NI 100: Why did de Valera refuse to attend 1921 treaty negotiations?

- Published

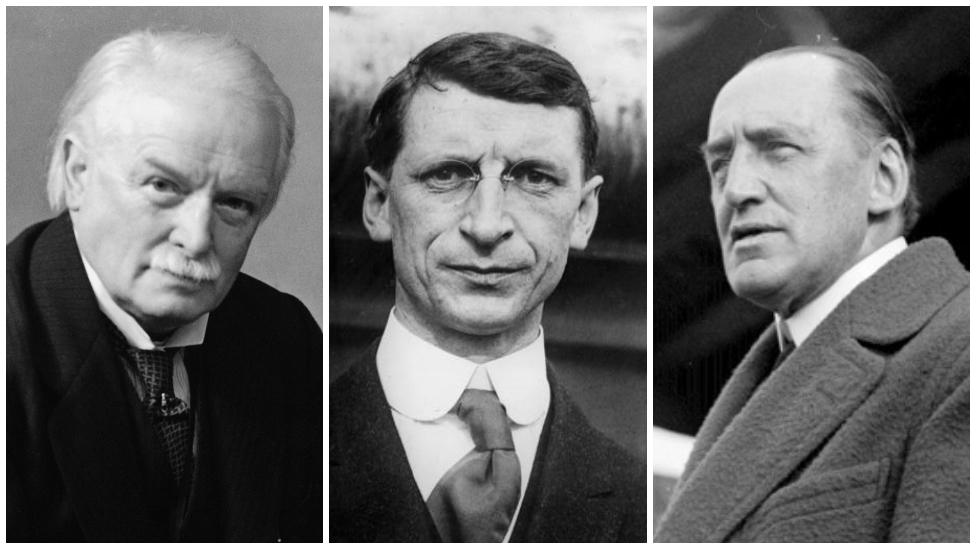

Éamon de Valera, pictured on a tour of his native America during the 1919-1921 Irish War of Independence

On this day 100 years ago, negotiations began in London which led to the turbulent birth of an Irish Free State, a seismic step towards full independence.

But Éamon de Valera, the man with the best claim to lead an independent Ireland, refused to travel to London to negotiate.

He stayed at home in Dublin and sent five other men to negotiate on his behalf.

His failure to attend the talks in person caused bewilderment in 1921 and a century later his motives are still the subject of speculation and intrigue.

Born in the United States to an Irish mother and a Spanish father, de Valera was one of Ireland's most influential statesmen.

A maths teacher by profession, he fought in the 1916 Easter Rising and rose to prominence shortly afterwards as the rebellion's only surviving commandant.

Nicknamed the Long Fellow, his subsequent political career spanned a remarkable six decades, becoming taoiseach (Irish prime minister) three times and serving 14 years as president of Ireland.

But he is also a divisive figure, and much of the controversy that dogs his legacy stems from the decisions he took - and failed to take - at the time of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Barriers were in place in Downing St in October 1921 as crowds prayed for a peaceful outcome to the talks

When the talks opened, de Valera was the leader of Ireland's largest democratically-elected party, Sinn Féin.

Although the British prime minister had met him in London before, and was prepared to do so again, de Valera repeatedly refused to go.

"There were those, at the time, who felt that this was a curious logic because he was their most experienced statesman," says historian Prof Diarmaid Ferriter.

He adds that some of de Valera's cabinet colleagues were "disturbed" by the decision, including the future Irish leader, WT Cosgrave.

"The way WT Cosgrave put it, it's like sending out a sports team but leaving your best player at home."

Scapegoats?

Was de Valera trying to avoid being personally blamed if the talks failed, having predicted the British prime minister would not give in to demands for a united Irish Republic?

Many critics have accused de Valera of making scapegoats of his negotiating team for accepting a deal which fell short of republican hopes, while he refused to share any of their burden or risk.

However, Prof Ferriter argues that rather than a self-preservation ploy, de Valera's decision to stay at home was more of a strategic miscalculation, fuelled by his growing egotism.

"De Valera was used to deference. He was at that stage the sole surviving commandant of 1916, he had a particular stature and standing nationally and internationally," the historian explains.

"He made a strong case at the time for the need for him to remain at home to be the symbol of a unified republican movement."

