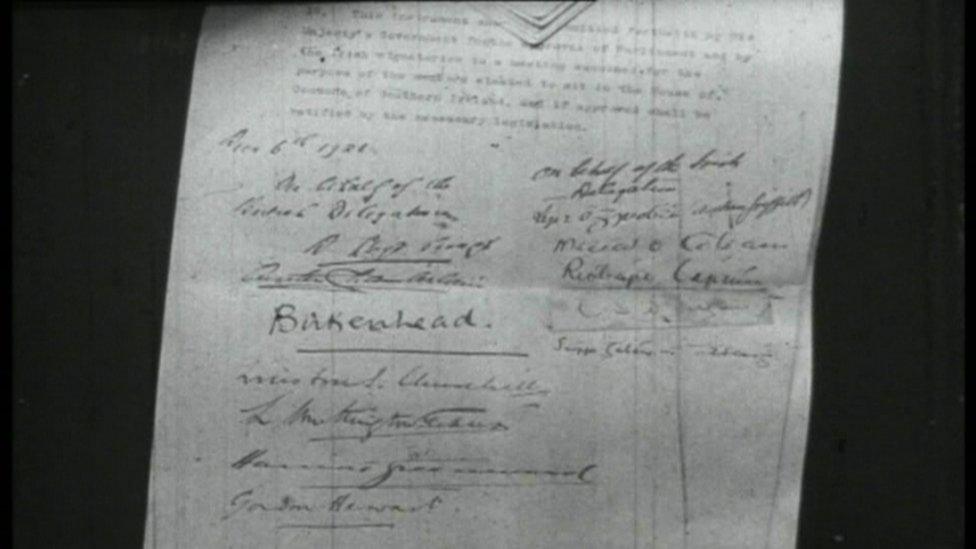

Signatures on the Anglo-Irish Treaty

December 1921: Anglo-Irish Treaty and beyond

The October conference leads to weeks of talks between a British delegation, led by Lloyd-George, and an Irish delegation, headed up by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith.

The result is the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed on 6 December 1921. The treaty cements partition and secures an Irish Free State, which will have dominion status within the British empire.

However, the settlement is unacceptable to de Valera, and many nationalists, who are dismayed that the treaty does not provide an Irish republic and believe it secures partition in perpetuity.

Those who advocate for the treaty argue that a proposed Boundary Commission, which would be set up to finalise the Irish border, would diminish Northern Ireland further and make unification inevitable.

Michael Collins (centre), who agreed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, was the commander-in-chief of the Irish National Forces when he was assassinated in 1922

January 1922: Treaty's ratification signals civil war

The Treaty passes in the Dáil by 64 votes to 57, underlining the deep divide in nationalist politics as Sinn Féin and the IRA breaks into pro- and anti-Treaty factions.

A general election in June leads to a majority for the pro-Treaty side but, by the end of the month, civil war had broken out. It would rage for 10 months, with at least 1,500 people losing their lives. Among them, Michael Collins, who was assassinated on 22 August.

December 1922: Irish Free State established

Westminster passes legislation ratifying the establishment of an Irish Free State. As part of the legislation, Northern Ireland would automatically become part of the free state but would have a month - known as the Ulster month - to secede.

A day later, Northern Ireland's secession passes through the House of Commons of Northern Ireland, copper-fastening the existence of the two states.

Related topics

- Published23 March 2016

- Published27 September 2012