NI 100: The London talks that led to an Irish peace deal

- Published

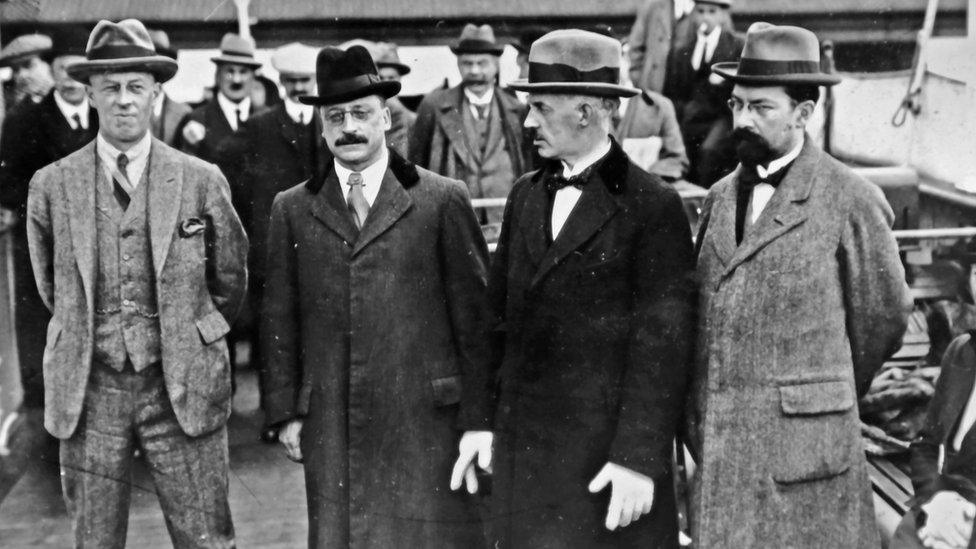

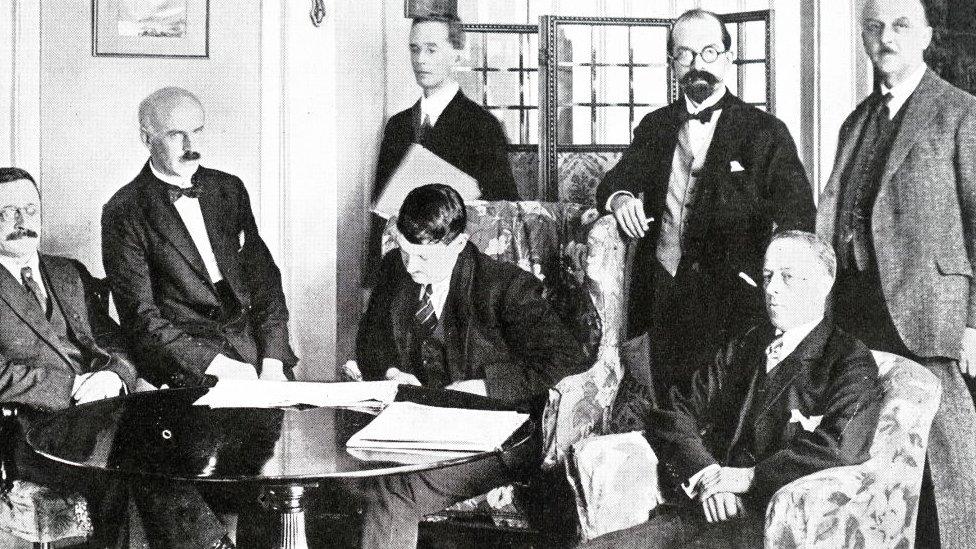

Members of the Irish delegation shortly after the signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921

Few of us make our best decisions in the very early hours of the morning, but one of the most significant political deals in Irish history was signed shortly after 02:00 GMT on 6 December 1921.

A team of exhausted Irish negotiators reluctantly accepted terms that became known as the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The controversial treaty created an Irish Free State, but did not reverse the recent partition of the island.

It also kept Ireland within the British Empire, causing a bitter split among republicans with fatal consequences.

What happened in the fraught, final hours of negotiations and how much pressure did the signatories come under?

