Covid-19 rules to ease in NI but what do the figures say?

- Published

Northern Ireland's Covid-19 restrictions are due to ease further next week after decisions made at the executive on Thursday evening.

It is a move which has been criticised as "stupid" and "madness" by the chairman of the British Medical Association (BMA) in Northern Ireland, Dr Tom Black.

Two executive ministers - the SDLP's Nichola Mallon and Naomi Long of the Alliance Party - have both expressed concern about the planned easing.

As ever during the pandemic, numbers and statistics lie at the heart of the argument.

So what do the figures tell us about Northern Ireland's progress in the pandemic at the minute?

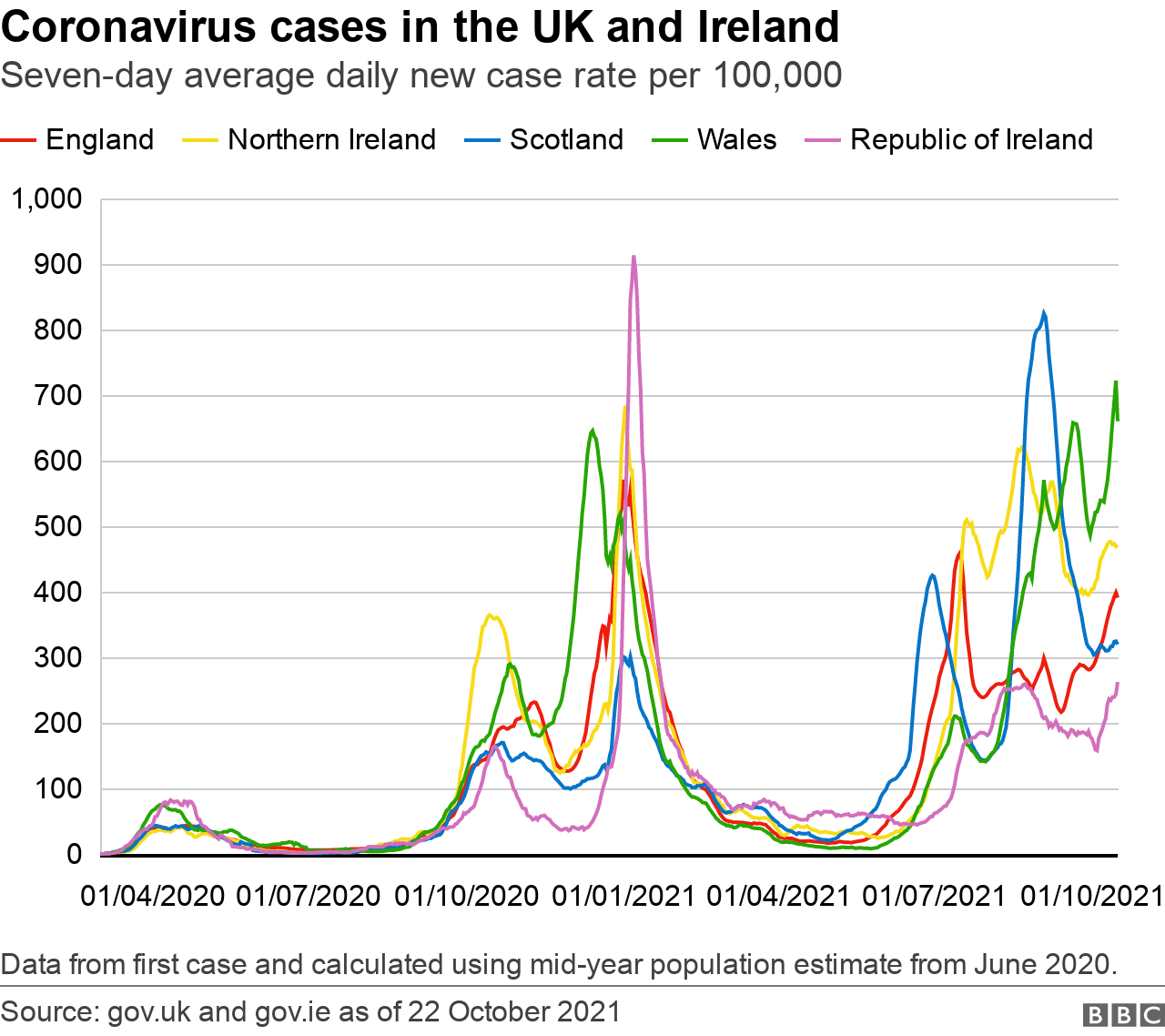

Cases and infection rates

Both of the following statements are true:

Northern Ireland hasn't seen a significant increase in case rates for months

Northern Ireland's case rate is high

That is because Northern Ireland has had an elevated infection rate for more than three months now.

Scotland, Wales, England and the Republic of Ireland have all seen spikes in case numbers at some points over the same period.

Generally, those were sharps rises, swiftly followed by steep falls.

But Northern Ireland has been a bit different in that respect.

Our case numbers started to increase in the middle of July and they have more or less stayed around a similar level since then.

