NI Climate Bill: Farming dominates debate over Stormont bill

- Published

Northern Ireland's first ever Climate Bill is progressing through the assembly

After a long and detailed debate, Northern Ireland's first ever Climate Bill jumped an important assembly hurdle this week.

Assembly members voted 58 to 29 to send it for detailed scrutiny - the next step in the legislative process.

The bill would commit Northern Ireland to a target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045.

It would have implications right across society, for transport, business, and how we power and heat our homes.

But it was the impact on one sector - farming and agri-food - which dominated much of the debate.

That's not surprising. The industry is a big driver of the Northern Ireland economy.

It's also our biggest emitting sector, responsible for 27% of greenhouse gases.

A report for the Northern Ireland Food and Drink Association this week recorded more than £5bn in annual sales, with around 80% of produce exported.

Assembly members voted 58 to 29 to send it for detailed scrutiny

The industry was reckoned to support 113,000 jobs directly in production and indirectly along the supply lines - many of them in rural communities.

And there are concerns about how all of this will be impacted by our requirement to address climate change and reduce emissions.

Reduction targets

It's not a unique situation. In the Republic of Ireland, equally reliant on agri-food, there's a huge debate taking place about how food and farming contributes to planned emissions reductions.

On both sides of the border it will be challenging and there are several common themes.

Farmers want to be able to bank the carbon sequestration that's already happening on their farms in grassland, hedgerows and trees.

They hope that carbon store can be weighed into the reckoning when setting emissions reductions targets.

So they want an assessment of carbon already stored on farms to give them a baseline.

They also want consideration given to a different accounting mechanism for the main agricultural greenhouse gas - methane - a compound of carbon and hydrogen atoms.

It comes from livestock, which are really good at converting what, for humans, is inedible grass into edible protein.

Methane gas is produced by livestock like cows and sheep

The by-product of digestion is methane, which is burped out by cows and sheep.

It's a potent greenhouse gas, but it's also short-lived.

Net zero target in 2050

Its warming effect is said to last for 10-12 years before it is oxidized back into carbon dioxide, taken in by plants and the whole cycle starts again.

And for that reason, they believe we need to look again at how its warming effect is measured and consider whether a separate target for methane is appropriate.

In the Republic of Ireland, a new climate bill is making its way through the Dáil (Irish parliament).

It sets a net zero target of 2050.

Teagasc, the Irish Agriculture and Food Development Authority, has looked at various ways of addressing agricultural methane.

These include selective breeding to produce livestock, which emit less of it, and changing animal diets to cut production of it.

Scientists in Northern Ireland's equivalent body the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) are doing similar work.

They are looking at whether the inclusion of seaweed and clovers in animal feeds can help.

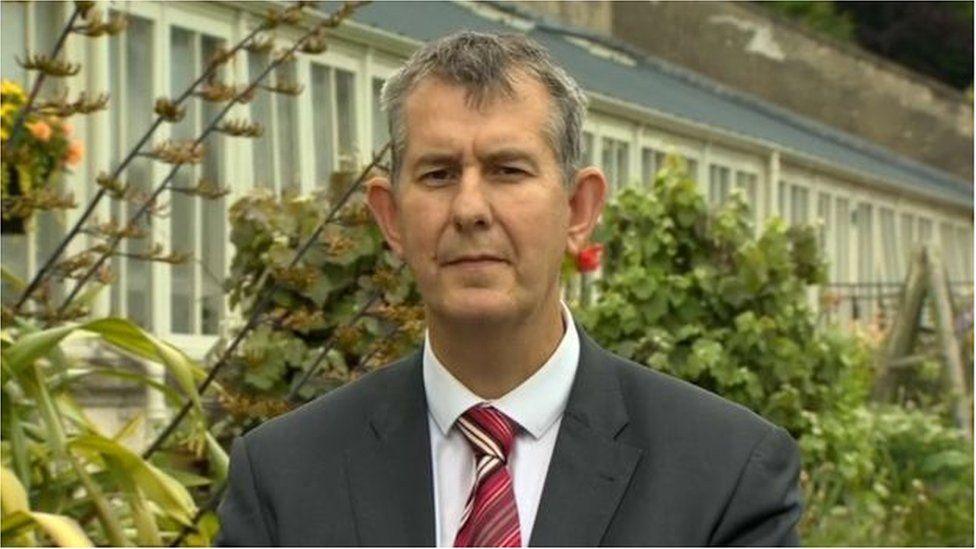

Agriculture Minister Edwin Poots said the bill will disproportionately affect hill farmers

The UK's advisory body to the government on climate - the Committee on Climate Change - has said it sees no credible path for Northern Ireland to reach net zero by 2050, because of our importance as a food producing region.

It said a reduction of at least 82% by 2050 would be a fair contribution by Northern Ireland to the wider UK net zero target; that other parts of the UK should take up the slack; and that it might be necessary to set a tougher target if climate science dictates or technology allows.

It also suggests that even a 50% reduction in meat and dairy production in Northern Ireland wouldn't get us to net zero by 2050.

Farmers say this is proof that the proposed 2045 target in the bill before the assembly is going too far, too fast.

They also point out that if there is a sizeable reduction in agricultural output, without a corresponding reduction in consumption, then we'll end up importing meat and dairy produce from countries like Brazil, where the rainforest is being removed to create farmland.

Cross-party support

There is broad cross-party support for the Stormont bill, though we've seen that start to fray around the edges a bit with several UUP assembly members voting against it, despite their party's endorsement.

Then there's the question of Agriculture Minister Edwin Poots' proposed legislation.

At the moment it appears to be policy proposals, which require executive approval before they can be drafted into a bill.

They have been ready for almost two months now but appear to be stalled, something Mr Poots blames on Sinn Féin.

His legislation was raised at a recent executive meeting, where Mr Poots was asked to provide an assessment of his proposals against the bill currently before the assembly.

Mr Poots said that the bill will disproportionately affect hill farmers, including in the Sperrins and on the Antrim plateau, with production concentrated on better, lower ground.

That's a swipe at parties, including Sinn Féin, who return MLAs from those areas and who back the bill.

Claire Bailey of the Green Party, who is the lead sponsor of the bill, said there was nothing in it that threatened farming.

Clare Bailey said the bill is not a threat to farming in Northern Ireland

She said it wasn't climate action that was the risk but government policy, which she claimed supported intensification and handed power in the supply chain to processors and supermarkets.

She spoke about the fall in the number of farms and farmers in recent decades and suggested there needed to be a rethink to make it attractive and sustainable for new entrants.

The Climate Bill is a big piece of work.

It's probably the most important bit of legislation MLAs will consider in the current mandate and time is tight.

In the coming months we'll see a succession of farm organisations, climate experts and economists give evidence to the scrutiny committee.

That means the debate in the assembly this week was just the start of what will be a long and involved process.

Related topics

- Published31 March 2021

- Published23 March 2021

- Published22 March 2021

- Published28 May 2020

- Published27 March 2021