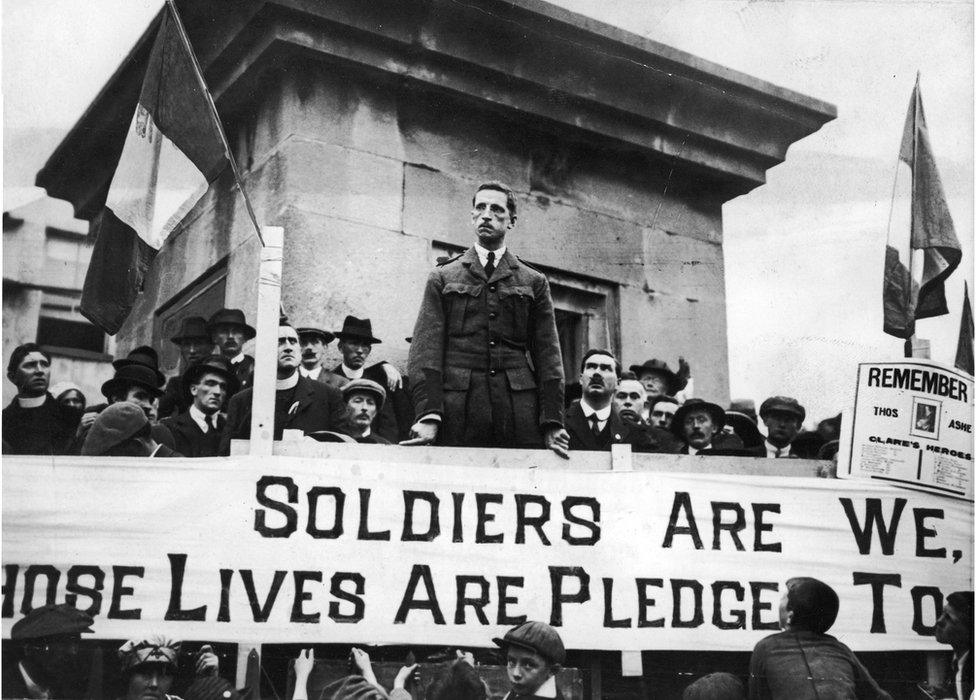

Éamon de Valera speaking in Ennis, County Clare after his election victory as East Clare MP in 1917

De Valera took his position as Ireland's de facto head of state extremely seriously and claimed his distance from London gave him a "tactical advantage".

But by dictating strategy from Dublin, he put the Irish delegation at a disadvantage from the start.

'Ulster question'

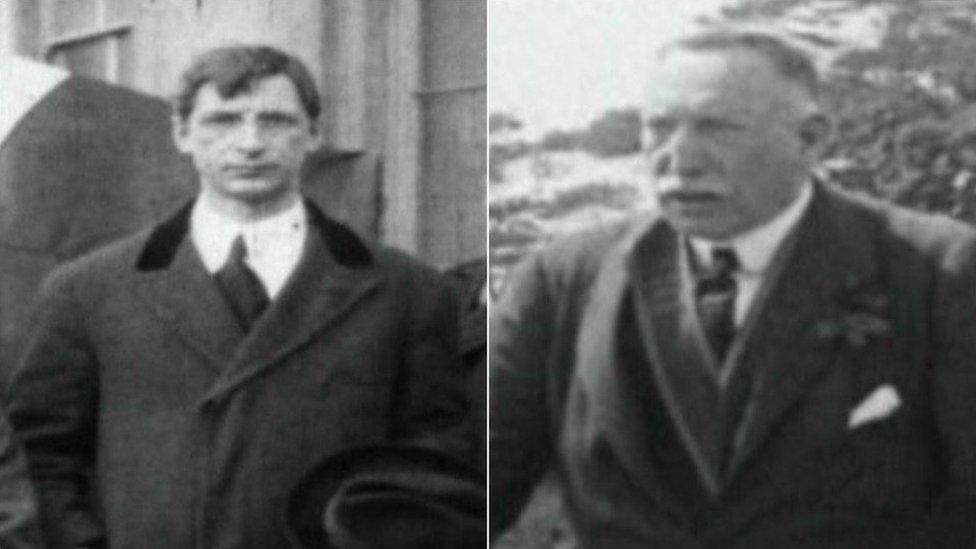

The delegation was led by two high-profile ministers from de Valera's provisional government - Michael Collins, who was also the IRA's director of intelligence, and Arthur Griffith, who founded Sinn Féin.

