NI waiting lists: How could the health service get more funding?

- Published

Hospital waiting lists in Northern Ireland are the worst in the UK

Recent figures on waiting lists in Northern Ireland have made for sobering reading.

They revealed that more than 335,000 people are waiting for a first consultant-led appointment.

As a result, Northern Ireland has the worst waiting times of any UK region.

It's a situation that Health Minister Robin Swann said was "undermining" the principle of a free health service.

But how can Stormont find the money to address these problems in the short and long-term?

BBC News NI looks at how the Northern Ireland Executive gets its money and what options it has in trying to get more.

How does the health service - and Stormont - get its money?

The health service in Northern Ireland is funded by the Department of Health, which is given a chunk of the executive's overall budget.

Most of the executive's budget comes from the UK government.

People and businesses in Northern Ireland pay taxes to the UK government, such as income tax, VAT, corporation tax and fuel duty.

The UK government collects this - along with the same taxes from England, Scotland and Wales - and then sends a certain amount back to the devolved governments in Belfast, Cardiff and Edinburgh - known as the block grant.

It calculates this using something called the Barnett formula, which as been around since the late 1970s.

It sets NI's block grant by using the previous year's budget as a starting point and then adjusting it based on increases or decreases in comparable spending per person in England.

So, for example, if spending on healthcare rose by £100m in England, Northern Ireland would get an extra £3.4m in its overall budget because its population is 3.4% the size of England's.

The block grant is then sent to Stormont and it is up to the executive to decide how to spend it.

Gareth Hetherington is director of Ulster University's Economic Policy Centre

Gareth Hetherington, director of the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre, said it was likely the NHS in England would be allocated more money from Westminster in the coming months, meaning there would be more money coming to Northern Ireland.

"Whether that's enough to address the issue of waiting lists here is unknown," he said.

Where else does Stormont get its money from?

Stormont's budget also includes money from regional rates, which are paid by home-owners and businesses. Part of each rates bill goes to councils to fund their services while part goes to Stormont.

It also gets some money from specific agreements with the UK government - for example the DUP's confidence-and-supply deal with the Conservative Party from 2017-2019 or the New Decade, New Approach, external deal which restored devolution in January 2020.

In 2020, the Treasury allocated £687m in Covid-19 funding to Stormont, of which £560m ended up going to the health service.

It also borrows some money - although this is strictly limited.

What is the total amount?

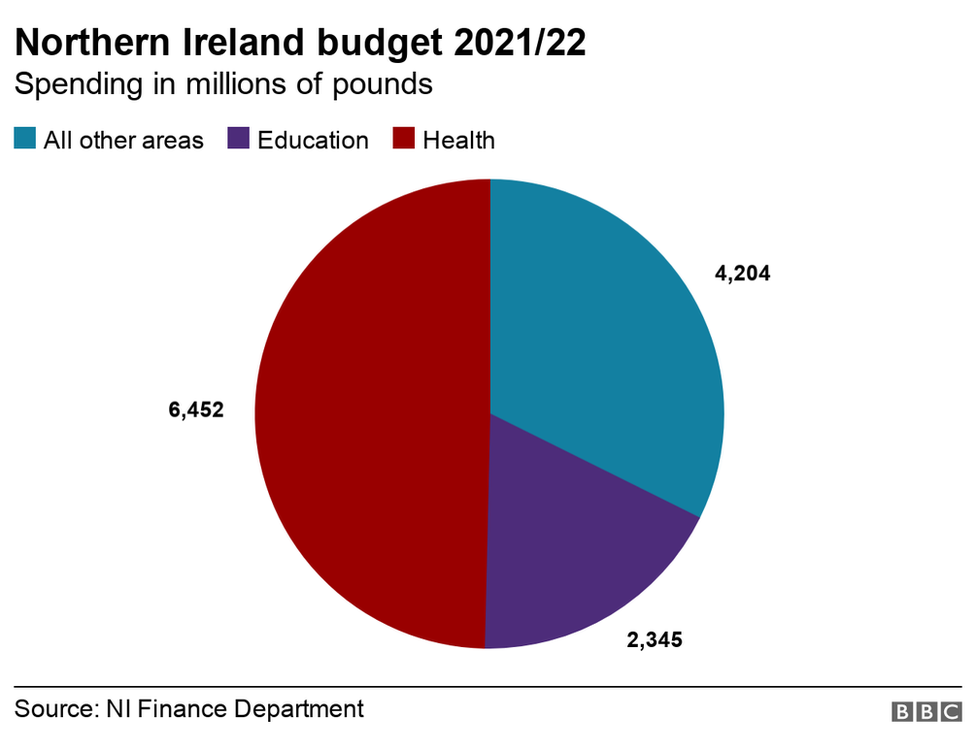

The Northern Ireland budget for 2021-22 consists of £13bn of resource funding and £1.78bn of capital funding. Resource funding is used for things like salaries and running costs while capital funding is for longer-term projects such as new roads or hospitals.

