Good Friday Agreement: Prisoner release a bitter pill for victims

- Published

"It leaves a bad taste in your mouth" - the killer of June McMullan's husband served two years because of the Good Friday Agreement

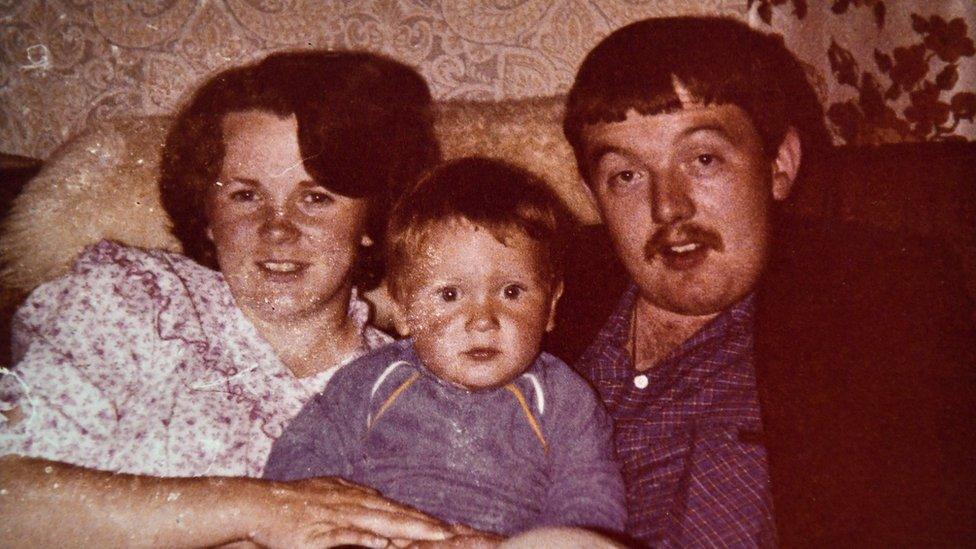

Off-duty policeman John Proctor was shot dead in the grounds of a hospital, where he had just been to visit his wife and newborn son.

His widow June, in the hospital with their second child, heard the gunfire.

"He was riddled from top to bottom with 17 bullets and as he lay dying on the ground they stepped over him and finished it," she says.

The killer was handed a life sentence but because it happened in Northern Ireland during the Troubles he only had to serve two years.

The release of paramilitary prisoners was one of the consequences of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which brought an end to 30 years of bloodshed.

It was probably its most controversial aspect.

June, pictured with John and their eldest son, heard the gunfire that killed her husband

It meant cells at the Maze Prison, near Belfast, emptied of more than 400 inmates, both republican and loyalist, who had been responsible for some of the acts of violence which cost 3,500 lives during the Troubles.

The legislation that enabled their early release still remains in place, meaning most people who are convicted today of a Troubles-era offence can apply to be let out after two years of their sentence.

It is what happened in the case of Constable Proctor, a father-of-two.

The 25-year-old was murdered in 1981 at the Mid Ulster Hospital in Magherafelt, County Londonderry, by the IRA.

His family waited 30 years for an investigative breakthrough and it finally arrived when advances in forensics identified DNA on a cigarette butt recovered from the murder scene.

In 2013 Seamus Kearney was convicted of murder and sentenced to life.

Constable Proctor's widow, who has since remarried and is now June McMullan, says she was prepared for his early release.

But it didn't make it any easier to accept as she faced Kearney across a courtroom.

"Our government was wrong for going down that road" - June is critical of the early release policy

"It was a bad taste in your mouth knowing he was only going to do two years," she says.

"That was the small print on the agreement and I think that was wrong.

"It's still sick to think a life was only worth two years.

"If you were in England and you killed a policeman you would do a bit more than two years.

"For the victims our government was wrong for going down that road."

Hundreds freed

In 1998 prisoners had become important to securing the peace deal and helping ensure that it stuck.

A condition to prisoners being freed - technically they are out on a licence which could be revoked - was that they be affiliated to organisations that maintain their ceasefires.

One of the Maze Prison's H-blocks - the prison has been empty since its closure in 2000

Also they must not re-engage in terrorism or they face being returned to jail to serve out sentences in full.

The body that deals with releases, the Sentence Review Commissioners, says that as of last month a total of 483 prisoners have been freed.

The overwhelming majority of them in the two years which came after the agreement in 1998.

Only 27 prisoners have been returned to jail for breaching conditions.

Read more on the agreement

EXPLAINER: What is the agreement?

ANALYSIS: Is it still fit for purpose?

VIDEO: The agreement in 90 seconds

Thomas Quigley was sentenced to serve no less than 35 years for the 1981 Chelsea Barracks bombing in London.

