Good Friday Agreement: Prisoners, pain and the price of peace

- Published

Patrick Magee (middle), who was jailed for attempting to kill then PM Margaret Thatcher in the Brighton bombing, was one of hundreds of paramilitary prisoners released early under the Good Friday Agreement

It is almost 25 years since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the peace deal that brought an end to the Troubles - BBC News NI, across our news website, TV and radio, has been looking back at the historic deal, speaking to the key players and reflecting on how the agreement continues to shape Northern Ireland.

The early release of paramilitary prisoners, many of whom emerged to scenes of jubilation outside prison gates, was one of the most controversial aspects of the peace deal. More than 400 prisoners were released in the two years after it was signed.

For many, this process was painful and distasteful, for others a necessary evil or part of the path to peace - and, as former BBC security correspondent Brian Rowan writes, it is a process that has left many unanswered questions all these years later.

It was the issue that could have broken the back of the Good Friday Agreement.

And, 25 years on, people are still hurting.

You hear it in the voice and in the words of the retired prison officer Dessie Waterworth, who speaks with 35 years of experience - 20-plus of those years, including in the conflict period, working inside the Maze Prison through to its closure.

He describes the republican and loyalist celebrations of prisoner releases as obscene.

And you hear the hurt in his telling of how he spoke to Tony Blair back in 1998 - when he accused the then prime minister of walking on the graves of soldiers, police officers and prison officers.

Peace is not easy; the compromises of '98 not fair in the eyes of some.

Good Friday Agreement: 'I told Tony Blair he was walking on officers' graves'

By the late 1990s, the prisoners of the Maze had become part of a political negotiation - part of the making of the Good Friday Agreement.

They had influence, and, as talks progressed, became the conscience of negotiators and leadership groups outside, as people who could not - and would not - be left behind.

Beyond Good Friday, the hundreds of releases were phased over a two-year period and, we know now, that you can't have peace with prisoners.

This is something I spoke about with Gary Mason - a Methodist minister whose work has been on the interfaces of Belfast, along those peace lines and frontlines that still divide communities.

"First of all, you would never have got over the line," he said, meaning an agreement would not have been possible without the prisoner release element.

Methodist minister Gary Mason believes an agreement would not have got over the line without the release of prisoners

"But even if you had got over the line, that ghost was always the shadow looking over this space," he continued.

"So, it was crucial that they [the prisoners] were part of it, painful and difficult as it was."

When I read my diary - back to March 1998 - I find a first reference to a possible commission to address this issue.

My diary note reminds me of interviews with Gerry Kelly of Sinn Féin and the loyalist Billy Hutchinson - this a first exploration of what a process might look like.

Both rejected the idea of a commission and said the UK government should act.

Good Friday Agreement: Gerry Kelly and Billy Hutchinson on prisoner release in 1998

Recently, in a special edition of the republican magazine An Phoblacht to mark the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, the former Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams wrote of the last hours of negotiations inside the Castle Buildings talks venue on the Stormont estate.

"We wanted the prisoners out within a year. However, two years was our private fall-back position. The Brits wanted three years."

Understandably, this was one of the last issues to be settled; an indication of just how raw and emotive it was, and still is.

If prisoner release had been set at one year, as republicans wanted, the talks could have collapsed. The agreement could have been lost.

Negotiation is being able to see beyond your own needs and demands - understanding what is possible, and what is not.

You have to think about others.

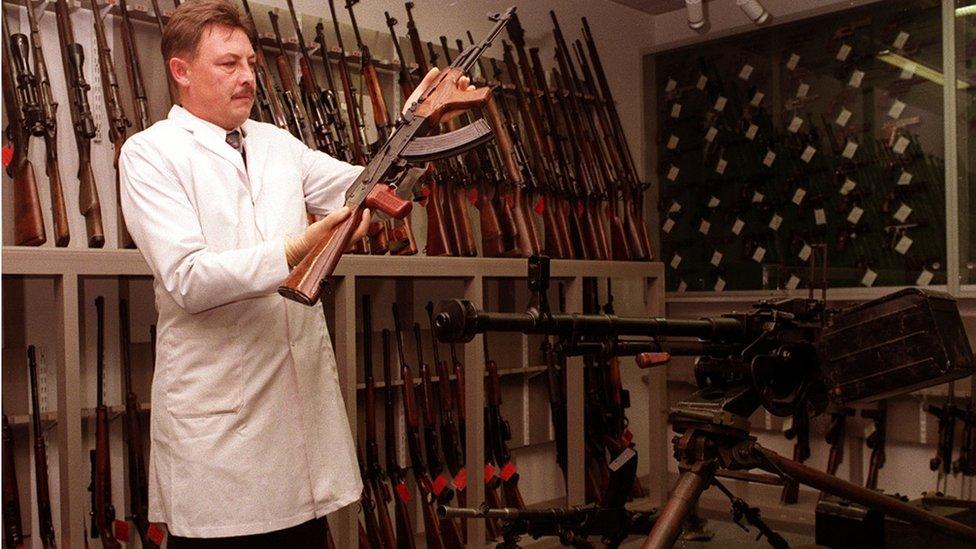

The prison itself would later become a big part of the story - what should remain of it and for what purpose.

Read more of Brian Rowan's reflections on the Good Friday Agreement:

Need more information of what the agreement was?

There was a plan for some retained buildings to become a museum and a peace centre, but that conversation was poisoned by the argument that it would become a "shrine" to the dead of the republican hunger strike of 1981.

There are those who still speak of ghosts in the grounds of the Maze, and who want its remaining buildings bulldozed. But you can't bury history.

Good Friday Agreement: Maze could be 'retained for prison staff'

A former director general of the Prison Service, Robin Masefield, could see other possibilities.

He told me parts of the Maze could be retained "for prison staff and their families and for the next generation where we could have taken people and said that was our side of it".

Twenty-five years after Good Friday, there is still no process to put the conflict period to rest.

The Maze Prison closed in 2000

The Maze is a big part of that story.

And there is no such thing as throwing away the keys - not on memory, and history and its telling.

The past, the prison and the prisoners - all still part of the present.

Declan Harvey and Tara Mills explore the text of the Good Friday Agreement - the deal which heralded the end of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

They look at what the Agreement actually said and hear from some of the people who helped get the deal across the line.

Click here to listen to the full box set on BBC Sounds.

TROUBLES AND PEACE: A story of history and hope - 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

ENDGAME IN IRELAND: The inside story of the peace process in Northern Ireland.

Related topics

- Published20 February 2023

- Published2 March 2023

- Published3 April 2023