Erosion: Researchers map Northern Ireland's changing coastline

- Published

- comments

For the first time, how the entire coastline of Northern Ireland is changing has been mapped by researchers at Ulster University.

The team studied almost 200 years' worth of maps, surveys and photographs to determine the extent of erosion.

Each 25m (82ft) section of coastline was examined for positional changes.

Researchers looked at how human modification advanced the shoreline by reclaiming land and building power stations, harbours and ports.

The information will help shape how coastlines are managed as well as identifying those areas most vulnerable to coastal change.

The group began with the first detailed Ordnance Survey maps of Northern Ireland, dated circa 1830, and worked through to the present day with a recent coastal topographic LiDAR (light detection and ranging) survey.

The year-long project was led by Prof Derek Jackson and funded by the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (Daera).

Prof Jackson described it as "a huge technical challenge".

"But in the end it has produced a fantastic database from which to better understand how the Northern Ireland coastline has changed over historical times," he said.

"For the first time Northern Ireland now has a detailed picture of how dynamic, particularly the sandy stretches, of the coastline are.

"This gives a much better scientific basis from which to manage these sites in the future."

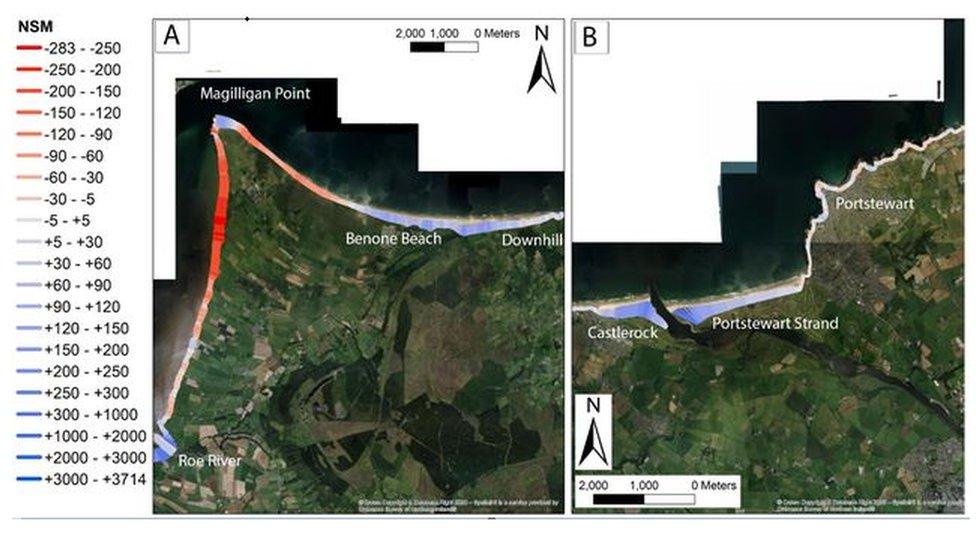

The largest natural shoreline erosion levels were recorded on the western side of Magilligan Point in County Londonderry.

The largest shoreline advancement over the last two centuries was identified at Murlough near Newcastle in County Down.

The researchers found human activity two centuries ago had played a major role.

"The largest shoreline advancements recorded in the last two centuries along the Northern Ireland coastline were all induced by human modifications, mainly during the 19th century," said Prof Andrew Cooper, co-investigator on the project.

Those modifications included extensive land reclamation in sea loughs, construction or expansions of ports and harbours, power stations, wastewater treatment areas or touristic facilities.

Rocky coasts, apart from limited rockfalls, were less subject to large-scale changes as were shorelines not influenced by human modifications in sea loughs.

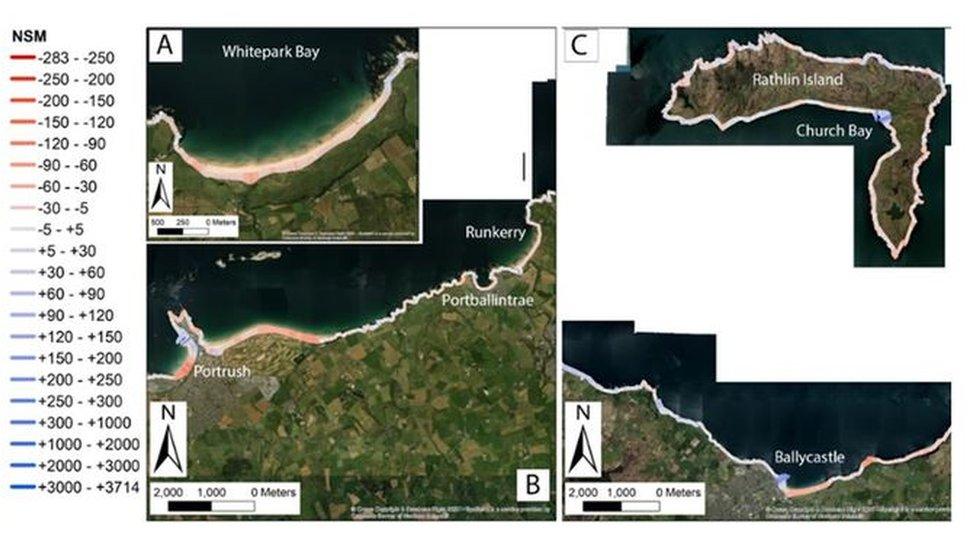

Varying levels of erosion were found along open-coast sandy shorelines.

But there was build-up at the Castlerock-Portstewart Strand complex.

That was due to the extensive jetties at the River Bann entrance which are trapping sand from both directions.

Similar build-up at Ballykinler in County Down was linked to local geology and inlet exchanges between the inner and outer Dundrum Bay.

The project was undertaken to help address the lack of scientifically-robust data about how the coastline is changing.

It is one of a series of initiatives undertaken by Daera through the Northern Ireland Coastal Forum and the associated working group.

Daera says it is working closely with the statistical ESRI Ireland to make all the information publicly available via the Northern Ireland Coastal Observatory.

Related topics

- Published12 November 2015

- Published6 March 2015