NI 100: Anglo-Irish Treaty vote 'pivotal' in Ireland's history

- Published

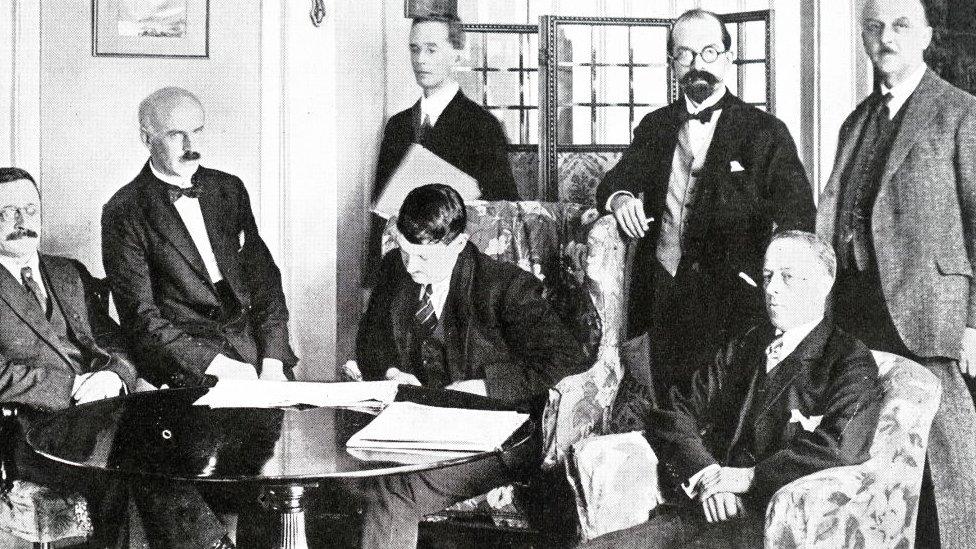

Members of the Irish parliament after one of the Anglo-Irish Treaty debates

The treaty which set up the Irish Free State was ratified in Dublin exactly 100 years ago.

It was a significant step on Ireland's political journey to full independence from Britain.

But opinion on the Anglo-Irish Treaty was split, and within six months an Irish civil war broke out.

Prof Marie Coleman, an historian at Queen's University in Belfast, regards the ratification as a pivotal moment in Irish history.

The deal was passed in the Dublin parliament, Dáil Éireann, by 64 votes to 57 on Saturday 7 January, 1922.

Prof Coleman said: "There were four votes in it. All you needed was four people to change their minds and you would have had a very different outcome."

The narrow margin demonstrated the division in Ireland over the agreement, which was signed at Downing Street on 6 December 1921.

Irish negotiators Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith argued that the new self-governing Irish Free State offered a pathway to full independence and the re-unification of Ireland, after the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921.

Opponents of the treaty, led by Éamon de Valera, felt it did not go far enough.

They wanted a 32-county independent republic and believed the agreement, which included an oath to the King, was inadequate.

Could a vote before Christmas have made a difference?

The December deal was followed by debates in the Dáil, external but the vote was not until the new year.

"There is a school of thought that had the vote been taken before Christmas, the outcome could have been different," said Prof Coleman.

Prof Marie Coleman said it would have taken just four people to change their mind for "a very different outcome"

"The debates started in December, took a break for Christmas and then resumed in January.

"When a lot of the TDs (Teachtaí Dála or members of the Irish parliament) went home to their constituencies, they came under a lot of pressure from vested interests, particularly the Catholic Church, to support the treaty because they didn't want to see a return to violence."

Split opinion

The treaty was signed six months after the Anglo-Irish War ended, with a truce in July 1921.

If a deal had not been signed by the end of the year, the conflict was expected to resume.

