Corporation tax: Stormont continues to face taxing issues

- Published

It was hoped that by cutting corporation tax Northern Ireland could attract more foreign investment

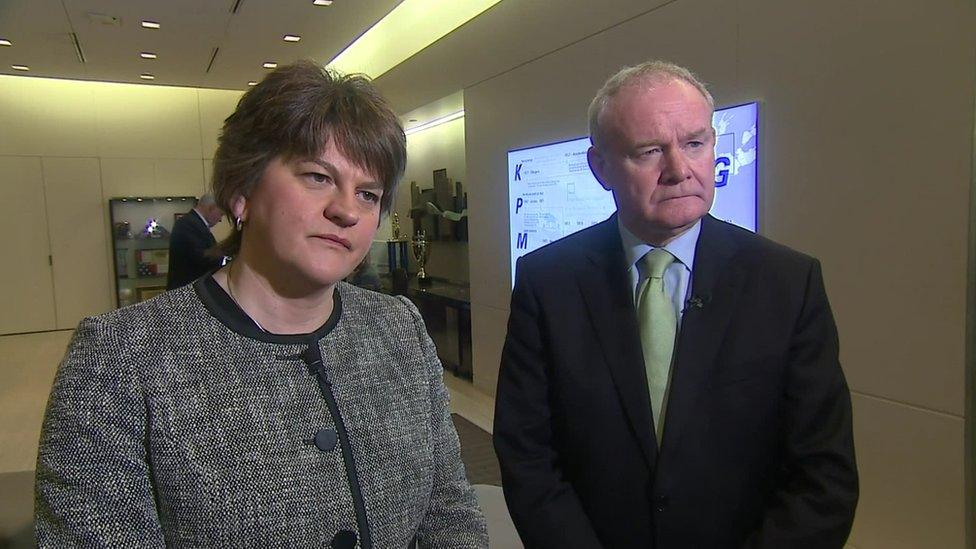

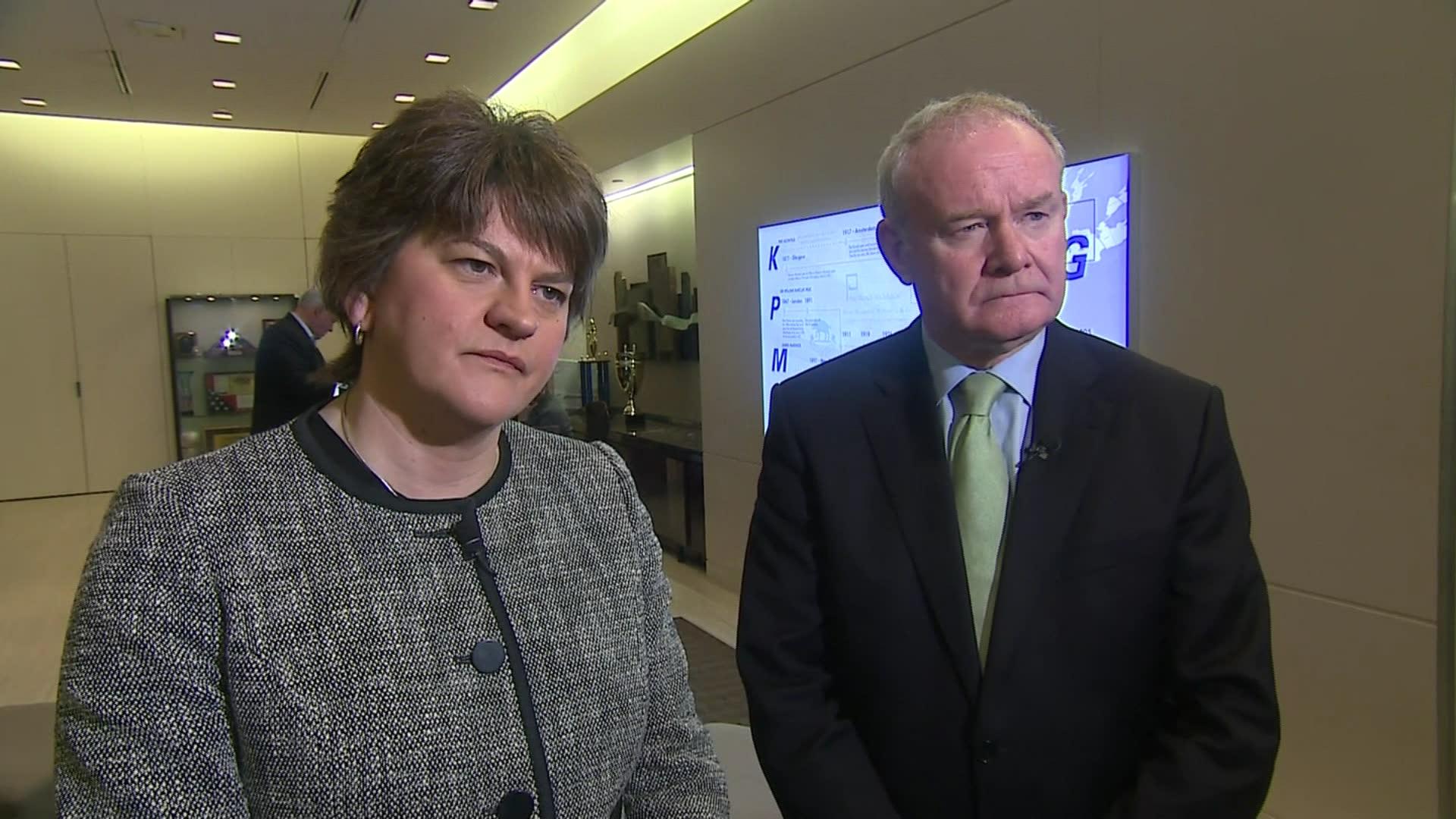

Arlene Foster and Martin McGuinness travelled to the United States with a story to tell in March 2016 .

New York, Washington DC and California businesses heard that Northern Ireland would soon be a low tax location to rival the Republic of Ireland.

The year before a law was passed effectively giving the NI Assembly the power to take control of corporation tax.

It is the tax that companies pay on their profits.

The low corporation tax rate in the Republic of Ireland has been seen as a vital tool to attract investment.

The plan was that Stormont would set a tax rate of 12.5% to match the Irish Republic.

Arlene Foster and Martin McGuinness pictured in New York in 2016

There were still some issues to be ironed out, but the first and deputy first ministers were telling investors to prepare for a new opportunity.

Five years on the power has never been used and the tax rate in Northern Ireland is 19%, the same as the rest of the UK.

The problem is that if you devolve a tax and then cut it you will be sending less money to the UK Treasury.

So in turn the Treasury will cut the block grant - the money it sends to Northern Ireland for public services.

Stormont and the Treasury were never able to agree how big that cut should be and it how should be implemented.

The corporation tax saga was recalled this week as the man leading a review of Stormont's fiscal powers updated an audience at Queens University on his work.

Paul Johnson chairs the Fiscal Commission, an independent body, external set up by the finance minister to take a comprehensive look at what taxes could be devolved.

Northern Ireland is the only one of the devolved regions not to have conducted a review of this sort.

In Wales, the Holtham Commission reported in 2010 and in Scotland the 2014 Smith Commission led to the devolution of some income tax powers.

Stormont has set up a commission to look at what tax raising powers could be devolved