The Irish negotiators were told by the British prime minister that a failure to agree to the deal would mean "immediate and terrible war".

The country's fate was in the hands of five men, known as the plenipotentiaries. They were:

Arthur Griffith - founder of Sinn Féin and Irish minister for foreign affairs

Michael Collins - the IRA's director of intelligence and Irish minister of finance

Robert Barton - a former British soldier who became Irish minister of economic affairs

Eamonn Duggan - an Irish lawyer who fought in the 1916 Easter Rising

Gavan Duffy - an English-born barrister whose father was a Young Irelanders leader

Robert Barton, Arthur Griffith, Eamonn Duggan and Gavan Duffy pictured en route to London during the talks

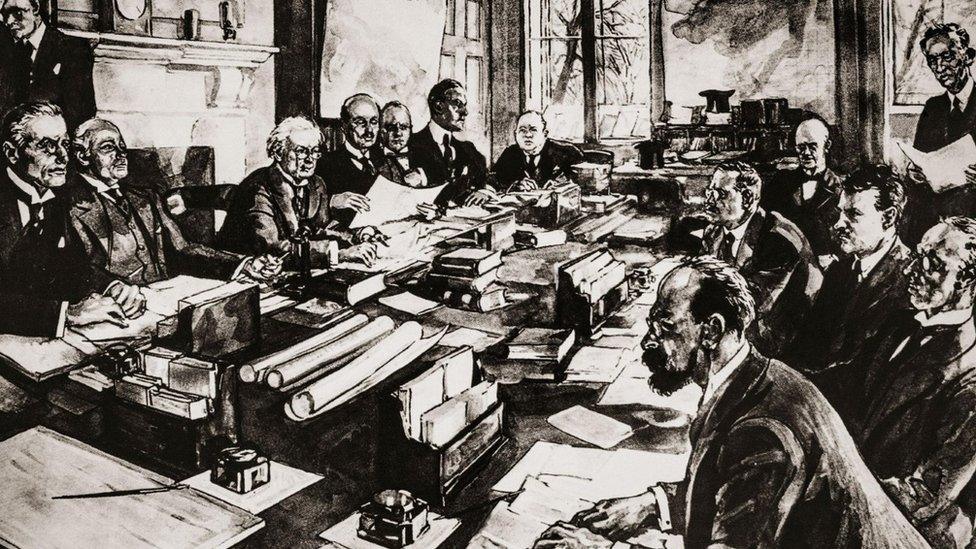

Across the room in Downing Street, they faced a formidable and far more experienced British team.

It included Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who led the UK to victory in World War One, and future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who would lead Britain to victory in World War Two.

They had come to the negotiating table after two-and-a-half years of guerrilla warfare in Ireland, but the Irish team's demand for a united, independent republic was a step too far for the British Empire.

Although both sides were threatening to return to war, the British had considerably more resources. This time, there was also the added threat of participation from unionists in the newly-formed Northern Ireland.

'Looked like he was going to shoot someone'

Only a handful of people witnessed the events of that night, but their recollections give an insight into how the deal was reached.

In his memoirs, Churchill described the Irish delegation as being "in actual desperation and knowing well that death stood at their elbows".

The British team included (left to right) Prime Minister David Lloyd George, the Earl of Birkenhead and Winston Churchill

He recalled Lloyd George delivering the ultimatum on the afternoon of 5 December, with Arthur Griffith promising to return that night with the Irish delegation's response.

At that point, surprisingly, Griffith revealed he had already decided to sign the document himself, even before the other plenipotentiaries had made their decisions.

As the Irish team left to begin their final discussions, Churchill recalled: "Michael Collins rose looking as if he was going to shoot someone, preferably himself."

Read more about the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Griffith's early declaration was evidence of the emerging split in the Irish team, but Lloyd George demanded an unanimous answer, warning there would be no deal unless every plenipotentiary signed.

The prime minister was under intense pressure from his own government, angered by his handling of the talks.

Lloyd George's own political future was at risk and he was about to up the stakes.

Destroyer on standby?