Rather than looking at day-to-day increases and falls in case numbers, it's more useful to look at the seven-day rolling average - that is how many cases we would expect to see each day over the course of a seven-day period.

The reason this is more useful is that it allows us to see trends - the direction of travel, so to speak.

This average rate rose above 1,000 cases per day on 15 July. It hasn't fallen below 1,000 since. That's 99 days with consistently elevated case rates.

To put that in perspective, we saw a similar case rate for 18 days in the winter peak last year between the end of December and the beginning of January.

In short, we have been - and continue to be - in the most prolonged period of high Covid infection that we've seen at any point in the pandemic.

But we've got a vaccine so why this continually high rate of virus spread?

The Delta variant and its increased transmissibility is definitely an issue.

Factors like schools restarting and the gradual easing of restrictions may have played a part but it's difficult to tell from the numbers.

We saw greater increases in cases in mid-August (before schools returned) in comparison to early September.

And case numbers have remained relatively static despite a number of restrictions being eased over the past few months.

A bigger clue lies in the age profile of those getting the virus.

Over the past week, 42% of cases have been in people under the age of 20 - that is people less likely to have been vaccinated; and children who are not eligible for vaccines.

While Northern Ireland has a fairly high infection rate, it isn't the highest in the UK.

Wales - which has a very high vaccination uptake - has a particularly high infection rate right now and it's still rising.

England's infection rate has been rising too and has caught up with Northern Ireland.

The following are the infection rates per 100,000 population for the seven days up until October 17:

England - 466.3

Scotland - 324.2

Wales - 691.5

Northern Ireland - 466.9

Republic of Ireland - 239.8

The Republic of Ireland has had a consistently lower infection rate than Northern Ireland since the middle of June.

However, the case numbers south of the border have been on the rise.

That said, the Republic's infection rate is still just about half that of Northern Ireland's.

In short, Northern Ireland's infection rate is high; has been for three months; and shows no immediate signs of falling.

It's also worth noting that over the course of the pandemic to date, the disease has been more prevalent in Northern Ireland than anywhere else in the UK.

The following are the number of confirmed cases per 100,000 population in the UK since the pandemic began:

