Belfast: The hidden castles under the city's shops

- Published

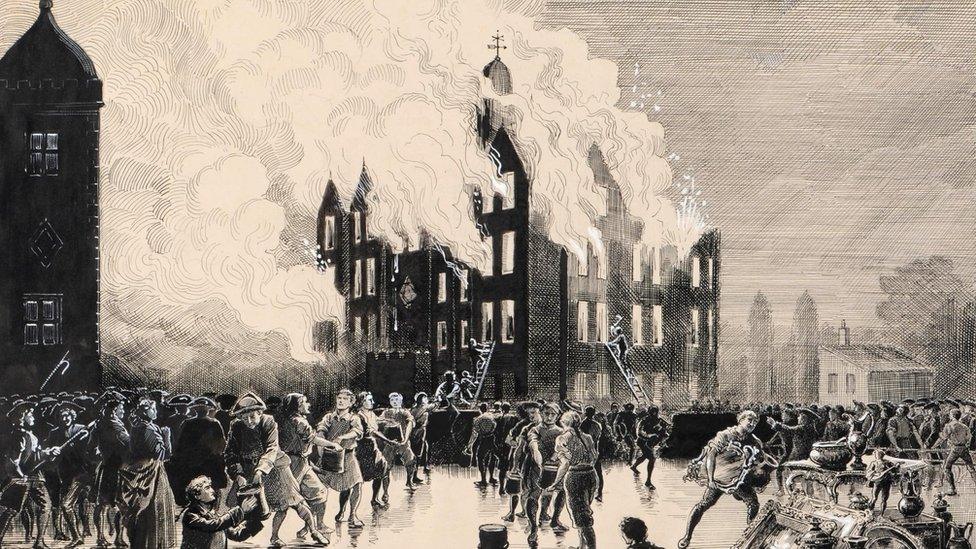

A castle built under the command of Sir Arthur Chichester in the early 1600s was destroyed by fire a century later

The history of Belfast can be told through many of its street names and buildings, much of it reflecting the city's industrial heritage and Victorian boom.

But in one block, under the feet of shoppers, there is a story which dates back several hundred years.

Castle Lane, Castle Arcade, Castle Place and Castle Buildings.

Each pays tribute to the site of not one, but three Belfast castles, and archaeologists believe their foundations and artefacts could still lie below the surface.

Part of the area is the former British Homes Stores (BHS) site, which is now to be converted into a complex of leisure and retail units.

It will be called The Keep, a nod by developers to a past which was first referenced in 1262.

'Strategic base'

Then it was an Anglo-Norman castle, believed to consist of an earthen mound, similar to mottes that remain visible in townlands such as Dundonald.

It was a "critical part of the medieval Norman settlement of Belfast", striding the Farset River, which we now know as High Street, archaeologist Ruairí Ó Baoill told BBC News NI.

However, the site was destroyed in the 1300s, as power shifted to the Gaelic lords in Ireland, such as the Clandeboye O'Neills.

The O'Neills in turn built a new castle, a "strategic base", Mr Ó Baoill explained.

"We know there was a castle there because there are references to it being attacked in the 1400s and the 1500s in both Irish and English histories and it's actually shown in two maps," he said.

Medieval burials have also been documented in Cornmarket, an area which is now home to shops, cafes and buskers.

'The Keep' development site has referenced the castle in its promotional material

According to Queen's University academic Dr Colm Donnelly, the O'Neill castle would have looked like a tower house, "a small building, maybe four storeys high", with rooms stacked on top of one another, connected by a spiral staircase.

Similar stone towers from this period have survived, such as Audley's Castle and Kilclief Castle, close to Strangford.

"They were abandoned by and large in the 17th century, but they survive in the Irish landscape," Dr Donnelly said.

The Clandeboye O'Neill building is believed to have resembled tower houses such as the 15th century Kilclief Castle, near Strangford

"They're really well constructed, but they're not immune from the forces of nature, such as frost getting into the walls."

This second Belfast castle was also replaced, but not entirely.

"At the end of the 16th century the Gaelic lords went into revolt and they were defeated by the forces of Queen Elizabeth I, one of whom was Arthur Chichester," Mr Ó Baoill said.

"He was given land all over the place, including the town of Belfast."

The Chichester castle features prominently to the top right of Thomas Phillips' map of Belfast in 1685

A report by the plantation commissioners in 1611 gives an account of shops being built in the new Chichester town, with 120,000 bricks being used by masons.

Among the writings is a reference to the old "decayed" castle, the O'Neill building, part of which was retained and linked to the new Chichester castle via a staircase.

The third castle survived for a century, but burnt down in 1708, killing four people, including three sisters of the 4th Earl of Donegall.

It can be seen in a map of Belfast in 1685, however, along with the city's walls, which were ground-made ramparts that partly enclosed the town.

"It was smack in the centre of Belfast, around Cornmarket and Castle Arcade," Mr Ó Baoill said.

"Underground are the remains of at least two castles side by side, and possibly the Anglo-Norman one as well, but it's really frustrating because you can't see them."

"Underground they're safe," he added.

Due to the risk of flooding in Belfast, Mr Ó Baoill said archaeologists believed few of the city centre's buildings have deep basements, meaning there is a possibility that "substantial archaeological remains" exist across the area.

The castles, off modern Castle Place, were built at a site of strategic importance, according to Ruairí Ó Baoill

Historian Dr Jim O'Neill agreed and explained a shallow trench he once excavated in Waring Street revealed centuries of buildings had been layered on top of each other, indicating that the castles' remains could exist mere metres underground.

He said it is believed the medieval tower house contained masonry vaulting.

"If you had a limitless budget and luck on your side, you should find this large brick structure with a masonry core, which would be astounding," he detailed.

"It would be astonishing to find that and then, of course, associated with that the remains of domestic life from that time."

'Heightened archaeological potential'

The planned redevelopment of the BHS site has been limited to "areas of previous ground disturbance", the Department for Communities told BBC News NI, with the need for an archaeological assessment "likely to be minimal or avoided entirely".

It added, however, the area was recognised as having a "heightened archaeological potential within the historic core of Belfast".

Ruairí Ó Baoill (red jacket) has previously carried out excavations in Castle Lane in 1983

The department's Historic Environment Division (HED), which advises on the potential archaeological impact on planning decisions, highlighted the history of the location to Belfast City Council, which approved the project.

The council said the planning conditions "ensure appropriate mitigation of any archaeological impacts of development".

Dr O'Neill said the castles had always been of great interest to archaeologists and that local experts would like to excavate in the wider area.

"There's always that possibility, that frisson of excitement that we might get gold in terms of the archaeology of Belfast," he said.

Ruairí Ó Baoill added there remained a "massive interest" from Belfast people too in the city's history as more resources are made available to tell its story online.

"It's frustrating you can't see it [the castle], but just because you can't see it, it doesn't mean it isn't there," he said.

"There are hundreds of years of history back to the Anglo-Normans in the city centre, there's thousands of years in the hills around Belfast.

"We have a really really interesting past, a much longer past than sometimes people believe."

Related topics

- Published11 September 2019