Brexit: What now for the Northern Ireland Protocol?

- Published

The EU unveiled its plans to ease the impact of the Northern Ireland Protocol this week

There's a cliché that Brussels closes for the summer as EU staff rush for the beach.

But for one group of officials there wasn't much of a break this year.

They had been tasked with combing through the rules of the single market to find creative ways to ease the impact of the Northern Ireland Protocol.

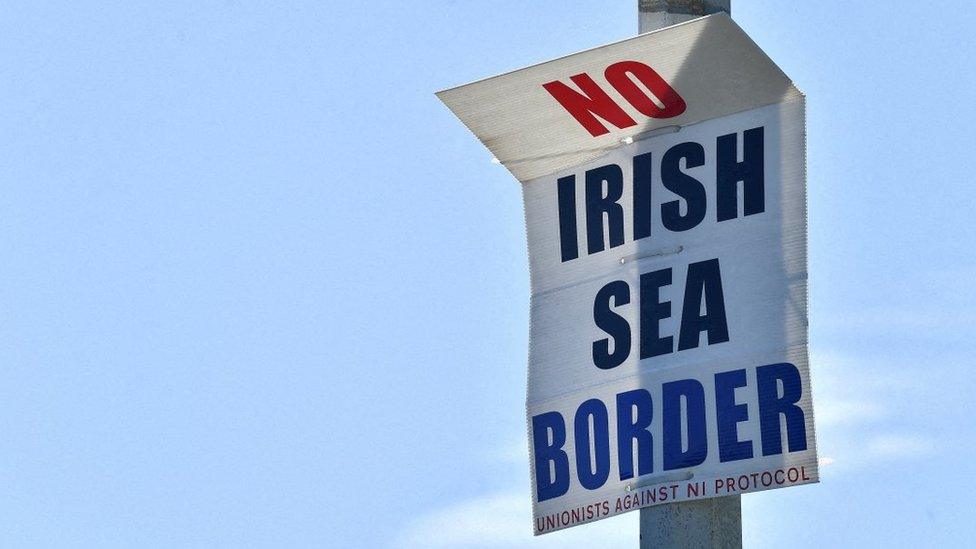

The protocol is the Brexit deal which prevents a hard Irish border by keeping Northern Ireland inside the EU's single market for goods.

That also creates a new trade border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, something the EU accepts is causing difficulties for many businesses.

This week the EU showed the fruits of its work.

"We completely turned our rules upside down and inside out," the European Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič said.

The headlines were eye-catching - an 80% reduction on the checks for GB food products destined for Northern Ireland shops and a 50% cut in customs formalities.

Those figures need to be approached with some caution as they come with caveats and in the case of customs, it's not completely clear how the target will be reached.

But the overall thrust is clear - it should be easier for Northern Ireland businesses to continue importing goods from the rest of the UK.

Products of animal origin - meat, milk, fish and eggs - need a certificate to enter the single market

The proposals for agrifood are the most fully expressed, building on existing "grace periods", which means the EU's rules aren't being fully implemented.

The EU's rules on food imports are based around export health certificates (EHCs).

Live animals and products of animal origin - meat, milk, fish and eggs - need an EHC to enter the single market.

The EHC has to be signed by a vet or other qualified person in the exporting country after they have inspected the goods.

An EHC is needed for every different product line, for example there are different certificates for milk and yogurt rather than a generic dairy certificate.

Currently supermarkets and some other large retailers in NI are being allowed to move lorries full of different food products with just one certificate.

The EU is effectively proposing that arrangement should be made permanent and expanded to cover all retailers.

Madagascan prawns

The EU's second line of defence for food safety is the operation of border control posts (BCPs).

All goods which require EHCs must pass through these facilities where there are three types of checks - on the documents, verification of the identity of the goods and some physical inspection.

The document checks are already an online process but the EU is proposing the identity and physical inspections be reduced far below what is usually required at single-market borders.

This is what the 80% reduction refers to: "An 80% cut compared to what is normally required in EU legislation," a senior official explained this week.

The EU proposal says the level of checks would be part of "an overall system defining the risk management principles and related decisions, as provided for in EU legislation".

Chilled sausages are considered too risky to allow into the single market

This reads like a nod to evidence Northern Ireland's chief vet Robert Huey gave to a parliamentary committee last year.

He said the frequencies of checks laid out in the legislation can be increased or decreased according to local risk assessment.

He hoped that would allow checks on supermarket goods in particular to be "close to zero or perhaps even zero".

The EU seems to be moving in that direction, but with plenty of caveats.

Firstly the light touch only applies to products originating from the UK or EU so, for example, a case of Madagascan prawns coming from a GB supermarket depot wouldn't benefit from reduced checks.

Secondly it only applies to retail goods, not ingredients which are intended for further commercial processing.

The goods will also have to be labelled for UK sale only.

Checks are being carried out on some products at Northern Ireland's ports as a result of the protocol

The EU says it will also be dependent on its long-standing request to get access to real-time information on GB-NI trade flows, an area where Mr Šefčovič says progress is being made.

Finally the EU requires the UK to build properly-equipped and staffed BCPs to replace the temporary facilities which are currently operating.

National identity goods

There is a further layer of complication for what are known as prohibited and restricted (P&R) goods.

These are products which the EU usually considers too risky to allow into the single market, including chilled sausages.

The EU had intended a "grace period" to allow retailers in Northern Ireland to replace their GB sausage suppliers; the UK government had hoped some other arrangement could be worked out.

This eventually blew up into the so-called sausage war for which the EU has now suggested a detente.

Sausages and perhaps some other items could be designated "national identity goods", meaning they have a special resonance in Northern Ireland.

These products could still be sold in Northern Ireland but they would require their own EHCs rather than being covered by the "one certificate per lorry" concept.

The EU proposals also leave open the possibility that P&R products which aren't national identity goods could still be banned though that will be a matter for negotiation.

As a further level of risk control the EU has proposed that "basic production requirements" for those P&R meat products in GB would need to remain aligned with those in the EU.

Theresa May's former Brexit adviser Raoul Ruparel has said a requirement for ongoing alignment with product regulations "is not really a new or novel solution".

He added that it's also not clear if the UK would agree to this arrangement in the longer term.

Related topics

- Published13 October 2021

- Published14 October 2021

- Published15 October 2021

- Published18 September 2021

- Published2 February 2024