Northern Ireland state papers: 9/11 and moving Wimbledon FC to Belfast

- Published

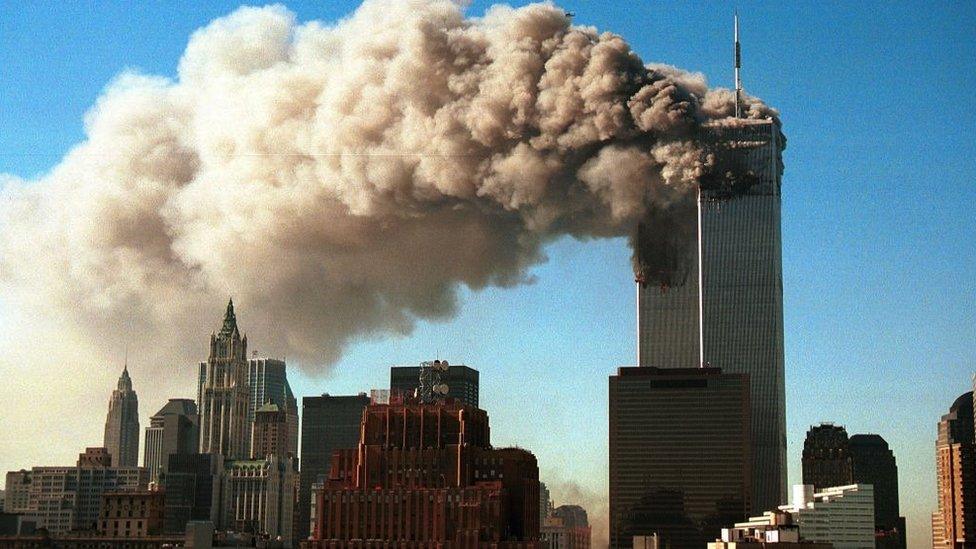

Hijackers crashed two airliners into the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001

The biggest news story of 2001 was the 11 September terrorist attacks in New York and Washington.

And, as newly-released state papers from the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) show, they had far-reaching implications.

One file shows that there were concerns about the likely impact on the economy.

Within weeks of 9/11, British Airways cancelled its Heathrow to Belfast Aldergrove route and 30,000 fewer US visitors to NI were expected for 2002.

The file also said that up to 1,600 redundancies were anticipated in Bombardier Aerospace in Belfast.

The potential for wider terrorist threats was considered most likely to come from chemical or biological attacks - "the main risks identified here are anthrax, smallpox, botulism and nerve gases such as sarin", the file said.

Greater scrutiny was expected of the destination of EU structural funds that were allocated to groups which included ex-prisoners with paramilitary backgrounds.

The latest release of state papers from the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland covers the years between 1997 to 2001.

