NI 100: Tracing the history of the 100-year-old Irish border

- Published

NI police, including members of the Ulster Special Constabulary, guarding a road near the Fermanagh/Cavan border (circa 1920s)

On May 3 1921, Northern Ireland officially came into existence as the partition of the island of Ireland took legal effect.

The decision to split Ireland in two followed decades of turmoil between nationalists, who wanted independence from British rule, and unionists, who wanted to remain in the United Kingdom.

The border divided the 32-county island into two separate jurisdictions - six counties in the north-east became Northern Ireland, which is still part of the UK.

The other 26-county territory became the Irish Free State, but is now the Republic of Ireland.

As Northern Ireland marks its centenary, BBC News NI looks back at the earliest days of the Irish border and how its controversial 310-mile (500km) route was decided.

Why did partition happen?

The ruins of Dublin's GPO after the 1916 Easter Rising, a failed rebellion that led to war

Partition was viewed by the British government as a compromise solution.

Nationalists had campaigned for "Home Rule" for decades, seeking a devolved parliament in Dublin.

But unionists, who were mainly Protestant, did not want to be ruled from Dublin.

Unionists held a majority in the province of Ulster in the north-east, but in Ireland as a whole they were greatly outnumbered by nationalists, who were mainly Catholic.

In 1916, when Britain was distracted by World War One, it was caught off guard in Ireland when nationalists staged a brief but violent rebellion - the Easter Rising.

The insurrection was defeated within days, but Britain's execution of many of the rebel leaders drew sympathy and support for the nationalist cause.

The Easter Rising is widely viewed as the catalyst for the later Irish War of Independence, which began in 1919.

The following year, the British government decided to partition Ireland, offering nationalists a parliament in Dublin and giving Ulster unionists their own parliament in Belfast.

Why was the border drawn where it was?

Northern Ireland consists of six counties in the north east of the island of Ireland

The province of Ulster consists of nine counties, but only six of them were included within the legal boundary of Northern Ireland.

That was because unionist leaders were worried about nationalist opposition to partition and believed they needed a built-in majority to stay in power.

The Ulster Unionist Council came to accept that would mean sacrificing counties Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan, which each had Catholic majorities, most of whom traditionally voted for nationalists.

Sir James Craig was Northern Ireland's first prime minister, a post he held for almost 20 years

The 1920 Government of Ireland Act had paved the way for Sir James Craig to lead a new unionist-controlled parliament in Belfast and he was elected as Northern Ireland's first prime minister.

Crucially, the Act delineated the border, stating: "Northern Ireland shall consist of the parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry."

The same Act also legislated for a separate parliament in Dublin, but by that stage, British-sanctioned Home Rule was no longer enough for Ireland's revolutionary leaders.

By early 1919, they had set up their own parliament and were fighting a war for full independence.

The first Dáil Éireann (Irish Parliament) met in defiance of British rule during the Irish War of Independence (photo 1921)

How did people feel about the border?

Nationalists, north and south of the border, were infuriated by partition and continued to campaign for independence for the whole island.

Many unionists were also bitterly disappointed, especially those who lived on the southern side and woke up to a very uncertain future on 3 May 1921.

Craig's six-county compromise infuriated many of his unionist supporters, according to historian Cormac Moore.

"The unionists and Protestants of counties Monaghan, Cavan and Donegal were disgusted with the decision of the Ulster Unionist Council to abandon them, as they saw it, and many left the Ulster Unionist Council as a result."

Was the border frontier permanently fixed?

No. When the border was first imposed, it was not clear how long it would stay in place, or if its position would shift in the favour of unionists or nationalists.

In fact, six months after partition, the route the Irish border had taken was put up for negotiation.

That negotiation took the form of the Boundary Commission, a three-man panel, appointed to review the borderline and decide if it was in the appropriate place.

The Boundary Commissioners Joseph Fisher (NI); Richard Feetham (chairman) and Eoin MacNeill (Free State) during a meeting in Armagh in 1924

Of course, for nationalists there was no acceptable border anywhere in Ireland, but some Irish leaders saw opportunity in the commission to gain more territory for the Irish Free State.