According to Robert Barton's official notes of the night of 5/6 December, external, the Lloyd George warned he had two letters ready to send to Northern Ireland's new Prime Minister Sir James Craig.

One letter would inform Craig a deal had been accepted, the other would announce the Irish delegation had failed to come to an agreement.

"Lloyd George stated that he would have to have our agreement or refusal to the proposals by 10 o'clock that evening. That a special train and destroyer were ready to carry either one letter or the other to Belfast and that he would give us until 10 o'clock to decide," Barton wrote.

(Left to right): Gavan Duffy, Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and Robert Barton during the London negotiations

Historian Prof Colum Kenny, author of Midnight in London, The Anglo-Irish Treaty Crisis, has studied the final hours of the negotiations in detail.

He says had the plenipotentiaries decided to "call Lloyd George's bluff", the British would have been in a strong position to resume hostilities, but this time with even greater force.

"At that stage the British Army was freed up from World War One and its aftermath and the British would have been free to pour in real soldiers - not the kind of ragtag Black and Tans and Auxiliaries that had been operating - and in considerable numbers," Prof Kenny said.

The historian added many leading republicans, including Collins, were aware the IRA was not in a fit state to continue the war even at guerrilla level, and "certainly not to take on all-out hostilities, in which you might have had the Ulster Volunteers armed and participants".

"If it was a bluff, it was a very dangerous one for both sides because had he not delivered on it, Lloyd George probably would have lost his position as prime minister almost immediately," Prof Kenny added.

"Yet had he delivered on it, the consequences in Ireland would have been terrible."

London's Irish community prayed for peace outside Downing Street during the 1921 talks

Barton, an unlikely republican due to his family background, knew the consequences of war better than most.

The former British soldier was born into a Protestant, unionist, landowning family in County Wicklow and had lost two brothers in World War One.

He resigned from the Army in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising and became a staunch republican.

Barton agonised over his decision and was one of the last to be persuaded to sign.

"Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, and Eamonn Duggan were for acceptance and peace; Gavan Duffy and myself were for refusal," Barton told the Dáil (Irish parliament).

"For myself, I preferred war. I told my colleagues so, but for the nation, without consultation, I dared not accept that responsibility."

