When Ireland was battered on the Night of the Big Wind

- Published

The events of the Night of the Big Wind were recreated for Lagan Media's Oíche na Gaoithe Móire in 2015

It left towns and villages in Ireland looking like battlefields and killed dozens of people, and destroyed tens of thousands of homes.

In comparison with the more recent Beast from the East, the Night of the Big Wind sounds like something that would cause minor inconvenience, judging by its name.

In reality, the 1839 storm is considered the deadliest ever recorded on the island of Ireland.

It struck without warning during the night of Sunday 6 January, bringing hurricane-force winds to a poor and vulnerable country, lasting 12 violent hours.

There had been heavy snowfall the day before but it started to melt on the Sunday due to a burst of warm weather.

Later that night, at about 21:00, the winds, which may also have featured tornadoes, came from the Atlantic and hit the west coast first.

An Enniskillen Chronicle report from the time said that the sound of the wind in County Sligo was like "the deafening roar of a thousand pieces of artillery".

In Donegal, the Ballyshannon Herald reported that "the sea rose to such a height that the poor inhabitants thought it was the end of the world".

The northern half of the island was worst hit - north Connacht, Ulster and north Leinster.

In north Dublin alone, 20 to 25% of homes were reported to have been either destroyed or badly damaged.

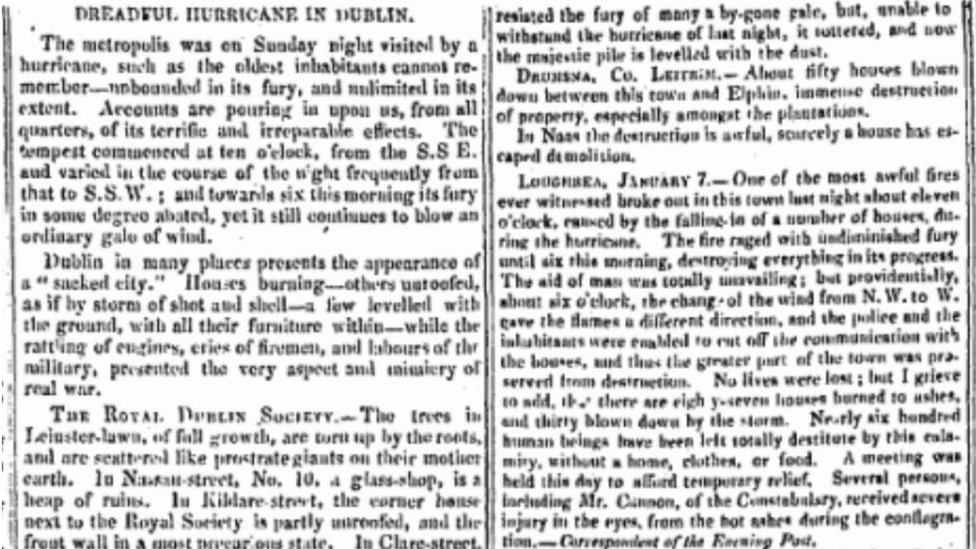

A report of the storm appeared in a copy of the Belfast News Letter in January 1839

"Judging by the damage descriptions the winds' strength were up to hurricane force - up to one or two hurricane category on the wind scale," said Paul Moore of Irish weather service Met Éireann.

"Category two is sustained winds of 96mph to 110mph.

"There's one description that Dublin resembled a sacked city, from one of the news articles of the time, so that's consistent with that strength of wind."

The winds struck an island ill-prepared to withstand them.

"One third of the population was living below the poverty line - you're talking potentially up to about three million people," Dublin City University historian Prof James Kelly explained.

"So there were a lot of people living in what we would identify today as very substandard, perhaps even spartan, conditions which would have meant that they were very vulnerable."

Queen's University Belfast historian Dr Ciaran McCabe added: "A lot of people in rural Ireland, particularly in the west and parts of Leinster and Munster, were living in thatched mud cabins.

"They would either have been levelled or the thatched roof would be be blown off completely.

Dr Ciaran McCabe said Ireland was left looking like a battlefield

"Or in a lot of cases you get reports of fire in houses and buildings being burned down.

"People might have had the fire on and the wind came in the window or door, threw the cinders up into the thatch and that would have caught fire."

But it was not just the shacks of the poor that were destroyed.

Residential, commercial and industrial buildings in urban areas were also damaged.

"Newspaper reports for Belfast, where you have a lot of factories and distilleries, say there was a huge amount of commercial and industrial chimneys being blown down and collapsing," Dr McCabe said.

"The building would be destroyed and there is the occasional instance of them falling on people who were, needless to say, killed.

"A lot of reports in the following days and weeks say that Ireland was left - the town or the village or whatever - almost like a battlefield: damage strewn as far as the eye could see."

It was not just on land that the storm wrought destruction - many people were caught out in boats at the mercy of the winds.

The poverty in Ireland at the time made it particularly vulnerable (reconstruction from Lagan Media's Oíche na Gaoithe Móire)

The captain and 14-man crew of the vessel Andrew Nugent all perished off the coast of County Donegal.

Dozens of other lives were lost at sea.

Inevitably this trail of destruction left many dead and injured.

Met Éireann, using contemporary reports, cited the "surprisingly low" figure of 90 to just over 100 lives lost.

"There wouldn't have been anything like that [in storms] since," Mr Moore said.

However, Dr McCabe said there were other estimates that put the death toll at 300 to 500.

As fallen masonry caused many injuries and deaths, perhaps such figures reflect people who died in the weeks and months afterwards.

As well as the loss of life and the damage to the country's infrastructure, the natural landscape was also ravaged, with hundreds of thousands of trees uprooted.

In one estate alone - Castle Coole in County Fermanagh - the Enniskillen Herald reported that a previous estimate of 15,000 trees destroyed "should be changed to 100,000".

Storm Ophelia in 2017 came close to matching the wind strength of the Night of the Big Wind

It was not the first climatic disaster to hit Ireland that century.

Crops failed in 1816 due to the effects on the northern hemisphere of the Mount Tambora volcanic eruption, in what is now Indonesia.

The year was alternatively known as the "year with no summer" and the "year of the beggar".

There had been local famines in 1822 and heavy rains and flooding in the autumn of 1839 ruined crops and compounded the disaster of the Big Wind.

Then in 1845 came the Great Famine.

"The point that you can make about this whole period is that - and this is what distinguishes it from the present that we don't always acknowledge - there was a vulnerability to extreme weather," Prof Kelly described.

"Exceptional weather was going to take a particularly heavy toll on a population that was already disproportionately poor."

Mr Moore of Met Éireann said while recent storms such as Ophelia in 2017 came close to the strength of the Night of the Big Wind, none have matched it.

He added that Ireland would be much more capable of coping now.

"Now when a storm comes in it's forecast, a lot of the boats come in from sea, but that came without warning," he said.

"The construction of buildings nowadays would be a lot stronger than they were back then, especially for the poor."

Although it would be overshadowed by the disaster of the Great Famine, which started just six years later, Dr McCabe said the Night of the Big Wind was Ireland's "worst storm, certainly in modern history and going back to the 1500s and 1600s".

Prof Kelly said such events "are a constant reminder to us of our frailty in the face of the power of the environment and basically how changeable weather is, how destructive it can be at any particular moment".