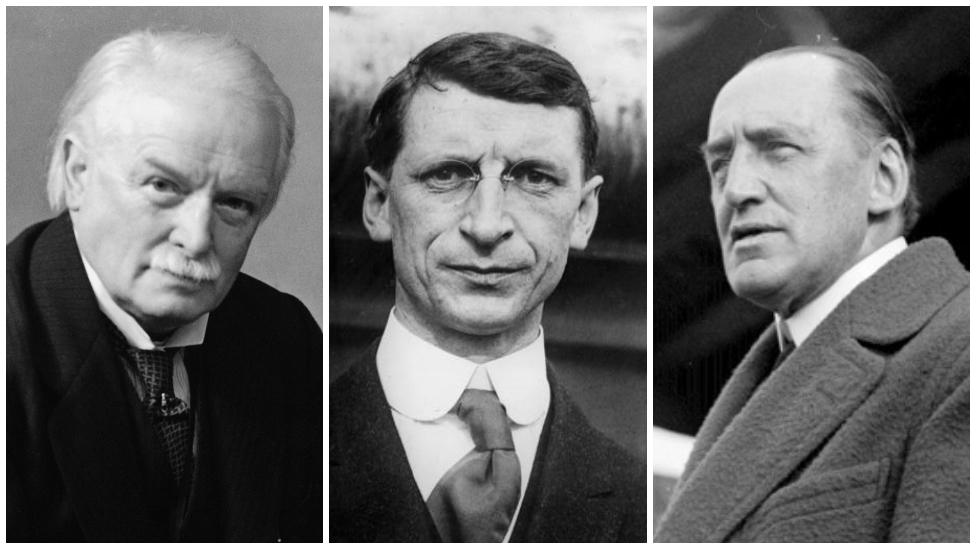

The Boundary Commission was the product of a peace treaty that ended the Irish War of Independence in 1921.

Arthur Griffith (far left) and Michael Collins (seated middle) at the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London on 6 December 1921

Article 12 of the treaty provided for a Boundary Commission to review the existing frontier.

The Irish delegation "naively believed this was going to lead to huge chunks of land coming over to the Free State," says Cormac Moore.

Why did changes to the border not happen?

The appointment of the Boundary Commission was delayed until 1924, partly due to outbreak of the the Irish Civil War.

That three-year delay had consequences for nationalism - it allowed time for the existing border to bed in and the two economies began to diverge.

But the action that "cemented partition" according to Cormac Moore, was the decision by the Free State government to erect customs posts along the border in 1923.

He argues that this led to "a more tangible partition".

"It affected people more on a day-to-day basis than anything that had happened previously to it, and yes, it did solidify the border in many respects."

A truck returning from Northern Ireland is stopped at the border by Irish Free State customs officers (1925)

The three-man commission was supposed to have a British chair, Richard Feetham, and one appointee each from Belfast and Dublin's governments.

But Belfast refused to nominate its commissioner, so the British government appointed a prominent unionist to represent Northern Ireland's interests.

How did Boundary Commission make its decisions?

The panel toured border areas and consulted residents, but several historians agree the ambiguous wording of the Anglo-Irish Treaty allowed its British chairman to interpret his task however he saw fit.

Article 12 of the treaty states the commission "shall determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions, the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland".

Nationalists believed "wishes of the inhabitants" meant at the very least, mainly nationalist areas along the border would transfer to the Free State, according to political geographer Kieran Rankin.

He adds unionists "preferred to concentrate on the qualifying phrase 'in accordance with economic and geographic conditions'" in the belief this would help keep Northern Ireland largely intact.

The commission clearly favoured economic factors, especially when considering large towns with nationalist majorities, such as Newry, County Down.

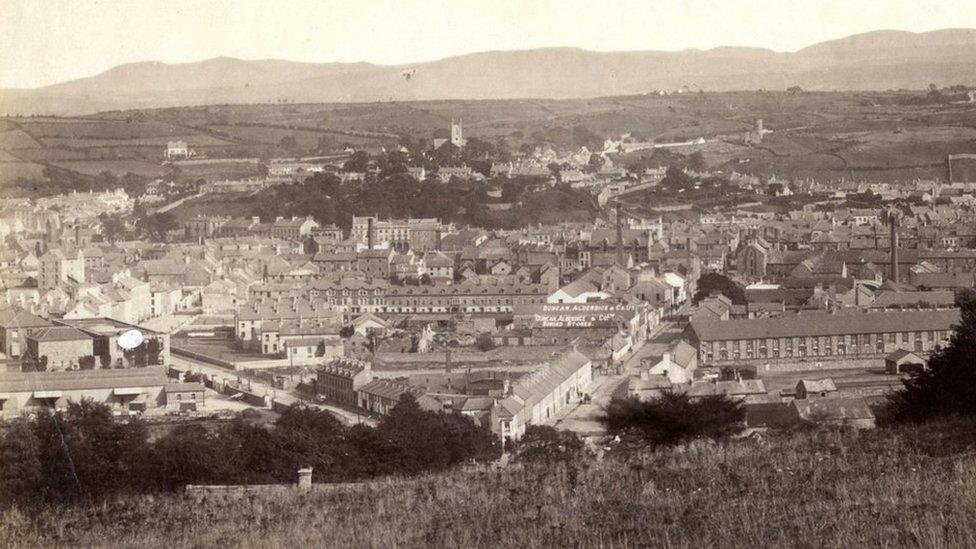

Newry was an important port town in the early part of the 20th Century (photo circa 1900-1910)

Newry was then a significant town for trade and transport, and "approximately three-quarters of its population was reported to be in favour of transfer to the Free State," according to Rankin.