England - 13,066

Scotland - 11,350

Wales - 13,119

Northern Ireland - 13,970

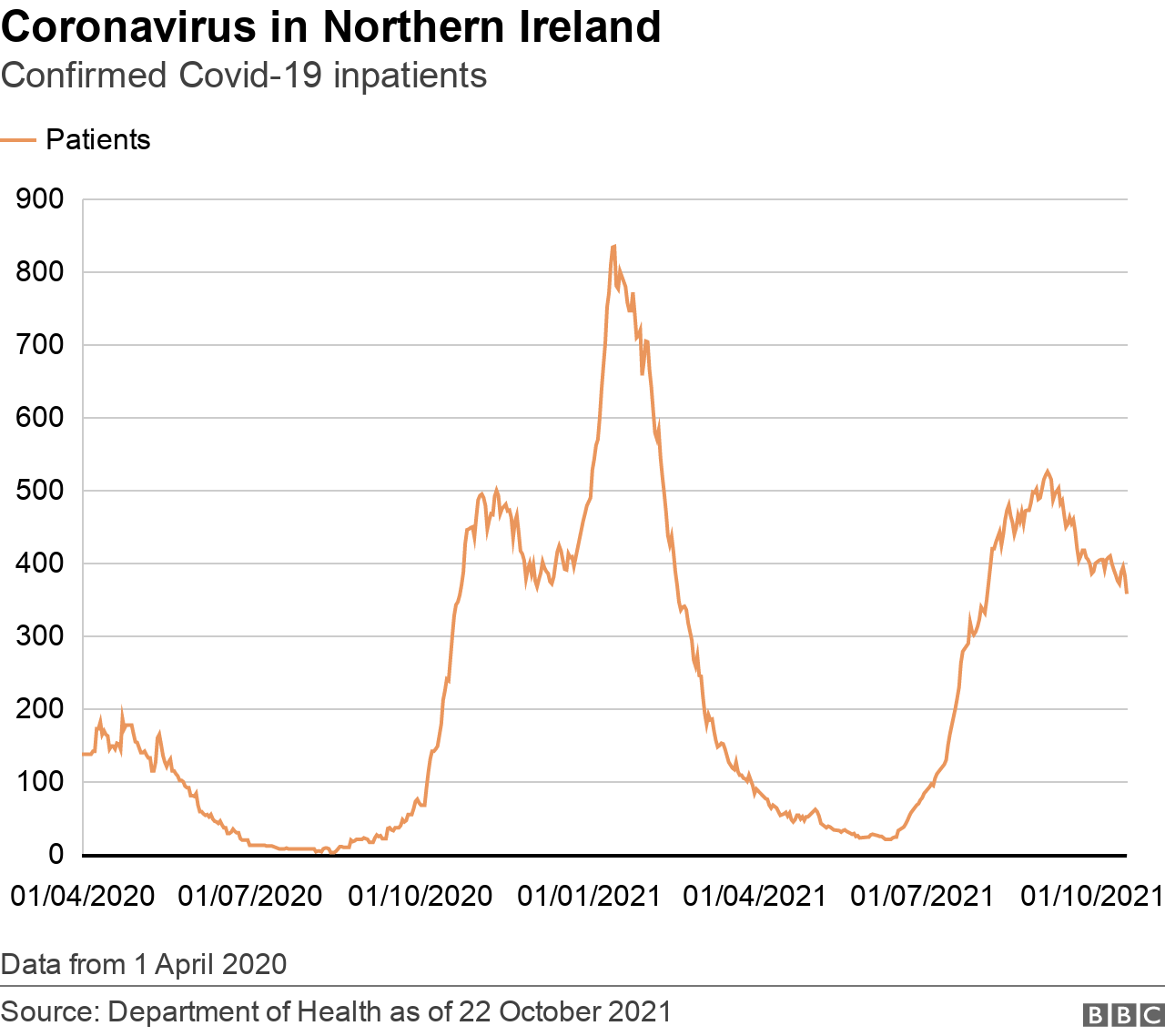

Hospitalisations

The reason any increase in Covid case numbers is a concern is the potential added pressure it can place on our health system.

And there's good news and bad here.

First the good news - the number of patients in our hospitals with Covid-19 has been falling, albeit it very slowly.

The bad news is that the numbers are still reasonably high.

By the latest figures from the Department of Health (DoH), there has been an average of 382 Covid-positive inpatients in Northern Ireland's hospitals each day over the past week.

That is by no means the worst level of hospitalisation we've seen over the course of the pandemic - more than a thousand inpatients were Covid-positive at one point in January.

That said, about 12% of all hospital beds in Northern Ireland have a patient in them suffering from Covid.

And, of course, this added pressure with Covid patients comes in the context of mounting "normal" winter pressures on the health service.

Right now, across Northern Ireland there are about 180 more patients in hospitals than there are beds.

The health system is running over its intended capacity and that has obvious knock-on effects.

The age profile of the patients in hospital with Covid has changed slightly over the past two months or so.

Previously, there had been an increase in the proportion of younger adults in hospital.

That has now receded and most patients with Covid are once again older people - the majority (57.5%) being 70 or older.