The health department will get almost half of the resource funding - £6.45bn - and a further £326.5m of capital funding.

In Northern Ireland, the health department is also responsible for social care.

How much does NI spend on health per person?

In 2019-20, Northern Ireland's health spending was £2,616 per person, external. That is higher than the UK average, which is £2,445 and also higher than:

England - £2,427

Scotland - £2,507

Wales - £2,546

What about savings?

This would involve making cuts elsewhere in the budget and would mean difficult political decisions.

Finding more money for the health department would mean less money for any or all of the other departments, including education, infrastructure and agriculture.

How could extra money be used to address waiting lists?

Department of Health figures indicate that the amount of money dedicated to tackling waiting lists has fallen since 2014 while the lists have got longer every year.

Between 2014 and 2020, the number of people on waiting lists went from:

127,030 to 308,486 (143% increase) for those in acute and elderly care waiting for a consultant-led appointment

17,209 to 31,700 (84% increase) for in-patient treatment

32,129 to 65,235 (103% increase) for day case patients

Meanwhile, the amount of money spent on waiting lists above core healthcare funded services - what the health department calls waiting list initiative expenditure - has been cut by 62%, from £97m in 2013-14 to £37m in 2019-20.

The department said the drop in cash was fuelling the lengthening waiting lists.

"With public spending under pressure, in-year allocations for waiting list activity reduced. Waiting lists have grown steadily from then," it said.

How could more money be raised?

Regional rates could be raised - this would mean householders and businesses paying more. In the current budget the executive committed to freezing rates.

The total raised by rates for Stormont in the 2021-22 financial year will be £580m.

This means even if every rates bill was doubled, it would only generate another £580m for the health service - less than 10% of its current budget.

Ministers could also ask the UK government for more money.

Stormont also has the power to raise or lower corporation tax but it has never used this since it was devolved in 2015.

If it lowered the rate, then it would need to make up for the shortfall in tax revenue by handing back some of the block grant from the UK government.

Stormont does not have the ability to raise or lower the rate of income tax.

What about other charges?

Another potential, longer-term route politicians in Northern Ireland could take would be the introduction of water charges, which already exist in the rest of the UK, or prescription charges, which are applied in England but were scrapped in Northern Ireland in 2010, external.

These charges have been suggested previously and have proved politically controversial but Mr Hetherington said that, post Covid-19, the public may be more accepting of them.

"What Covid has done is show that spending is needed on the health services and the improvement of public services in general," he said.

"Pre-Covid, we weren't out clapping for health workers, but now there's greater awareness of the work they've been doing, the risks they've faced and the challenges going forward.

"If these charges are brought in to address waiting lists they might be more acceptable to the wider public."

Could Stormont be given tax-raising powers?

The Scottish Parliament is the only one of the devolved legislatures to have the power to change income tax rates.

As well as the power to vary the rate of corporation tax, the Northern Ireland Assembly was given the power to change the rate of air passenger duty (APD) on long-haul flights in 2012.

However, it then emerged it was sending more than £2m to the Treasury every year to cover the cost of subsidising an air route that no longer exists.

In March, it was announced that a commission to examine the possibility of giving Stormont more taxation powers would be led by economist Paul Johnson.

He is the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a high-profile think tank.

Meanwhile, there could be a trend towards higher taxes, not just in the UK but across western, developed economies, according to Gareth Hetherington.

"Public attitude has changed. If we look back to 2010, the Liberal-Conservative coalition sold a message of austerity," he said.

"Fast forward to 2019, there is a limited appetite for austerity.

"2020 is an inflection point, with government spending likely going up in the next decade and taxes going up too."

Related topics

- Published27 May 2021

- Published25 May 2021

- Published19 May 2021

- Published1 April 2021

- Published13 January 2020