The commission considered Newry's port revenues, coal supply infrastructure, and decided the town was too important to Northern Ireland's linen industry to transfer south.

"This was the archetypal case study of economic and geographic conditions overriding the wishes of the inhabitants," Rankin argues.

Only a small number of border villages, including Crossmaglen, Forkhill and Jonesborough in County Armagh, were recommended for transfer to the Free State.

But none of the larger towns made the transfer list, dashing hopes of Catholic majorities in places like Strabane, County Tyrone.

What was reaction to Boundary Commission proposals?

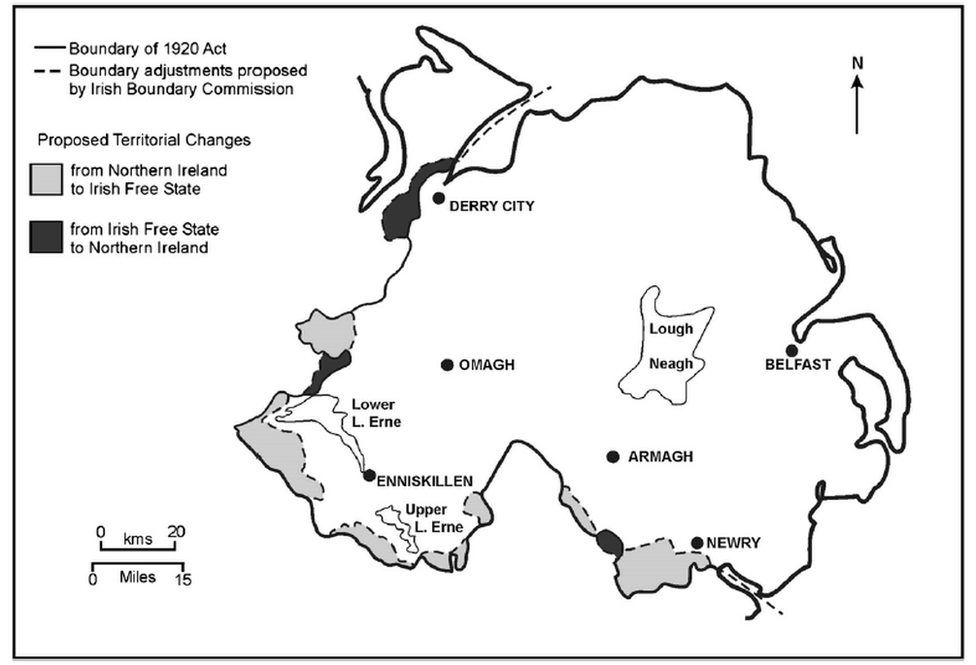

Redrawn map illustrating Boundary Commission proposals for a redrawn Irish border in 1925

Under the Boundary Commission's actual recommendations, the Free State would have gained 282 square miles of territory.

But it would also surrender 78 square miles to Northern Ireland, mainly around east Donegal.

Unionists welcomed the outcome, but the Irish government was horrified.

Under a new boundary agreement signed in December 1925, the three governments agreed to revoke the commission's powers and keep the border exactly where it was.

The commission's report was shelved and was not made public until 1969.

What is the position of the border today?

The once heavily-fortified frontier is now an open border - in many places it is only visible because of the change in road markings

A century after the boundary of Northern Ireland was defined in the Government of Ireland Act, the route of the border remains unchanged.

However, the area around the border has seen many changes.

In the later part of the 20th century, it became a heavily-militarised zone during the Troubles in Northern Ireland

During more than 30 years of violence, the border became studded with British Army checkpoints and was the scene of regular IRA attacks.

In 1993, customs posts were removed as the European Single Market came into effect.

After the 1998 Good Friday Agreement Army checkpoints were gradually dismantled, with the last military watchtowers coming down in 2006, external.

An Army watchtower overlooking Camlough, County Armagh, was among the last to be dismantled

When the UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020, the Irish border became the UK's only land border with the EU.

In order to avoid re-imposing a "hard border" with customs posts on the island of Ireland, the British government agreed to the Irish Sea border instead.

The Brexit debate has galvanised nationalist calls for a referendum on the reunification of Ireland - but the power to call a border poll rests with the UK's secretary of state for Northern Ireland.

Unionists oppose any such move and Prime Minister Boris Johnson said he could not see any Northern Ireland secretary considering a border poll for a "very, very long time to come".

The Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister), Micheál Martin, is also opposed to a border poll in the immediate future, saying it would be "far too divisive" at this stage in the peace process.

As things stand, opinion polls do not suggest that a majority of people in Northern Ireland support the removal of the border that came into being a century ago.

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

Year '21: You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created a hundred years ago in the company of Tara Mills and Declan Harvey.

Listen to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch-up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published11 February 2021

- Published21 December 2020

- Published21 December 2020

- Published21 December 2020