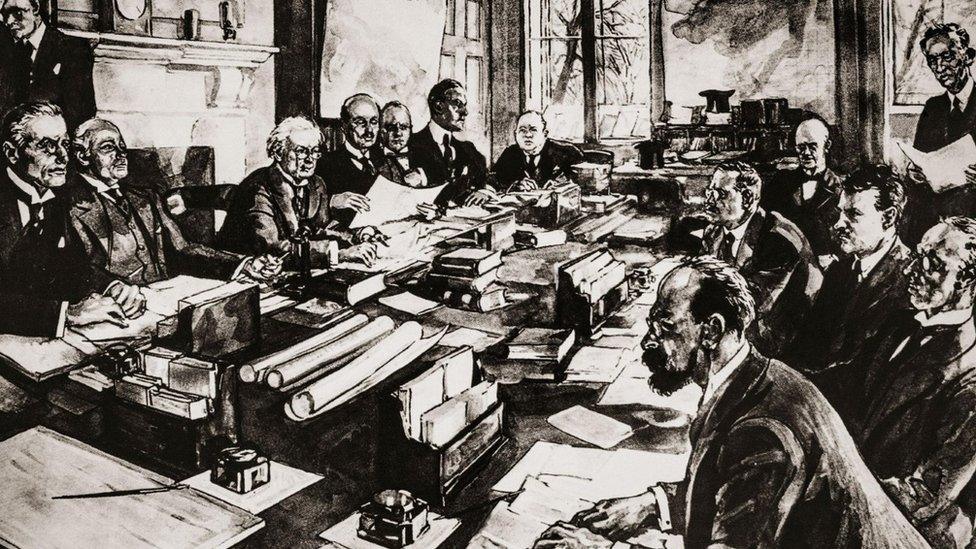

Members of the Irish delegation shortly after the signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921

The split in opinion among politicians was mirrored in other aspects of life, with some families divided on the issue.

Before and after the treaty was ratified, Ireland was gripped by arguments over it.

Prof Coleman said: "The Catholic Church was very much in favour of the treaty and of anything that would bring an end to violence.

"The GAA (Gaelic Athletic Association) kept out of the political side of it but afterwards [after the civil war] it was an important force in trying to heal some of those divisions."

Short-lived peace

The civil war broke out in the summer of 1922.

Before the end of that year, the two key supporters of the treaty - Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith - were dead.

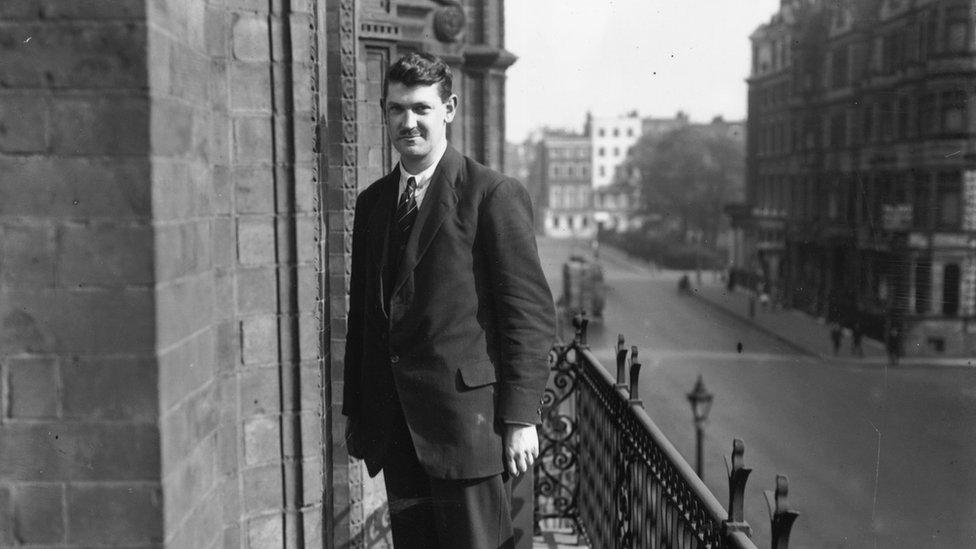

Michael Collins pictured at 22 Hans Place, London, the Irish team's HQ during the talks

Griffith died after a heart attack in August at the age of 51.

The same month, Collins was shot dead at Beal na Bláth in County Cork. He was 31.

Their deaths did not stop the enactment of the treaty.

The Irish Free State was set up as planned in December 1922.

Northern Ireland was given the option of joining the newly-created state but the unionist government in Belfast made it clear it had no intention of doing so.

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the 100th anniversary of the creation of Northern Ireland and partition of the island.

There are special reports on the major figures of the time and the events that shaped modern Ireland available at bbc.co.uk/ni100.

You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created 100 years ago by listening to the latest Year '21 podcast on BBC Sounds or catch up on previous episodes.

Related topics

- Published6 December 2021

- Published6 December 2021

- Published6 December 2021