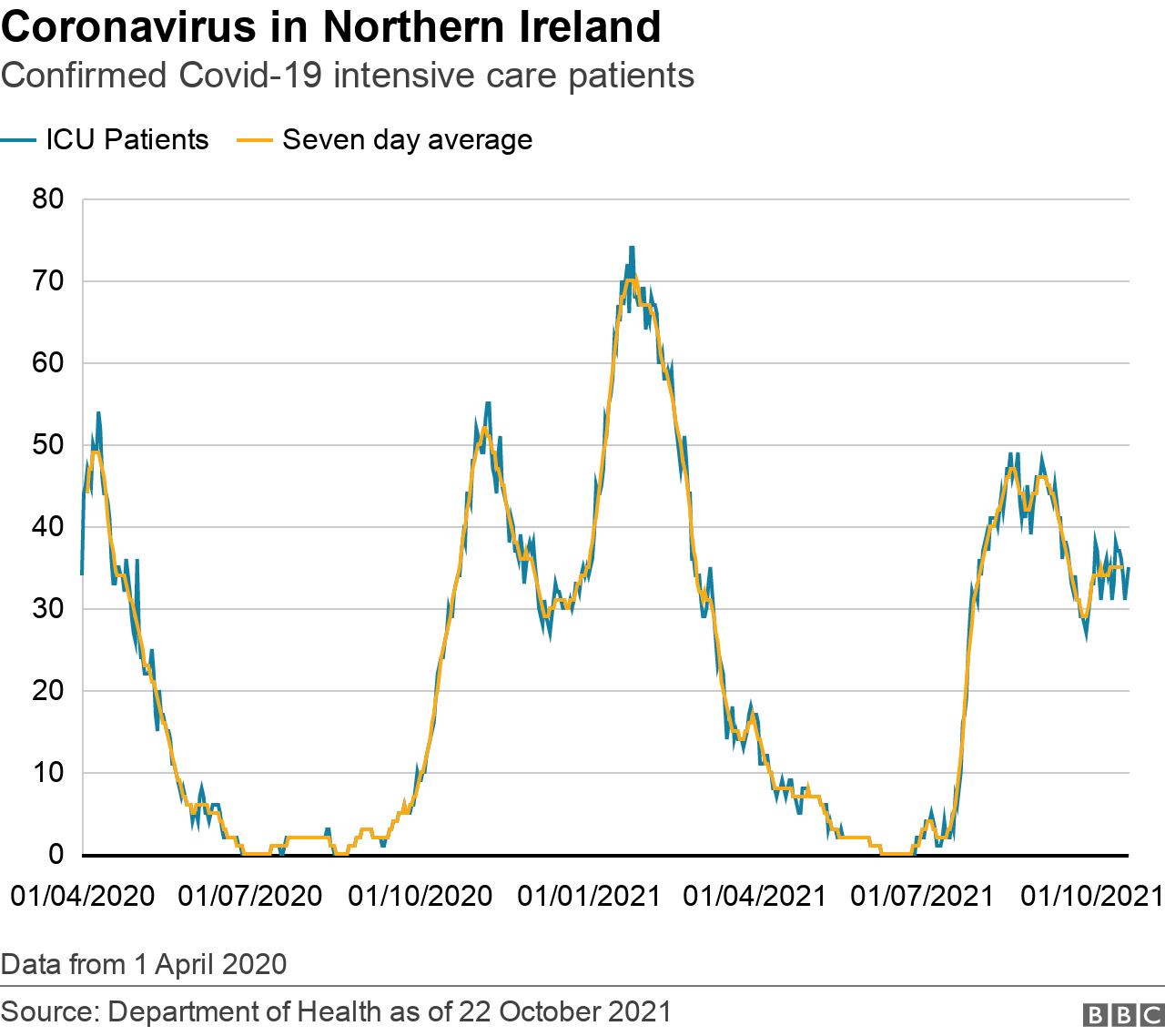

The picture in intensive care units (ICU) is one of consistent pressure due to Covid.

The number of patients in ICU with Covid has been roughly between 30 and 40 for about six weeks.

At the minute, there are 33 Covid-patients requiring intensive care, with 24 of those needing help breathing.

The patient profile of those in ICU over the past few months also tells us something about the virus - the average age is about 51; more ICU Covid patients come from a deprived background; and they're more likely to be overweight.

In fact, medics are starting to see weight as a key factor which goes hand in hand with patients suffering badly from Covid - that is known as comorbidity.

Of the Covid patients admitted into Northern Ireland's ICU wards since May 1 this year, 55% had a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more - meaning they were obese or very obese.

