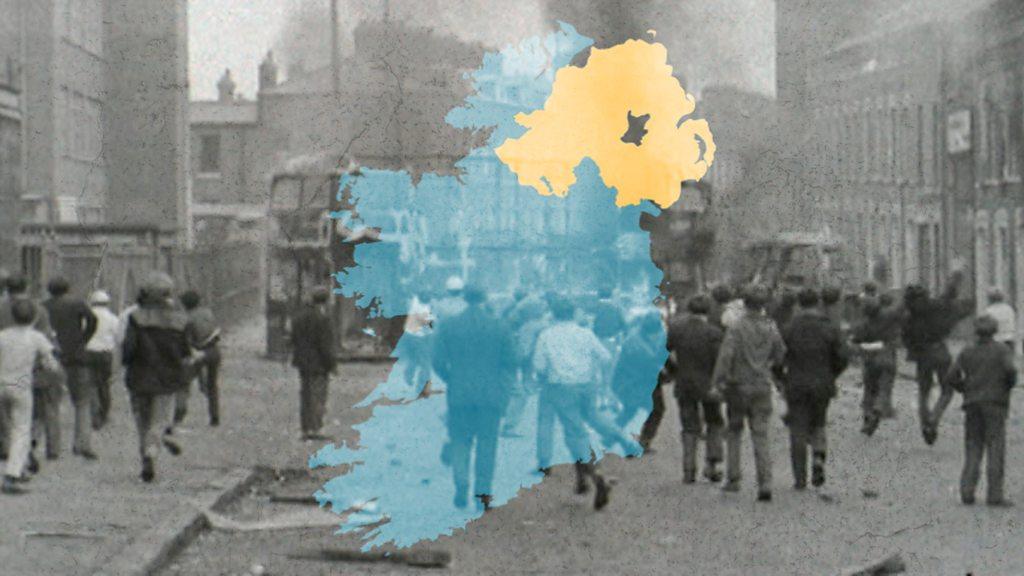

NI Troubles: Legacy bill published by the UK government

- Published

The government has introduced legislation that aims to draw a line under the Northern Ireland Troubles by dealing with so-called legacy issues.

The Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill runs to almost 100 pages.

It is an attempt to deal with more than 1,000 unsolved killings.

A central element involves immunity from prosecution for those who co-operate with investigations run by a new information recovery body.

Bereaved families can request investigations, as can the government and others.

The Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery (ICRIR) will be headed by a judicial figure appointed by the government.

It would be operational for five years.

A panel within the ICRIR will be responsible for deciding if a perpetrator qualifies for immunity.

The draft legislation states it must be granted if an individual gives an account judged to be "true to the best of (their) knowledge and belief".

Once granted, it cannot be revoked.

In last week's Queen's Speech, the government announced it was changing its original proposal from last July, which would have ended all Troubles-era prosecutions - effectively an across the board amnesty.

Analysis: 'No more talking'

After a legacy bill failed to materialise in the last parliamentary term, the government has moved at pace.

It is only a week since the Queen's Speech and, by the look of it, there is to be no more talking.

Axing the idea of a blanket amnesty has done little to gain support from either victims' groups or political parties.

The overall package, they argue, remains exclusively UK designed with no buy-in in Northern Ireland.

One opponent told me things have now entered "wreck the bill territory".

It remains to be seen what amendments may emerge in Parliament, but the government has the numbers.

The legislation will almost certainly face legal challenge around whether investigations meet standards of effectiveness.

The government has said the plan "complies fully" with international human rights obligations, but some victims' families are already geared up to challenge it.

The legislation will prevent future inquests and civil actions related to the Troubles.

Civil claims which already existed on or before the day of the bill's introduction will be allowed to continue, as will inquests which have reached substantive hearing stage a year after the bill, or by the time the ICRIR becomes operational.

NI Secretary Brandon Lewis said victims and military veterans were being let down by the current system

Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis said the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill would help society look forward.

"This is a very difficult area and it can be very painful for people," Mr Lewis told BBC Radio Ulster's Good Morning Ulster programme.

"One of the challenges is the current system isn't working for people. That's very clear."

He said the legislation would "give people a reason to come forward and a motivation to come forward that at the moment simply doesn't exist".

Asked if people under investigation or facing charges could then give information in exchange for immunity, Mr Lewis said: "The independent body would take the view on if people have engaged in the right way and shared their information."

Kenny Donaldson said the justice offered by the bill was only "tokenistic"

The Northern Ireland secretary also announced the government's intention to commission an official history relating to the Troubles, conducted by independent historians.

Underpinned by "unprecedented access to the UK documentary record", he said this would provide an in-depth examination of the "government's policy towards Northern Ireland during the conflict".

The government has previously indicated that the legacy legislation would not be rushed through Parliament under accelerated passage.

It could take many months to become law.

How have victims' groups and veterans' groups reacted?

Kenny Donaldson, spokesman for Innocent Victims United, said members of his 12,500-strong group were "unhappy that justice, in many ways, is being taken off the table".

"It's being left on in a tokenistic and symbolic fashion, but not with any real teeth," he said.

Campaigner Mark Kelly, whose 12-year-old sister Carol Ann was killed by a plastic bullet fired by a soldier in Belfast in 1981, said the government's proposals still amounted to an amnesty.

"They can paint it and colour it whatever way they like, but what they're trying to do is tell British soldiers that: 'No matter what you did in the north of Ireland, not only will there be no investigations into it," he said.

Michelle O'Neill accused the government of trying to "pull down the shutters on family campaigns for truth and justice"

Alan McBride, from victims' group the Wave Trauma Centre, said while the new proposals were better than the previous blanket amnesty, he was "not so sure it is a huge improvement".

"You could also probably argue that was a negotiation tactic from the British government in that they put out something so ridiculous and abhorrent that whatever they were seen to do would always be an improvement to that," he added.

Victims' campaigner Raymond McCord, whose 22-year-old son Raymond Jr, was murdered by the loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), in 1997, described the proposals as "disgraceful and disgusting".

However, Veterans Commissioner Danny Kinahan has given the bill a cautious welcome after months consulting with several veterans' support groups.

"What they really want is the chance to be able to still pursue justice; still follow the rule of law," he said.

"And the changes we've got - which is why I say cautiously welcome - seem to be doing that, in that we're going to have a really, robust panel system which will dig down in for families so they can find out who blew them up, who shot them, who caused the harm."

How have political parties reacted?

Sinn Féin vice-president Michelle O'Neill accused the government of trying to "pull down the shutters on hundreds of family campaigns for truth and justice".

In a tweet, external, she said: "Prioritising the demands of their state forces over families is unjust and cruel. I stand with the families."

Gavin Robinson, of the Democratic Unionist Party, said his party would be studying the detail of this bill but added they would "continue to be a voice for innocent victims".

"If this bill undermines access to justice for innocent victims then it will be a further corruption of justice," he said.

The Alliance party's deputy leader, Stephen Farry, told his Twitter followers the new legislation "lacks legitimacy and credibility".

"This revised Bill has not been designed in conjunction with NI political parties or more crucially with victims' groups," he tweeted, external.

Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) leader Doug Beattie tweeted, external "there can be no amnesty, no immunity from prosecution for acts resulting in death or injury regardless if it happened in UK or beyond".

Social Democratic and Labour Party leader Colum Eastwood said it was a "dereliction of duty" for the government to push ahead with the legislation.

"The people who will lose the most from this new process are those who have already paid the worst price for the failure to deal with the legacy of our past," he added.

Related topics

- Published14 May 2022

- Published11 May 2021

- Published2 January 2022

- Published13 August 2019