Two people were killed and 40 injured when IRA bombers targeted a bus carrying soldiers.

He recalls being dazzled by the lights of television cameras as he emerged from prison in 1999 after 18 years behind bars, barely believing his release was happening.

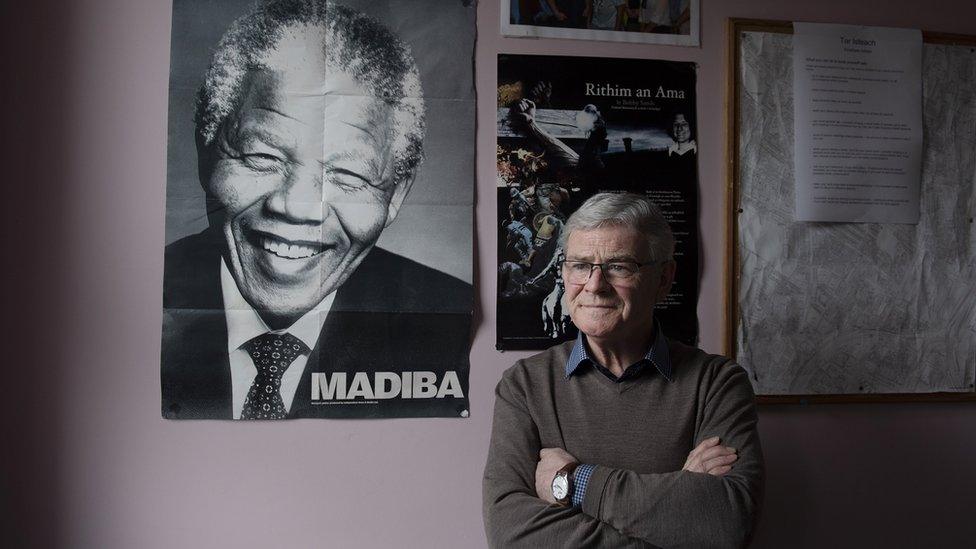

"I can't imagine the republican movement signing up without prisoner releases" - Thomas Quigley

He had been relocated from a prison in England to the Maze, or Long Kesh as republicans call it, at the time of the first IRA ceasefire in 1994.

"I was relieved that the conflict was over and there was going to be peace - the fact I was released reinforced that," says the 67-year-old.

"I can't imagine the republican movement would have signed up to the agreement if there hadn't been prisoner releases."

Referencing the death of his brother, an IRA member who was shot by the Army in Belfast in 1972, he adds: "I completely understand how people felt their loss because we had lived it ourselves.

"We are now living in a far safer society and there are people here today who wouldn't be if the conflict had been allowed to continue."

'The bigger picture'

Fiona Kelly remembers holding her 10-month-old daughter in her arms at the time the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

Like the vast majority of people on both sides of the Irish border she voted in favour of it in the referendum that followed.

She says she endorsed it for the good of future generations but adds that it came with a price.

"It was a bitter pill to swallow and still is" - the murderer of Fiona Kelly's father was released five years into 12 life sentences

Her father Gerry Dalrymple, 58, was a Catholic joiner and one of four people murdered in a gun attack carried out on a work van by the Ulster Defence Association at Castlerock, County Londonderry, in 1993.

One of those involved, Torrens Knight, was freed five years after being given 12 life sentences, one for each of the murders at Castlerock and eight others at a pub in Greysteel nearby.

"He is a free man and we are still left to carry the pain every day of what he did to our family," says Mrs Kelly.

"It was a bitter pill to swallow and still is.

"We wanted an end to the violence. It would have been selfish of me not to have looked at the bigger picture of what the agreement involved."

A continuing legacy

Twenty-five years after the agreement, another set of bereaved families and victims find themselves being asked to compromise on justice.

This time in respect of about 1,200 unsolved killings and the perpetrators who have never been charged.

The Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill looks like passing into law before the summer.

Under it the government will offer conditional amnesties to murder suspects who co-operate with a new independent body tasked with fact-finding.

Information on cases will be gathered and families will receive reports.

But there will be no more police investigations related to the Troubles anywhere in the UK, nor will there be inquests or civil actions.

The legislation's roots are in a government manifesto pledge in 2019 to protect Army veterans from future prosecutions.

It is opposed by all victims' groups in Northern Ireland and all its political parties.

Having unlocked prison cells in 1998 the courtroom doors now look set to be shut on the Troubles in controversial fashion.

Declan Harvey and Tara Mills explore the text of the Good Friday Agreement - the deal which heralded the end of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

They look at what the agreement actually said and hear from some of the people who helped get the deal across the line.

Listen to all episodes of Year '98: The Making of the Good Friday Agreement on BBC Sounds.