Haemochromatosis: Calls for more testing for 'Celtic Curse' in NI

- Published

It is thought that one in 10 people have the condition in Northern Ireland

People whose relatives have a blood condition are often not being screened in Northern Ireland for reasons of cost, a charity has said.

Haemochromatosis - also known as the Celtic Curse - is the most common genetic disorder in Northern Ireland.

Guidance states all close relatives - siblings, parents and children - should be screened if a person is diagnosed.

The Department of Health said screening of people for haemochromatosis would be done if it was required.

The disorder means a person absorbs too much iron and it can start to damage other parts of their body.

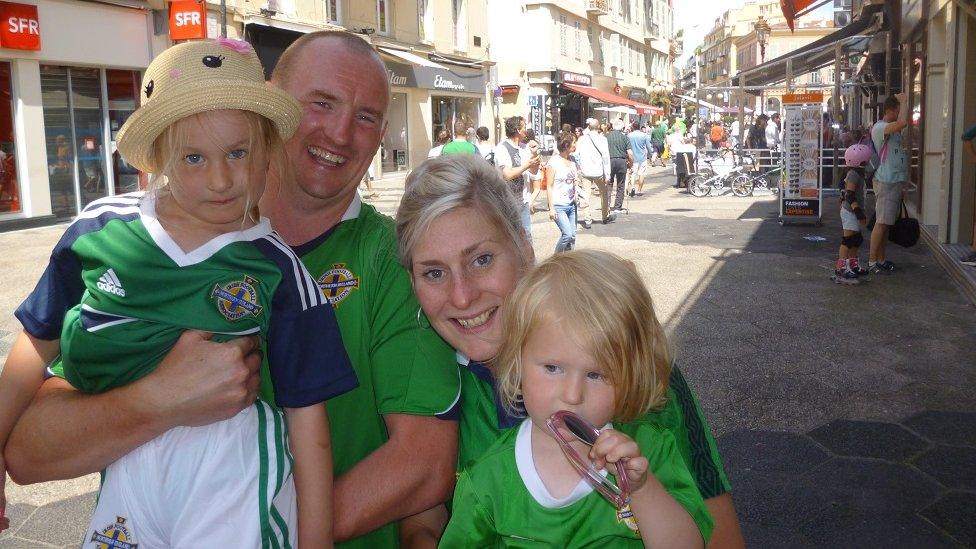

Catherine McComb has been waiting for three years to see a consultant

Haemochromatosis would usually be determined by a series of blood tests to detect high iron levels.

But Haemochromatosis UK says people are struggling to have the genetic blood test carried out.

It typically costs about £200 but the charity has funded 30,000 self-test kits for use by people in Belfast.

'I had to push for it'

Catherine McComb still considers herself one of the lucky ones because she was diagnosed with haemochromatosis before any damage was caused.

She gained her "hard-fought diagnosis" over three years ago.

Since then the 40-year-old has been "in limbo" waiting for an initial consultation to discuss her treatment plan.

Treatment includes regularly giving blood to lower the level of iron in the body.

Catherine says it's a "wonderful relief" to finally understand her condition

Catherine described her initial symptoms as feeling "generally under the weather".

She repeatedly contacted her GP before a locum doctor flagged abnormal blood iron levels.

"It was like day and night how much I had changed and I knew it wasn't just that I was getting older," she said.

"I had the self-awareness to push for an understanding."

What is the Celtic Curse?

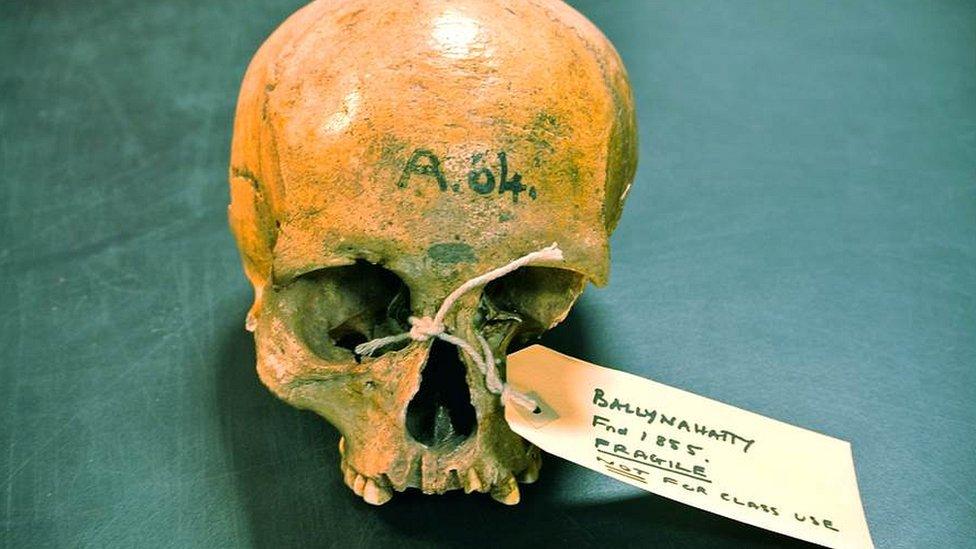

Excavated near Belfast in 1855, the Ballynahatty woman lay in a Neolithic tomb chamber for 5,000 years

The gene mutation that causes most cases of hereditary haemochromatosis is believed to have originated in the Celtic population of Europe.