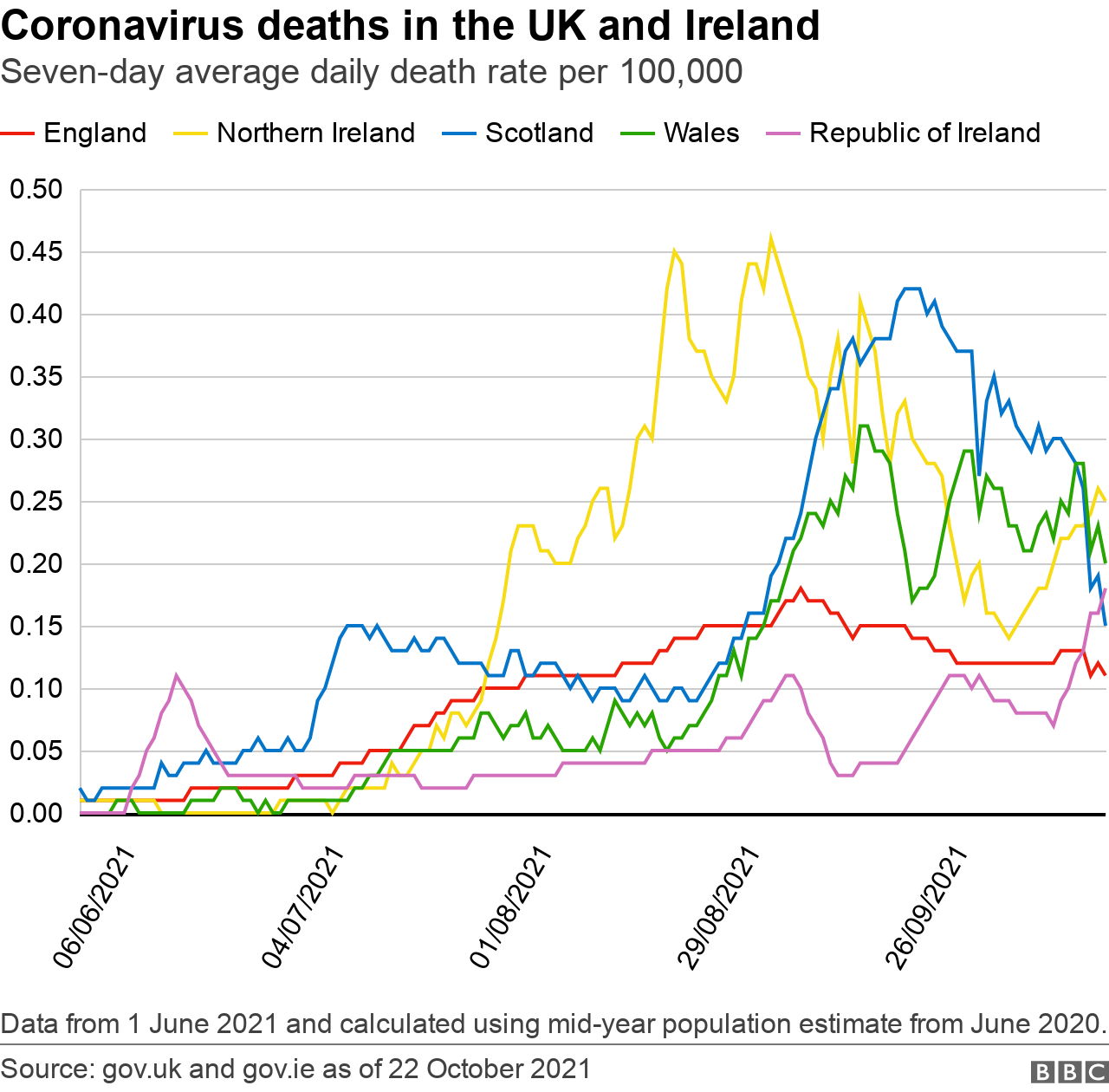

Deaths

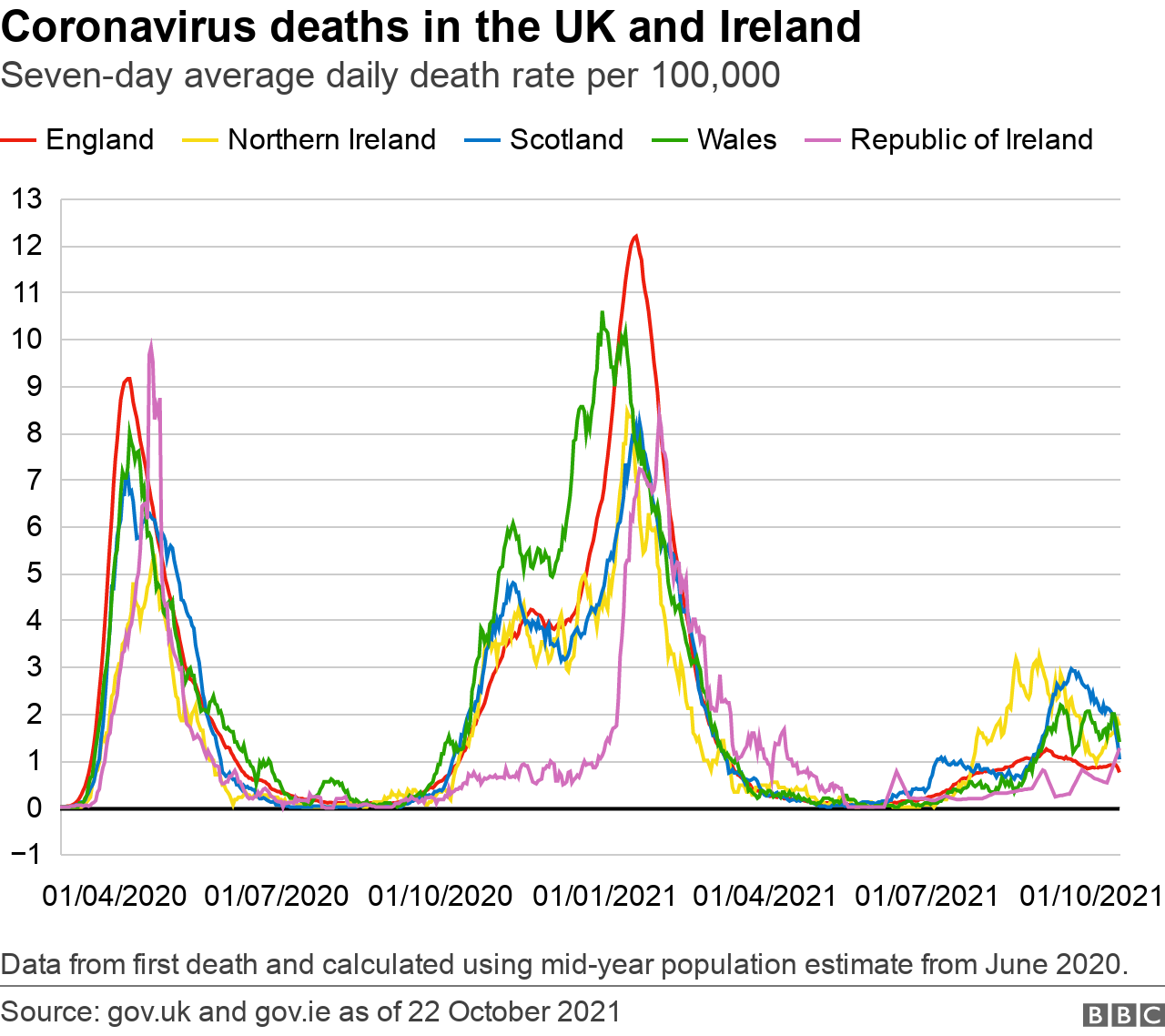

From the end of July until the middle of September, Northern Ireland had the worst Covid death rate in the UK.

That is no longer the case, with Scotland and Wales both having a higher death rate right now.

That said, Northern Ireland's death rate has been increasing over the past two weeks or so.