They were appointed as "plenipotentiaries" and yet were instructed not take any final decisions without their cabinet's permission.

In his biography, Will to Power, Ronan Fanning accused de Valera of failing to explain his strategy properly to the plenipotentiaries before the talks began.

"What passed for the Irish treaty proposals, that the plenipotentiaries brought to London, were fragmentary and slight.

"They made no mention of Ulster, for example," Fanning wrote.

Britain had already partitioned six Ulster counties from the rest of the island in May 1921 and yet the Irish negotiators "didn't have their bottom line on the Ulster question worked out," says Prof Ferriter.

"Arthur Griffith, as leader of the delegation, had to await instructions from de Valera on what their final last or policy should be - that doesn't put you in a very strong position," he added.

After two months of negotiations, in the early hours of 6 December 1921, Collins and Griffith signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, without de Valera's permission.

Michael Collins (centre) and Arthur Griffith (left) shortly after the signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921

What was in the treaty?

The contentious peace deal created an Irish Free State, but did not reverse Irish partition, promising only a review of the path the existing border had taken.

And instead of a sovereign republic, the treaty granted dominion status, which meant staying in the British Empire and swearing allegiance to its king.

De Valera quickly denounced the deal and would have sacked the plenipotentiaries were it not for pressure from his remaining cabinet.

A month later, the treaty was approved by 64 votes to 57 in Dáil Éireann (the Irish parliament).

De Valera resigned as president and was replaced by Griffith.

Éamon de Valera speaking out against the Anglo-Irish Treaty to a huge crowd in Dublin's Cork Street in 1922

Public opinion was sharply divided on the treaty and by the summer of 1922, it led to civil war.

De Valera survived the Irish Civil War and outlived many of his pro-treaty opponents.

But even into his final years, the 1921 controversy "continued to trouble him greatly because he was concerned about the verdict of history", says Prof Ferriter.

Writing in 1963, an elderly de Valera set out several, sometimes contradictory, reasons defending his decision not to attend the London talks.

Perhaps the most obvious reason was that he saw it as a delaying tactic.

He argued that having to refer British proposals back to Dublin "added strength to the position of the negotiators" as it gave them more time to respond when things got difficult.

And if negotiators succeeded in securing the deal he envisaged, he would be needed to sell the agreement to the Irish public, especially hard-line separatists.

Éamon 'the Long Fellow' de Valera with Arthur Griffith in July 1921

So what was the deal that de Valera would have settled for?

In his 1963 letter, he explained his vision of "external association".

It was a third way between dominion status and an independent republic, under which:

Ireland would be linked to the British Commonwealth, but would not become a member

Ireland would control its domestic affairs, but would be associated with Commonwealth states for "purposes of common concern" including defence and war

The king would not be Ireland's head of state, but Ireland would "recognise His Britannic Majesty as head of the association".

It was a complex proposal which he struggled to explain even to his own negotiators.

An exasperated Griffith later complained: "We are outside the British Empire according to this explanation... but we happen to be inside it for peace, war, defence, treaties, and for all vital concerns."

Ego trip?

De Valera's refusal to lead the delegation remains "the most controversial decision" of his career, according to Fanning's biography.

Fanning adds that when the Dáil debated the deal, it became clear de Valera "opposed the treaty not because it was a compromise, but because it was not his compromise".

Taoiseach de Valera taking the salute at Dublin's government buildings after finalising the new Irish constitution in 1937

Prof Ferriter agrees with that assessment, saying vanity and "a lot of ego" played a part in de Valera's mishandling of the talks.

"History has understandably been quite harsh on him," he adds.

"And of course, his opponents could never forgive him because what he ultimately ended up doing, particularly from the 1930s on, was actually proving that this [treaty] could be a basis for further freedom, that the treaty could provide a stepping stone as Collins had famously argued."

The Long Fellow played the long game, and by 1932 he was back in power, rewriting Ireland's constitution and using the plenipotentiaries' hard won concessions as a platform to gradually gain greater independence from Britain.

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

Year '21: You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created a hundred years ago in the company of Tara Mills and Declan Harvey.

Listen to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch-up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published23 June 2021

- Published5 May 2021

- Published21 December 2020