NI 100: How NI devolution changed the face of the UK

- Published

A century after the first devolved parliament, Cardiff, Belfast and Edinburgh have all been given some powers from Westminster

Over the past 22 years, devolution to Belfast, Cardiff and Edinburgh has changed the face of the UK's constitution and created both new opportunities and controversies across the political landscape.

But long before the modern devolved parliaments were set up in 1999 an experiment began in Northern Ireland that continues to have an influence in the present day.

The first ever devolved legislature in the UK was set up in Belfast in 1921 - the Northern Ireland Parliament.

With an upper and a lower house, an executive headed by a prime minister and a governor general representing the monarch, in many ways it resembled the parliaments of the British Empire dominions, which included Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

But it was the first time ever that part of the UK had been given a say over much of its own governance.

There are a lot of differences between the Northern Ireland Parliament and modern devolved legislatures, and not only in terms of its structures.

It became highly controversial as it was seen by many nationalists as a tool to keep the Ulster Unionist Party in power permanently and its government adopted tough security policies in the early years, which were a feature of most of its existence.

It also adopted policies viewed by many as discriminatory against Northern Ireland's Catholic minority.

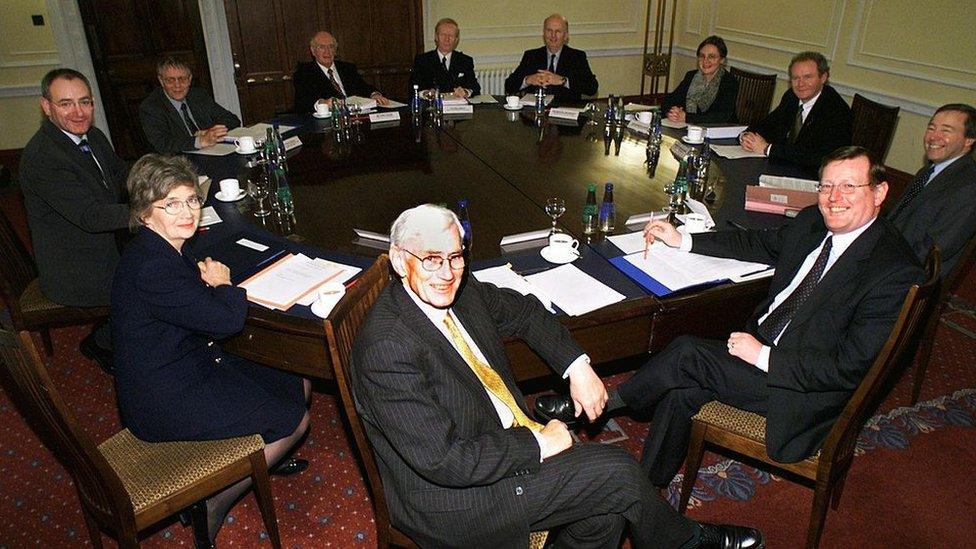

Northern Ireland's modern devolved government first met in December 1999

But one issue which affected the NI Parliament, and which remains highly controversial today, was the so-called West Lothian question.

The term is given to the debate over whether it is fair that MPs from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can vote at Westminster on issues that only affect people in England while their respective devolved legislatures can adopt different policies.

Prof Graham Walker, from Queen's University Belfast, says this issue first really reared its head when Harold Wilson's Labour government came to power at Westminster in 1964 with a majority of just four and he was frustrated that unionist MPs voted with the Conservative Party.

"Harold Wilson raised it in talks with [Ulster Unionist Party leader] Terence O'Neill and Terence O'Neill's argument was that actually Northern Ireland was under-represented, it only had 12 MPs and on the basis of its population it was entitled to more than that," Prof Walker says.

"His argument was there was a bit of a trade-off therefore between NI not getting the number of MPs it was entitled to and at the same time those MPs being allowed to debate and vote on issues pertaining to other parts of the UK.

"Harold Wilson was not really appeased by this, he was very irked.

"Northern Ireland in a sense provided a precedent and it was interesting that when Scotland got devolution in 1999, a few years later its quota of MPs was reduced from 72 to 59."

