NI 100: Gerry Adams and Lord Empey look ahead

- Published

A united Ireland in 20 years' time or Northern Ireland in its current state in 100 years' time?

Two veterans of the political landscape have been offering contrasting views on our future.

The former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams said he thought there could be a united Ireland within the next 20 years.

The former Ulster Unionist leader Lord Empey says he believes Northern Ireland will still exist in a century's time.

Both men were speaking to the BBC about the centenary of Northern Ireland and the partition of the island of Ireland in 1921.

Mr Adams, 72, was asked whether he would see a united Ireland if he lived to be 90.

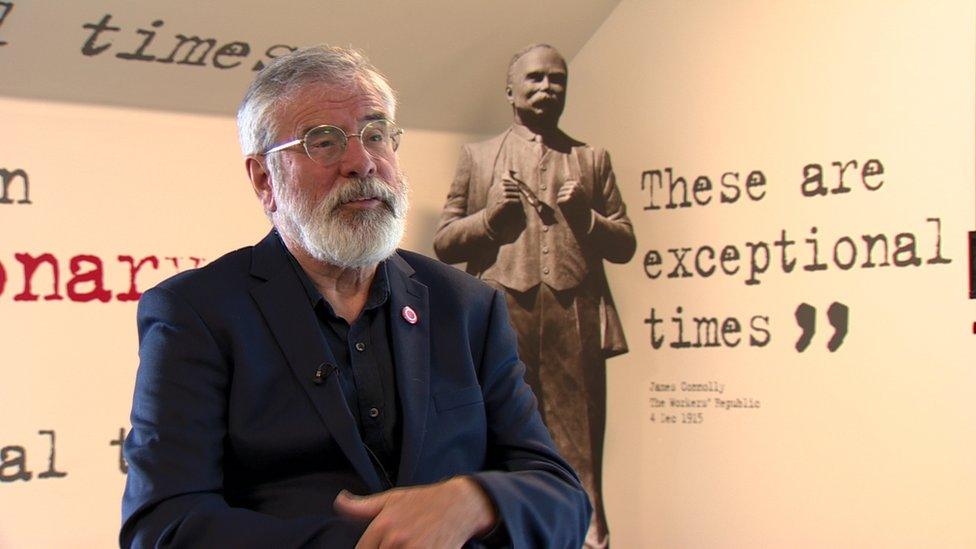

Gerry Adams spoke to BBC News NI at the James Connolly visitor centre

"I would like to think so," he replied.

"I certainly think our children and our grandchildren will grow old in a united Ireland.

"There will be a referendum. The challenge will be to win that referendum."

However, Lord Empey said he was convinced Northern Ireland would still exist in 100 years' time.

"I don't see what the dynamic is that's going to change that," he said.

"The (Irish) Republic's doing very well, it's homogenous, people are working well together.

"You inject into that the sort of disputes we have in this place. To say nothing of the costs, I think it would destabilise the Republic and that would not be in their long-term interests."

Lord Empey was leader of the Ulster Unionist Party from 2005 to 2010 and remains a party officer

Lord Empey was leader of the Ulster Unionist Party from 2005 to 2010. He remains a party officer.

The Ulster Unionists were in power throughout the first 50 years of Northern Ireland and Lord Empey admits it was, "in part, a cold house" for non-unionists.

However, he said nothing could justify the 25 years of violence when the Troubles broke out in the late 1960s.

Asked if he felt the centenary of Northern Ireland was something to celebrate, he said: "It's something that I commemorate and I think we're entitled to do that because Northern Ireland has faced enormous challenges in its 100-year history.

"However, it has to be said, partition was never the Ulster Unionist Party's objective.

"We wanted to see all of Ireland within the United Kingdom. It was only because republicans forced the issue that partition actually occurred which is something that is frequently overlooked."

It was put to him that it could be argued that Unionists forced the issue with the formation of the Ulster Volunteers and the importation of guns.

Lord Empey said: "Bear in mind the atmosphere on the island of Ireland at that particular time. If you even go to 1913-1914, the women's movement who were trying to get equality and votes, they actually were involved in violence.

"The difference between being in the United Kingdom and being in a separate Irish Republic was huge in those days

"The ultimate objective for unionism in 1921 was to see all of Ireland as part of the UK with no border."

Asked if he accepted that a 'Protestant Northern Ireland for a Protestant people' was created, he said: "David Trimble put it very well a number of years ago (when he said) it was, in part, a cold house for people who didn't share the vision of unionism and I think that is undoubtedly true."

He added: "What emerged in the late 60s and into the 70s when the troubles really kicked off, and all of the terrible damage and butchery that took place, was entirely unnecessary.

"Because, while people may have had genuine complaints about some way they were treated, nothing, nothing justified what happened."

Lord Empey acknowledged people not from a unionist tradition "may have had genuine complaints about some way they were treated" in Northern Ireland.

But he stressed that this could not justify the Troubles.

'Fundamental mistakes'

Mr Adams was president of Sinn Féin for 35 years and stepped down from elected politics last year.

He was asked whether, if he had been a republican leader 100 years ago, he would have done anything differently.

He said it was difficult to judge events in hindsight, but he believed "fundamental mistakes" were made.

In December 1921, negotiations between the British government and Sinn Féin concluded with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which set up the Irish Free State.

Gerry Adams said people from his community suffered discrimination in Northern Ireland

However, there was a republican split when the then Sinn Féin leader Éamon de Valera rejected the treaty which had been signed in London by his party colleagues Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith.

"For the republican negotiating team to be allowed, and to allow themselves, to become divorced from their peer group, from their leadership, from the rest of the organisation, I think was fatal and really quite incomprehensible," Mr Adams said.

"They didn't have powers of plenipotentiary but yet they signed up for a treaty and Collins famously acknowledged he was signing his own death warrant.

"Was it ego? Was it underdeveloped politics? Was it maybe a rush to the head… (because) they had actually brought the biggest empire in the world to the negotiating table?

"I don't know. All these things may have played a part in it."

Mr Adams said a united Ireland would be "really invigorated by the input of the northern Protestants".

Asked if that meant a role for Stormont and possible changes to the Irish flag and anthem, he said: "I think all of that's up for discussion, for negotiation."

Arthur Griffith (far left) and Michael Collins (seated middle) at the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Mr Adams said: "The success of the British, once they set themselves on the military course away back in 1916, was that they robbed the revolution of its leadership. They executed the leadership.

"It was an actual attempt to stop a revolution, and they succeeded. The 26-county state became part of the counter revolution.

"So those who used to govern us - mostly Englishmen - were replaced by conservative Irishmen, and they were then in hock with the hierarchy of the Church".

Republican and nationalist MPs refused to take their seats in the new Northern Ireland parliament which first met at Belfast City Hall in June 1921.

Only unionists were involved in the shaping of Northern Ireland.

Mr Adams dismissed the suggestion that nationalists should have become involved.

His view is that the partition of the island was to satisfy British, rather than Irish, interests.

"This is a place that I was born into that didn't want me, that imprisoned me without trial, that discriminated against the people who came from the general community that I came from," he said.

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

Some of the highlights include:

Year '21: You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created 100 years ago by listening to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch-up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published13 June 2021

- Published20 April 2021

- Published21 December 2020