It is most commonly found in people of Irish, Scottish, Welsh or Cornish ancestry.

DNA analysis of the genomes of a Bronze Age farmer on Rathlin Island in County Antrim showed that it was already established by that period.

Earlier still, the remains of a Neolithic woman found at Ballynahatty near Belfast show that she carried a different variant also associated with an increased risk of the disorder.

Read more: DNA sheds light on Irish origins

Three of the Sheridan siblings from Belfast have the condition, with 66-year-old Bill having recently been diagnosed.

"It's interesting because we're all at different stages," he said.

One of his sisters, aged 69, believed she had arthritis and fibromyalgia for 15 years before finally understanding the condition.

"Her doctor told her she quite possibly could have been misdiagnosed," said Bill.

Bill Sheridan and his two sisters have been diagnosed with the blood condition

"If people get tested early they could give blood and benefit the rest of society and not be a burden on the health service like my sister has been."

Bill and his siblings were all told they were "red-flag referrals" to see a specialist, later learning that could take two to three years, so they chose to pay for a private consultant.

"I don't know how many people are sitting waiting… when it's easily treatable with no cost to society," he said.

'Dad insisted we get tested'

Sean O'Hare, 52 from Forkhill in County Armagh, lost his father Tony to haemochromatosis-induced heart failure in 2018, having been diagnosed two years previously.

"He had signs of fatigue and joint pain but we'd have seen him as being really healthy for his age, active all his life," said Sean.

"He was a keen gardener and golfer who wouldn't have been a person for sitting around.

BBC News NI health correspondent Marie-Louise Connolly explains haemochromatosis

"My father insisted we get tested - he was a pharmacist himself."

Sean said they now knew of two carriers in the family.

"They don't actually test for haemochromatosis, you have to ask - that has to change," he said.

Since the passing of Sean's father, the family have been raising money to fund genetic testing in Newry this month.

"The big thing is about creating awareness - if it saves somebody's life it'll all be worthwhile."

How can I get tested?

First-degree testing - siblings, parents and children - was recommended by the British Society of Haematology in 2018.

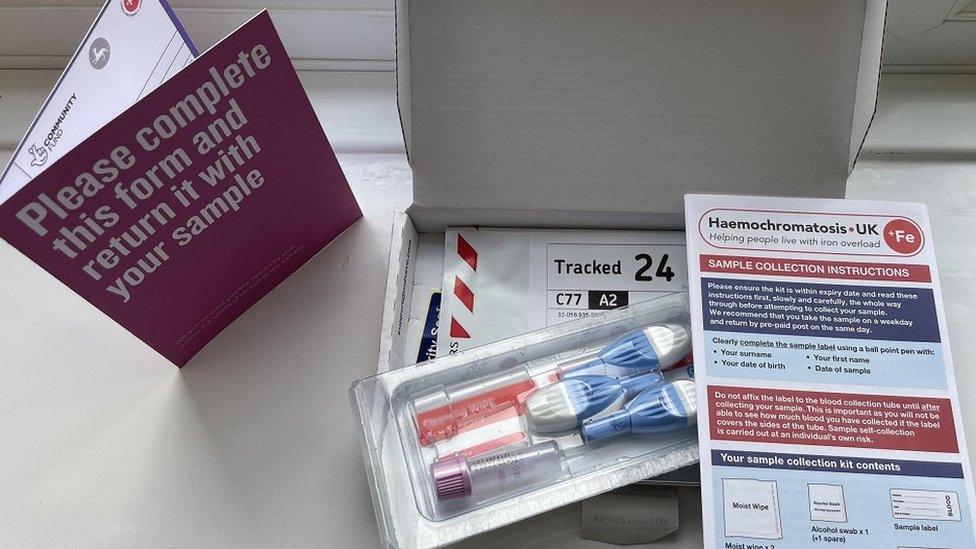

A recent campaign, funded by Haemochromatosis UK, has meant thousands of households in Belfast have been offered free self-test kits.

The resulting samples are posted to an NHS-accredited laboratory, which provides results within a fortnight.

Thousands of genetic self-test kits are being distributed across Northern Ireland

Similar schemes were piloted in Carrickfergus and Londonderry over the past two years.

Neil McClements from the charity said it has established that one in 10 people have the condition.

"They are all now receiving care, having previously been either unaware of their status or having been turned down for a test by their GP when a close relative was diagnosed," he said.

"UK guidance says first-degree relatives should all be screened if someone is diagnosed - this mostly doesn't happen in Northern Ireland for cost reasons."

"I understand we got it from the Vikings," said my nurse said as she extracted blood from me last week.

I am being tested for haemochromatosis after several family members were diagnosed.

We discovered it was in our family in 2017 - back then I had never heard of the disorder referred to as the "Celtic curse".

For centuries people in Ireland lived with it, unaware they had it - did that do them any harm?

My feeling is that it's better to know because then you can do something about it.

There are now more cases being diagnosed as people like me are asking to be tested.

Those affected in my family have changed their diet.

Some breakfast cereals are avoided, as are other iron-loaded foods and certain alcoholic drinks.

Regular venesections - collecting blood for diagnosis - mean their iron counts are going down.

During family get-togethers discussion often turns to "haemo" and comparing iron counts. I await my result.

Related topics

- Published17 January 2019

- Published2 March 2018