NI election results 2022: Sinn Féin's rise from IRA political wing

- Published

Sinn Féin, pictured at the party's manifesto launch, described its election performance as "historic"

In the late 1980s, when I first arrived in Belfast as a young reporter, Sinn Féin were routinely described on the BBC airwaves as "the political wing of the IRA".

Sinn Féin wasn't coy about its relationship with the IRA.

If you asked Gerry Adams or Martin McGuinness to denounce an IRA bombing or shooting, they were likely to tell you they didn't engage in "the politics of condemnation".

The Sinn Féin newspaper An Phoblacht (Republican News) featured a column entitled War News which proudly detailed the latest IRA ambushes on what it described as British "crown forces".

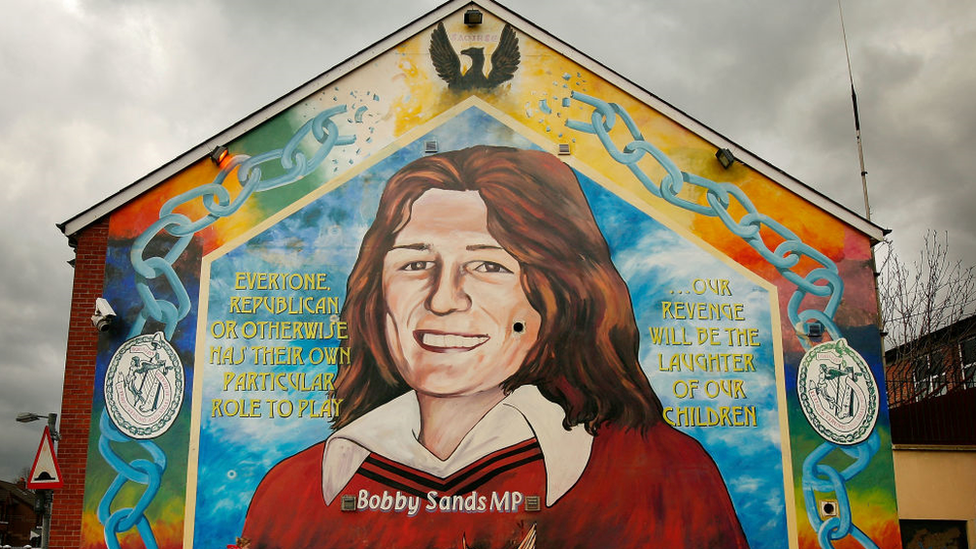

The party office on the Falls Road in west Belfast was emblazoned with an iconic mural of Bobby Sands.

Bobby Sands was the IRA prisoner who secured election as an MP in 1981, before dying on hunger strike inside the Maze Long Kesh prison.

If you had told me back then that, 41 years to the day that Bobby Sands died, the voters would be elevating Sinn Féin to the top spot as Northern Ireland's biggest party, I would have been sceptical, to say the least.

Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness pictured at an IRA funeral in 1987

A former Northern Ireland Secretary, Douglas Hurd, once derided Gerry Adams as "Mr 10%" - a sobriquet designed to emphasise that Adams only spoke for a minority of nationalists.

Now Michelle O'Neill is "Ms 29%" - in possession of a quarter of a million first preference votes.

A clear lead over the DUP in Stormont seats, and, potentially, the keys to the Stormont first minister's office.

How did this transformation happen?

In the 1980s, Bobby Sands pioneered the foray into electoral politics, but in the Irish Republican "ballot box and Armalite rifle" dual strategy, the Armalite remained on top.

But in the 1990s, Gerry Adams persuaded the reluctant militarists in Republican ranks that turning the IRA's violence off could achieve more in their quest for Irish unity.

The eventual success of Adams' strategy was undoubtedly hastened by the willingness of the more moderate nationalist SDLP leader John Hume to "sacrifice his party for his country".

Hume shared his immense influence and access in the USA and Dublin with Adams, in the interest of securing peace. The paramilitary ceasefires and the Good Friday Agreement followed.