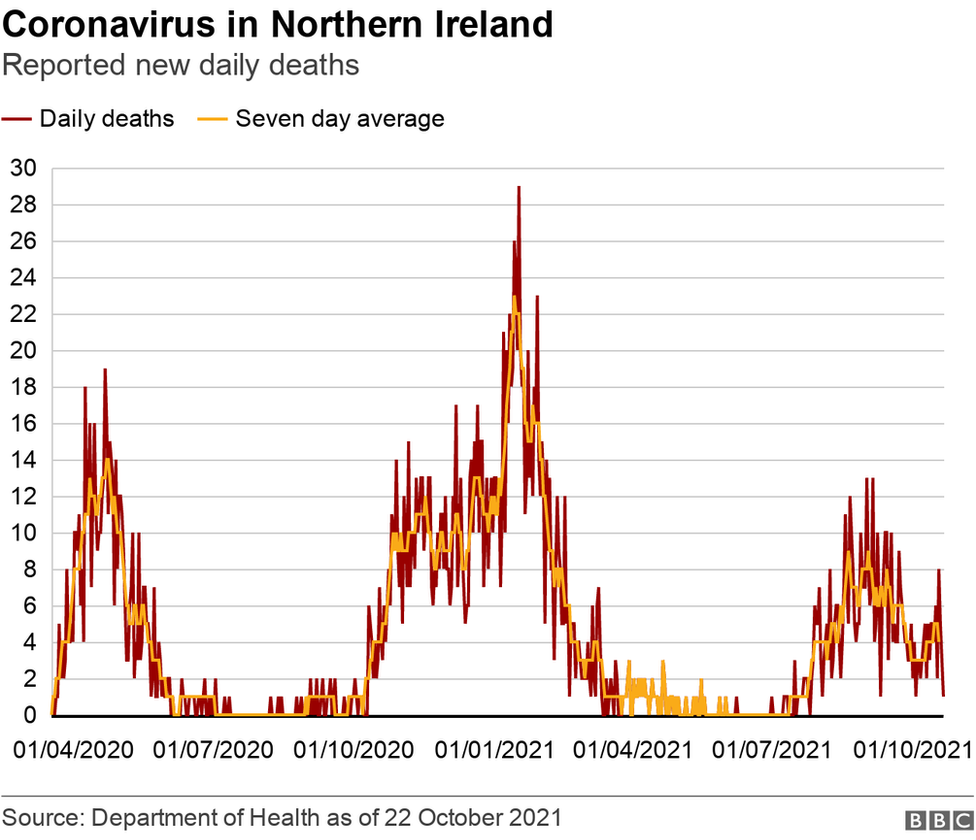

According to DoH figures, there have been 2,646 Covid-related deaths in Northern Ireland since the beginning of the pandemic.

And the current seven-day rolling average for deaths indicates an expected five deaths every day.

The Republic of Ireland's latest seven-day figures indicate seven expected deaths per day - but remember, that's for a population two and a half times the size of Northern Ireland's.

The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (Nisra) recorded 38 related deaths registered in the week up to 15 October, taking the agency's overall total to 3,539.

The reason for the difference of almost a thousand between the DoH and Nisra figures is that the two authorities count deaths differently.

The DoH records deaths within 28 days of a positive test for Covid.

Nisra counts the death certificates on which Covid is mentioned.