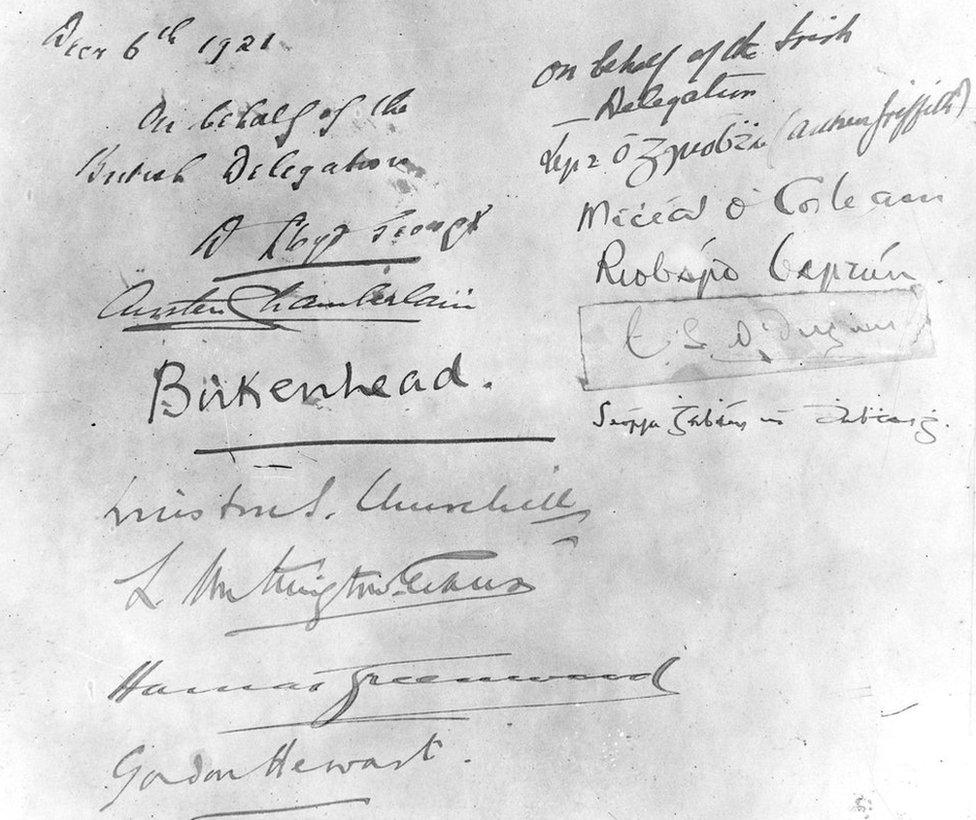

The British and Irish signatures on the document that outlined the terms of the treaty

But Collins told the same Dáil debate he had not been intimidated by the threat of war and stood by his decision to sign the agreement.

Due to his senior position within the IRA, Collins' support for the treaty was important to the British government - Churchill noted his "prestige and influence with the extreme parties in Ireland".

Collins said he understood rejecting the treaty would be a "declaration of war" and he was prepared to fight, but wanted that choice to be put to the Irish people first.

"I signed it because I would not be one of those to commit the Irish people to war without the Irish people committing themselves to war," he told the Dáil.

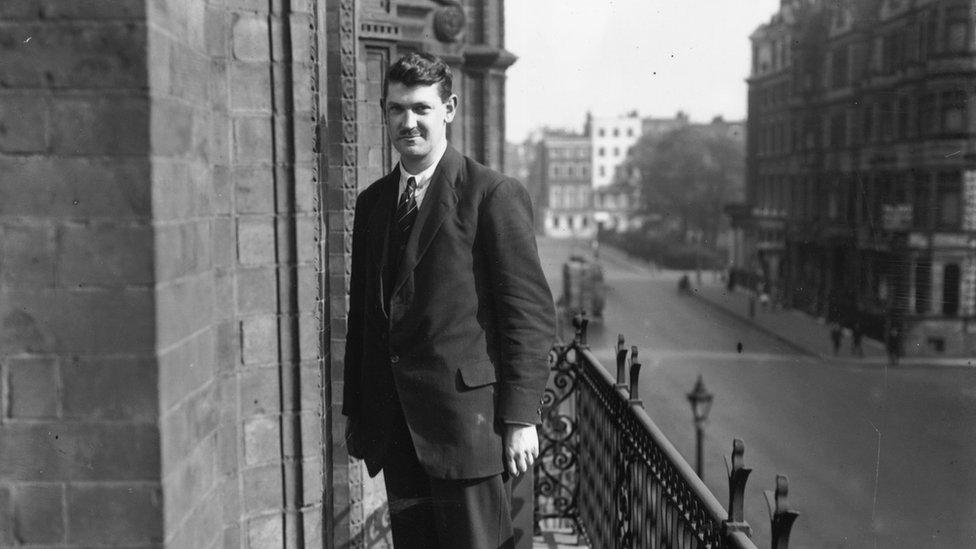

Michael Collins pictured at 22 Hans Place, London, the Irish team's HQ during the talks

Prof Kenny explained the document the plenipotentiaries signed was not the actual treaty, but an "agreement for a treaty" which still required Dáil ratification.

"It would be very hard for any human being in that situation to have chosen to plunge their country into war when there was still the 'out', if you like, when they went back to Dublin, for the Dáil to reject the agreement after discussions," he said.

In the Dáil debates, Collins spoke in support of the agreement, arguing that although not ideal, he was recommending it to the nation because of the "immense powers and liberties it secures".

"In my opinion it gives us freedom - not the ultimate freedom that all nations desire and develop to, but the freedom to achieve it," he said.

Dáil members accepted the treaty by 64 votes to 57 and Collins became head of the new state's government and its army.

But within months, republican divisions over the treaty led to the Irish Civil War.

More than 1,000 people were killed in the conflict, including 31-year-old Collins.

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created 100 years ago by listening to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published11 October 2021

- Published11 July 2021

- Published23 June 2021

- Published6 December 2021

- Published6 December 2021

- Published6 December 2021