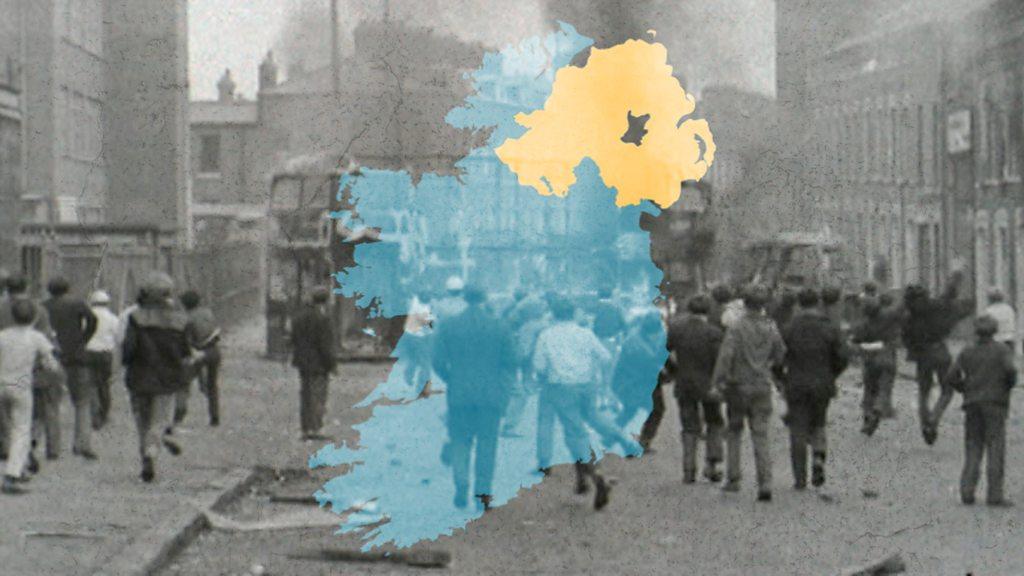

The Good Friday Agreement was signed on 10 April 1998 and helped bring an end a period of conflict in Northern Ireland called the Troubles

Buoyed up by huge domestic and international attention, Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness transformed their movement into a political force which, in the 2000s, overtook the SDLP as the biggest nationalist party, before 20 years later supplanting the DUP as the biggest party overall.

It is no mean achievement and to pull it off Sinn Féin has drawn on the kind of discipline and organisation which it developed during the Troubles, a keen grasp of the issues on the mind of the growing nationalist community (many too young to have first-hand memories of the bad old days) and a war chest full of cash.

The party is generally left of centre and populist in its approach and has proved able to discern changing attitudes, shifting its ground on issues as diverse as women's rights, the EU or diplomatic relations with Russia.

Although the party doesn't hide its commitment to a united Ireland, it won its latest mandate on the back of a deliberately low-key campaign with a soft focus, featuring Michelle O'Neill working out in the gym and promising she would be "a first minister for all".

Putting one over on the DUP and unionism might have been a large part of the appeal for nationalist voters, but Sinn Féin didn't have to say it out loud.

The continuing presence of veteran IRA figures within the party's Stormont ranks emphasises that, while much has changed, the party's primary motivation remains the same.

What would have surprised my 1980s self even more than Sinn Féin's current dominance at Stormont is the situation in Dublin, where the party, led by Mary Lou McDonald, is now consistently topping the polls.

A mural of Bobby Sands on the Falls Road in Belfast

It's not inconceivable to imagine a Sinn Féin Stormont first minister meeting a Sinn Féin taoiseach (Irish prime minister) sometime in 2025, when the next Irish election is due.

Sinn Fein's goal of uniting Ireland north and south remains some way off.

The current balance at Stormont is roughly 40% nationalist 40% unionist with 20% preferring to steer clear of traditional green orange politics.

Moreover, the latest opinion polls still point to majority support for staying in the UK.

But Sinn Féin's ascendancy is an important, symbolic, moment and a remarkable example of a movement exchanging the gun for the ballot box and then exceeding all expectations.

Bobby Sands famously said that Irish republicans' revenge on their enemies would eventually be the "laughter of our children" and 41 years on republicans definitely have something to smile about.

- Published8 May 2022

- Published13 August 2019

- Published12 May 2022

- Published10 April 2018