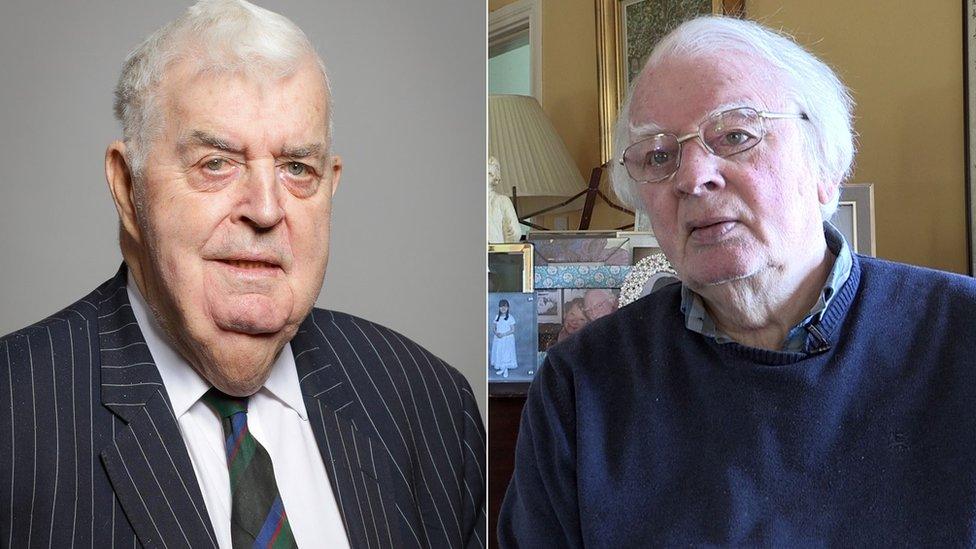

Terence O'Neill (left) and Harold Wilson did not see eye-to-eye on some NI-related issues

Another legacy is the way devolved administrations are funded. Originally Northern Ireland was to be self-sufficient but this soon proved to be impractical.

Prof Walker says that when devolution for Scotland and Wales was first debated seriously in the 1970s there was a lot of discussion about this point, leading to the idea that the devolved parliaments should receive funding from a block grant from Westminster, which remains the case today.

"You could say Northern Ireland's first example of devolution was highly significant in terms of the financial issues which carried through," he says.

The NI Parliament also showed the difficulty of intergovernmental relations between devolved administrations and London, Prof Walker argues, which has carried on to the present.

"The intergovernmental relations have been a very problematic part of devolution over the past 20 or so years. Intergovernmental relations between Northern Ireland, Wales, Scotland and London have been pretty shambolic," he says.

"The system hasn't really worked - some people say because of this, you have what's happened in Scotland where some Scots are losing faith in the union in its entirety.

"If you went back to Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972 there was ample warning there in terms of how the failure to construct effective intergovernmental relations could be very damaging.

"By the time the Troubles erupted in the late 1960s, the British government at the time were clueless. They really had nothing much to go on."

In Prof Walker's view, the lack of intergovernmental relations has fed into a current situation where the various administrations are "making it up as they go along".

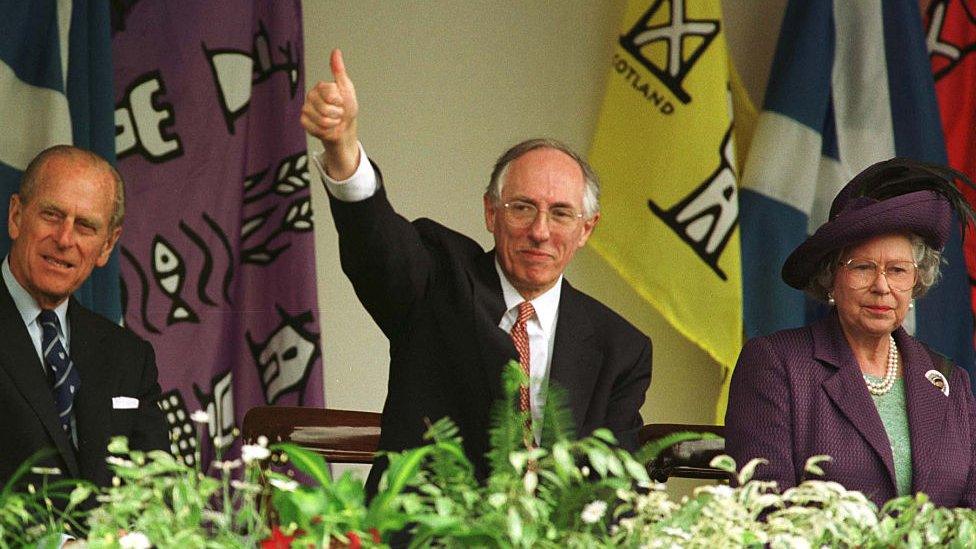

The Queen, pictured with Prince Philip and Scotland's then-First Minister Donald Dewar, opened the modern Scottish Parliament in 1999

The Northern Ireland Parliament does not have much of a reputation for trailblazing. For much of its existence it passed legislation that mirrored what was being passed at Westminster.

But it did also demonstrate how devolution could give an area of the UK the ability to diverge from the London government and tweak policies to suit its own circumstances.

Prof Walker points to the Education Act of 1947 as one of the most important achievements of the parliament.

"You might say that it benefited the Catholic minority most of all in that when you get to the civil rights period [in the 1960s] the leaders of the civil rights movement are the beneficiaries of that act. They have gone on to higher education," he says.

"It really did shake-up the whole education system, it provided new opportunities."

There were new education acts for England and Scotland at this time, but Prof Walker says the Northern Ireland act was "geared towards particular Northern Ireland conditions" taking into account the role of grammar schools and the Catholic sector.

"It was an important piece of legislation in terms of social change, social mobility," Prof Walker says.

"The unionist government deserves credit for that because they had to face down opposition from within their own party who disliked the aspect of the act which increased funding for the Catholic schools.

"This goes against the prevailing narrative of unionist rule because it did not pander to the unionist grassroots and actually did benefit the minority."

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

Year '21: You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created a hundred years ago by listening to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch-up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published24 June 2021

- Published20 June 2021