Mr Johnson said the experience with corporation tax should not be seen as a barrier to the devolution of other taxes to Northern Ireland.

"The issues with the block grant and corporation tax are bigger than those for a lot of other taxes," he explained.

"It's particularly difficult to know, for example, how much the rest of the UK might be losing because companies are moving to Northern Ireland if the corporation tax rate is cut.

"We've actually got models for adjustments for income tax, because there are models for Scotland and Wales for doing that.

"So we know there are ways of achieving that which are probably easier than for corporation tax."

He pointed to the experience of Scottish income tax as arguably a successful example of devolution.

It's a local system which takes account of local political preferences by being more "progressive" - which in practice means higher earners pay more than they do in other parts of the UK.

However the additional revenues raised by the Scottish income tax are much lower than forecast which points to the complexity of devolution.

First step on long journey

Mr Johnson said there needs to be a discussion about what further devolution is supposed to achieve.

"One of the things we've really learnt from talking to stakeholders is there's quite an appetite to have a better understanding of tax raising powers, how the system works, what its effect is.

"So as well as providing recommendations to the finance minister, I hope we can generally improve the debate about fiscal powers in Northern Ireland."

The Commission aims to have a report published before next year's Northern Ireland Assembly election which is scheduled for May.

But Mr Johnson said it should not be seen as the last word.

"In Scotland and Wales there was a lot of work done after the first commissions looking at tax devolution and then a long period between those commissions and big changes happening," he added.

"So we see our work as the first step on what might be quite a long journey."

- Published29 September 2021

- Published12 March 2021

- Published14 March 2016

- Published6 March 2021