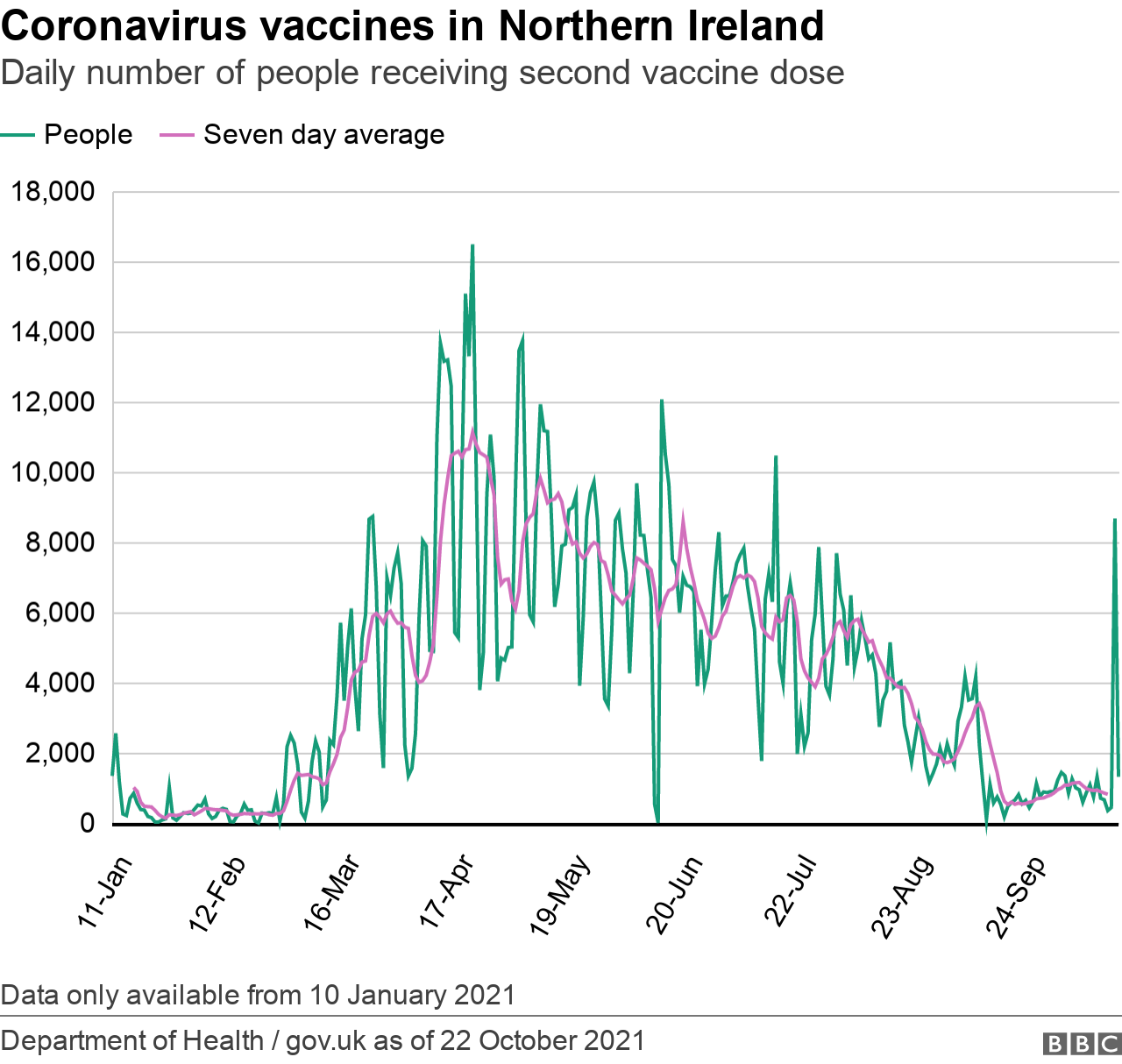

Vaccination

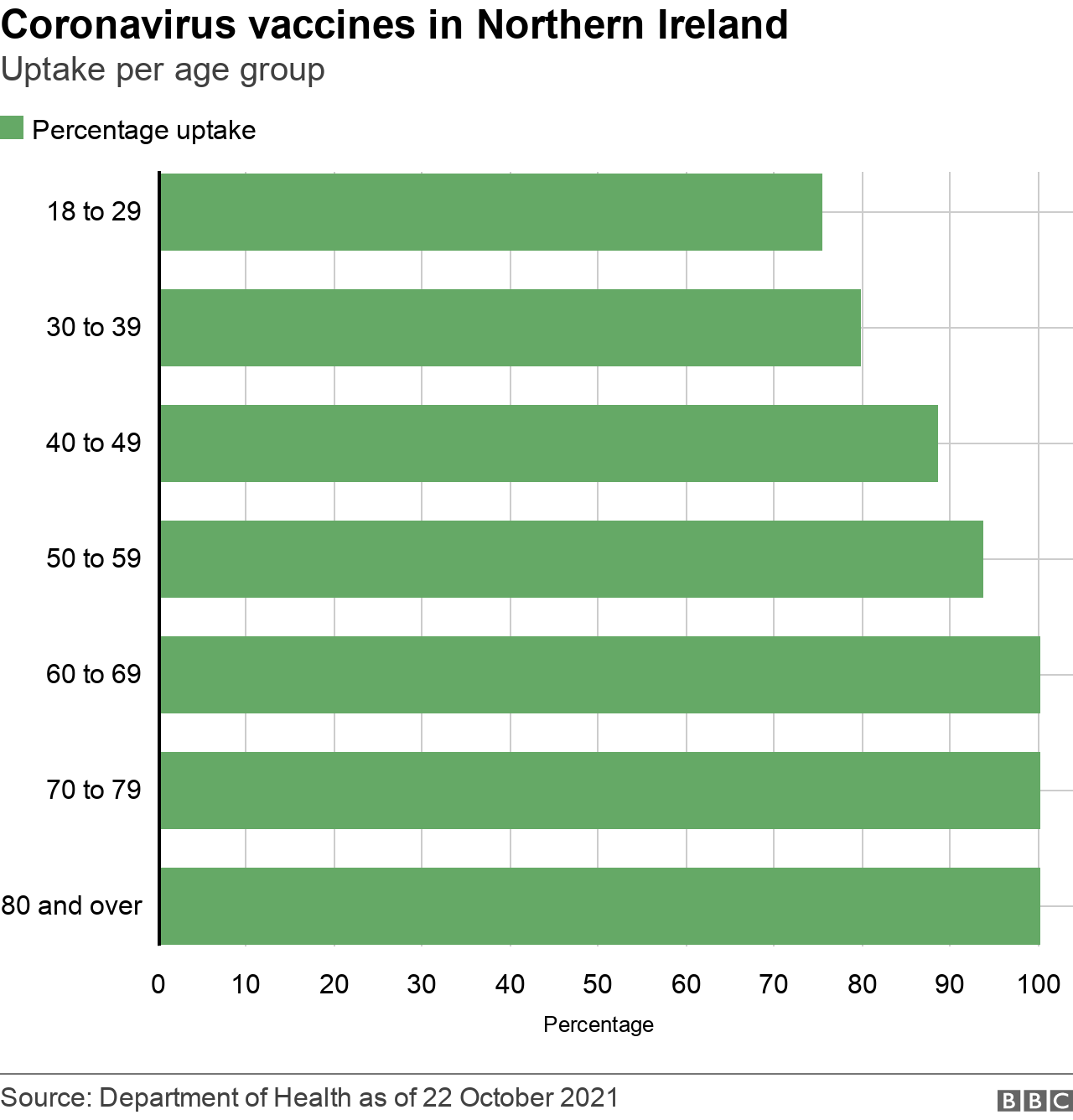

Northern Ireland has the lowest vaccination rate in the UK. We also trail behind the Republic of Ireland.