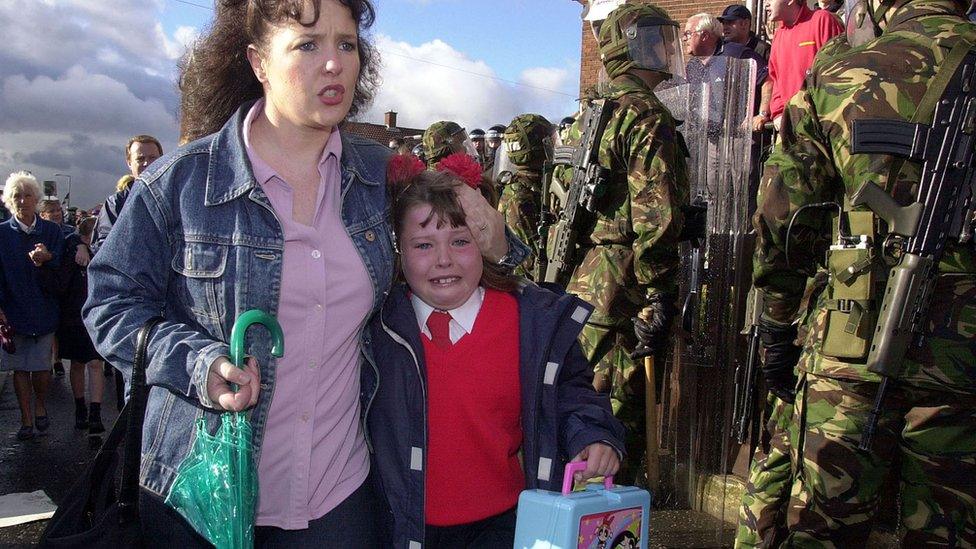

A surprising absence from the files from 2001 is any reference to the stand-off at Holy Cross Primary School in Ardoyne, north Belfast, in contrast to the extent of coverage in the recently released files from the National Archives of Ireland, released on Wednesday.

Some of the schoolgirls were said to be traumatised by the violent protests

These might yet come in subsequent releases or the gap might reflect the reserved status of justice and security matters at the time.

A number of issues which remain current today are reflected in files dating back over 25 years.

The question of providing a national football stadium was discussed in 1997 as part of the proposed relocation of the Premiership side Wimbledon FC to Belfast, to be renamed Belfast United.

Ronnie Spence, the then permanent secretary of the Department of the Environment, hoped that a Belfast-based team would "be able to build up strong cross-community support".

'The passion never dulls'

His optimism that the city's reputation would be enhanced by association with a team "performing at the top level in English and European competitions" was viewed as "a brave prediction" by his counterpart in the Department of Economic Development, Gerry Loughran, who noted Wimbledon's mid-table status in the Premiership and failure to qualify for European competitions.

Tensions between both men did not quite reach fever pitch though Loughran, recommending the writings of Nick Hornby to Mr Spence, was sceptical that local football fans would transfer their allegiances from English and Scottish teams.

These were "bonds for life" in which "the passion never dulls".

Then Northern Ireland secretary, Mo Mowlam was also dubious about a proposal she did not think was "particularly safe", although Prime Minister Tony Blair thought "it would be excellent if Wimbledon were to move to Belfast".

Tony Blair, centre, with Northern Ireland Minister Paul Murphy and Secretary of State Mo Mowlam

Dr Mowlam and Mr Blair were also at odds in 1998 over her desire to consider reform of Northern Ireland's law on abortion.

It was proposed to establish an independent review panel, chaired by the Lord Chief Justice to "inquire into the legal, medical and social issues" surrounding abortion law and practice in Northern Ireland and also to explore "related issues including sex education, access to counselling, and support services for pregnant women".

Dr Mowlam's proposed review was vetoed by the prime minister who advised putting it "on ice for now", in view of the likely lack of "scope for bi-communal support for a change to the law".

On the domestic political scene, the processes governing the newly-established assembly were still evolving in 1999.

Peter Robinson, then deputy leader of the DUP, objected to a proposed extension to the Ministerial Code of Conduct which he interpreted as having "more to do with gaining control by the centre and in particular the first and deputy first ministers over ministerial colleagues", reflective of what he saw as "an unhealthy addition to empire building and authoritarianism".

Lough Neagh: Why has the UK's largest lake become green and toxic?

The risk of pollution to Lough Neagh is the subject of a file dating back to the 1950s, when there was a proposal to locate a nuclear power plant there.

The Nobel Physics laureate John Cockroft, of the UK's Atomic Energy Authority, advised Northern Ireland's prime minister, Lord Brookeborough, against siting it at Lough Neagh.

The increasing reliance on Lough Neagh as a source for Belfast's water supply made the authority "considerably less happy about the choice of Lough Neagh for a nuclear power station site".

Although Mr Cockroft was confident that no "radiological hazard would result from normal operation of the power station… the possibility of an accident leading to over-heating… and some release of radioactive products" was too great a risk.

The warning came only 10 months after the UK's most serious nuclear accident, a fire at the Windscale (now Sellafield) plant in Cumbria in October 1957.

This undoubtedly made the Atomic Energy Authority more risk averse, but it also raises the question of whether a nuclear power station would have been built at Lough Neagh if Windscale had not happened.

Professor Marie Coleman is Professor of Twentieth Century Irish History at Queen's University Belfast

- Attribution

- Published28 December 2023

- Published19 July 2023