Ancient DNA sheds light on Irish origins

- Published

Scientists have sequenced the first ancient human genomes from Ireland, shedding light on the genesis of Celtic populations.

The genome is the instruction booklet for building a human, comprising three billion paired DNA "letters".

The work shows that early Irish farmers were similar to southern Europeans.

Genetic patterns then changed dramatically in the Bronze Age - as newcomers from the eastern periphery of Europe settled in the Atlantic region.

Details of the work, by geneticists from Trinity College Dublin and archaeologists from Queen's University Belfast are published in the journal PNAS, external.

Team members sequenced the genomes of a 5,200-year-old female farmer from the Neolithic period and three 4,000-year-old males from the Bronze Age.

Opinion has been divided on whether the great transitions in the British Isles, from a hunting lifestyle to one based on agriculture and later from stone to metal use, were due to local adoption of new ways by indigenous people or attributable to large-scale population movements.

The ancient Irish genomes show unequivocal evidence for mass migration in both cases.

Wave of change

DNA analysis of the Neolithic woman from Ballynahatty, near Belfast, reveals that she was most similar to modern people from Spain and Sardinia. But her ancestors ultimately came to Europe from the Middle East, where agriculture was invented.

The males from Rathlin Island, who lived not long after metallurgy was introduced, showed a different pattern to the Neolithic woman. A third of their ancestry came from ancient sources in the Pontic Steppe - a region now spread across Russia and Ukraine.

"There was a great wave of genome change that swept into [Bronze Age] Europe from above the Black Sea... we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island," said geneticist Dan Bradley, from Trinity College Dublin, who led the study.

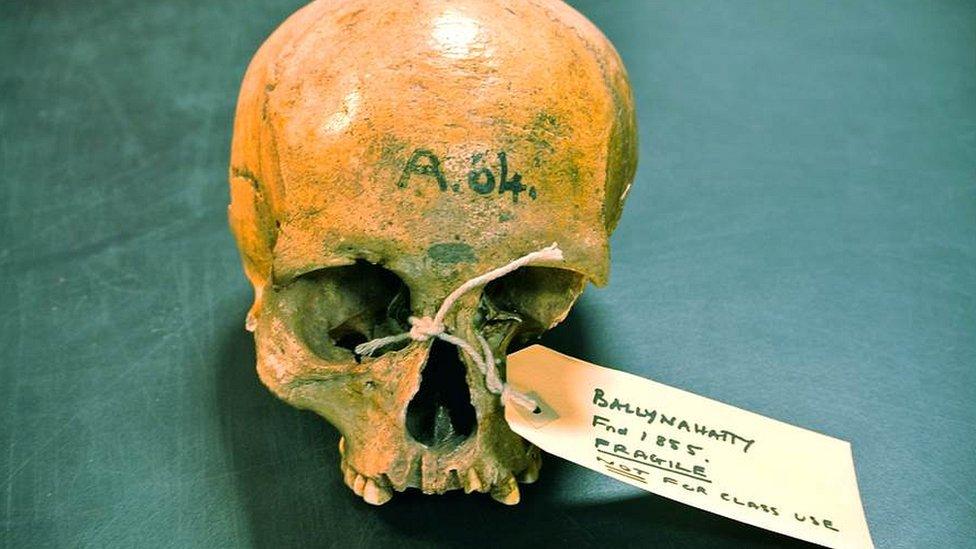

Excavated near Belfast in 1855, the Ballynahatty woman lay in a Neolithic tomb chamber for 5,000 years

Prof Bradley added: "This degree of genetic change invites the possibility of other associated changes, perhaps even the introduction of language ancestral to western Celtic tongues."

In contrast to the Neolithic woman, the Rathlin group showed a close genetic affinity with the modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh.

"Our finding is that there is some haplotypic [a set of linked DNA variants] continuity between our 4,000 year old genomes and the present Celtic populations, which is not shown strongly by the English," Prof Bradley told BBC News.

"It is clear that the Anglo-Saxons (and other influences) have diluted this affinity."

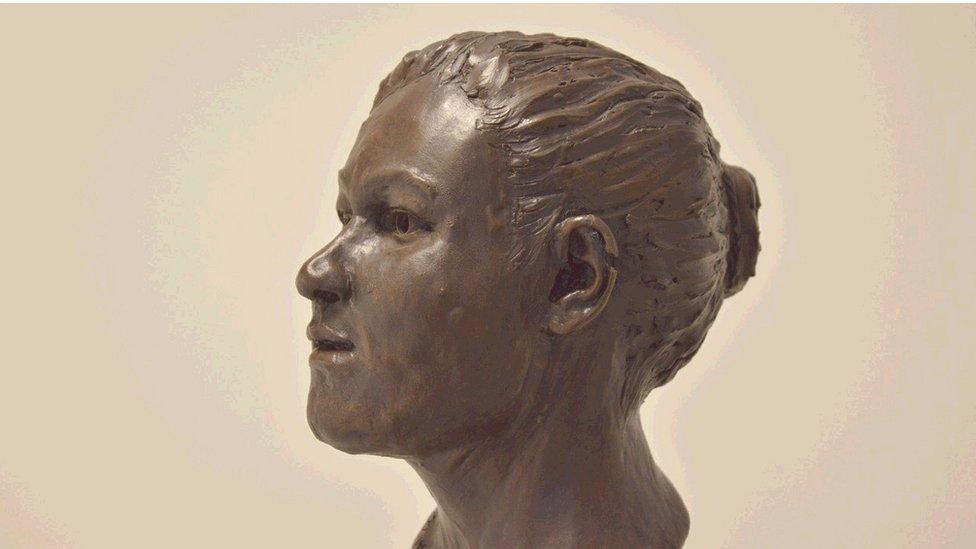

A reconstruction of the Ballynahatty Neolithic skull

Today, Ireland has the world's highest frequencies of genetic variants that code for lactase persistence - the ability to drink milk into adulthood - and certain genetic diseases, including one of excessive iron retention called haemochromatosis.

One of the Rathlin men carried the common Irish haemochromatosis mutation, showing that it was established by the Bronze Age. Intriguingly, the Ballynahatty woman carried a different variant which is also associated with an increased risk of the disorder.

Both mutations may have originally spread because they gave carriers some advantage, such as tolerance of an iron-poor diet.

The same Bronze Age male carried a mutation that would have allowed him to drink raw milk in adulthood, while the Ballynahatty woman lacked this variant. This is consistent with data from elsewhere in Europe showing a relatively late spread of milk tolerance genes.

Prof Bradley explained that the Rathlin individuals were not identical to modern populations, adding that further work was required to understand how regional diversity came about in Celtic groups.

"Our snapshot of the past occurs early, around the time of establishment of these regional populations, before much of the divergence takes place," he explained.

"I think that the data do show that the Bronze Age was a major event in establishment of the insular Celtic genomes but we cannot rule out subsequent (presumably less important) population events contributing until we sample later genomes also."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

- Published8 October 2015

- Published2 March 2015

- Published17 September 2014

.jpg)

- Published10 October 2013