That has been the case for quite some time.

First dose vaccinations are still happening in Northern Ireland but they have slowed to a couple of hundred a day.

Altogether, 1,319,509 people in Northern Ireland have received at least one dose of vaccine.

The following is the uptake of vaccine by first dose in the UK population aged 12 and over:

England - 85.9%

Scotland - 89.9%

Wales - 88%

Northern Ireland - 82.6%

It remains the case that the lowest uptake of vaccine has been among teenagers and young adults, those aged between 16 and 30.

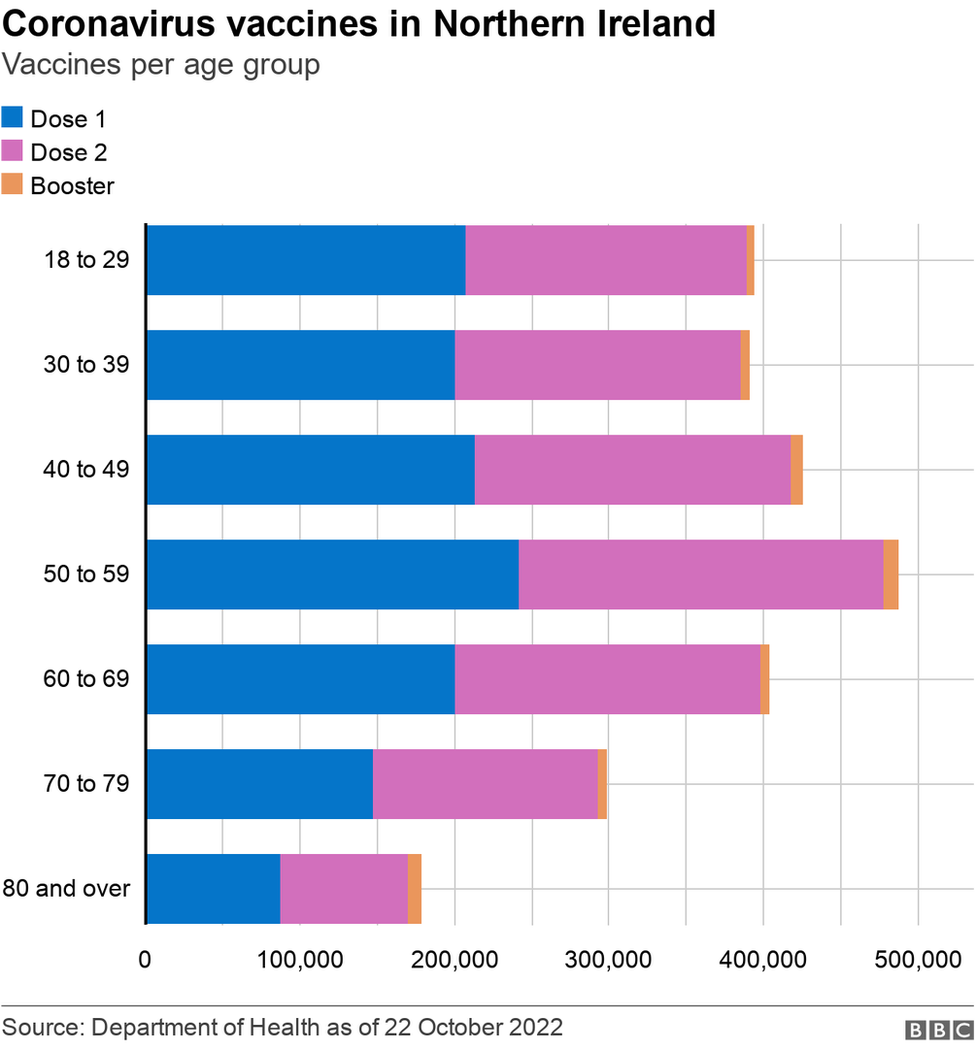

We have now moved into the period of booster jabs and third doses.

Those are being given to people who received their second dose at least six months ago.

It's worth differentiating between these:

Third doses are being given to people who are clinically extremely vulnerable and who might not have higher levels of antibody protection. They may still get a booster dose (effectively a fourth jab) at some stage

Booster jabs are being given to people in high priority groups (the elderly, frontline medical staff)

So far, about 44,000 booster jabs have been given out, along with around 6,000 third doses.

The rollout of these third and booster jabs is slightly different from the beginning of the vaccination programme back in December 2020 and January of this year.

That is because people will have varying degrees of protection against the virus and that protection will wane are different rates for different people.

But the booster programme is key to the attempts to ease the winter burden on the health service.

And health officials will be keen to see people coming forward when called.

Related topics

- Published22 October 2021

- Published21 October 2021