COP26: Where does NI stand on climate change?

- Published

COP26 is a major United Nations conference on climate change, being hosted by the UK and held in Glasgow from Sunday until 12 November.

What does it mean for Northern Ireland?

What is COP26?

It's the 26th Conference of the Parties - the almost-200 states that have signed up to the UN's Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Five years ago the countries met in Paris and agreed to keep global warming to "significantly less" than 2C and as close as possible to 1.5C.

It's significant because now the science indisputably shows that the activity of humans is heating up the world - that has severe consequences for all of us.

Every fraction of a degree of warming matters because it causes extreme weather, affects our ability to grow food, threatens biodiversity and could even make parts of the world that are comfortable now uninhabitable in the future.

Where does Northern Ireland stand?

The answer is: on shaky ground.

Northern Ireland is the last place in these islands to introduce climate change legislation - and even that hasn't been straightforward.

The agricultural sector is a significant part of the economy in Northern Ireland

In March, Green Party leader Clare Bailey brought forward a private member's bill - it set the target of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2045.

That provoked outcry from sectors that see themselves in the crosshairs for having to make cuts to their emissions.

It was followed in July by Agriculture Minister Edwin Poots' bill - that set a target of an 82% reduction in overall emissions by 2050 and was aligned with the Climate Change Committee's views.

The committee doesn't believe Northern Ireland will achieve net zero at the same time as the rest of the UK because of its economic dependence on agriculture.

Committee chair Lord Deben has said Northern Ireland has "a real issue of emissions without the ease of sequestration, which some other parts of the UK have".

Net zero is important because it's the point at which the planet stops heating up.

Put simply, it's when the amount of greenhouse gases - like carbon and methane - that a country is putting into the atmosphere is offset by the steps that country is taking to remove those emissions from the air.

Northern Ireland is the last place in the British Isles to introduce climate change legislation

Those steps might be planting more trees, restoring peat bogs - natural "sinks" that absorb and lock-in carbon - and technological measures, like extracting carbon from the air to store in underground chambers.

Locking carbon away in plants and woodland is also called "sequestration" or "capture".

But because 86% (RSPB NI) of Northern Ireland's peatlands are damaged, and it is one of the least forested places in Europe (8% woodland cover - Woodland Trust), it doesn't have the natural carbon capture resources that the rest of the UK does.

That creates greater pressure for reductions.

What does legislation need to say?

Experts agree that it needs to set realistic targets for the main emitting sectors in Northern Ireland - agriculture, transport, energy (home heating and electricity, for example) - to aim for.

But they diverge on what those targets should be.

Agriculture is the biggest emitter in Northern Ireland, accounting for 27% of greenhouse gases.

Cattle produce methane which makes up much of the emissions in the farming sector

But it's also a huge employer and obviously puts food on supermarket shelves and dining tables.

Some of that food comes from cows, which burp - and otherwise expel - methane into the atmosphere.

There's research into how cows are fed to try to reduce those natural emissions, from adding seaweed to their feed, to putting "powder puffs" on their noses to absorb what they breathe or burp out.

Some say agriculture needs to "green" itself as quickly as possible.

Farmers say that's expensive and will have an impact on their bottom line, not to mention on the consumers' shopping bag.

There's agreement that farmers are crucial to managing climate change, but they want help to do it.

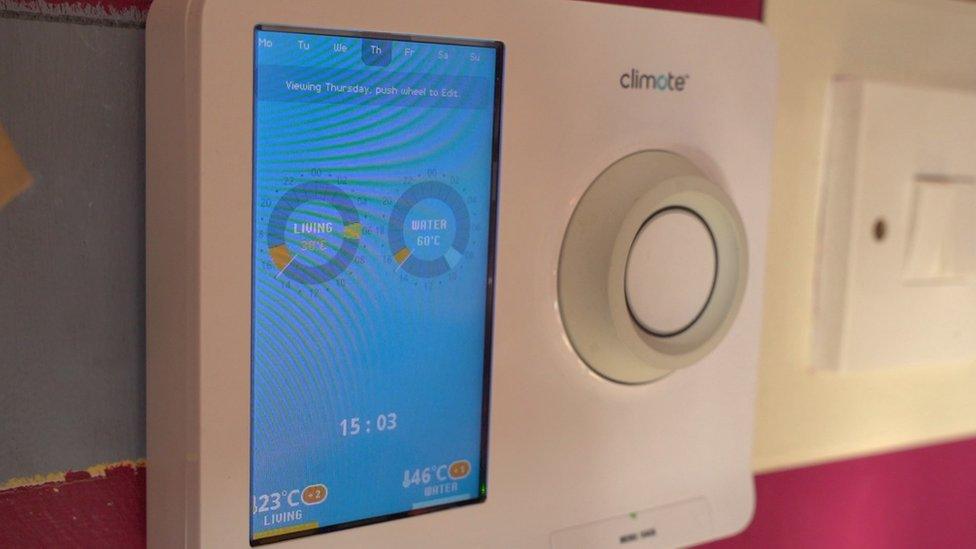

The legislation is also likely to set targets for electrifying transport in Northern Ireland and how people heat their homes.

The electric vehicle charging point network is set to expand and the Housing Executive is trialling a decarbonisation scheme in County Fermanagh.

There are moves afoot to reduce the energy demands in homes and businesses

That means houses being better insulated to reduce their energy demand before something like a hybrid heat pump/oil heating system or solar panels are installed.

But that technology doesn't come cheap and it's not yet clear what support private homeowners will get.

Heat pump systems, which essentially pull in fresh air and "squash" it to turn it into heat for your home, cost from about £6,000.

They can run alongside an oil heating system, which takes over when the temperature gets really low (below 0C, for example).

But the preparation and insulation required can cost another £9,000 or more.

The government announced a grant scheme for householders in England and Wales just ahead of COP26 - nothing has yet been announced in Northern Ireland.

Then there's the drive to generate electricity from green sources such as solar and wind power - an energy strategy is also due to be published soon.

Of course, targets for individuals can't be set but by setting them for different sectors, the Stormont executive and the UK government will hope to drive change in our behaviours and choices, which will also have an impact on our emissions.

- Published15 November 2021