'Dogs in the street know Scappaticci is Stakeknife'

- Published

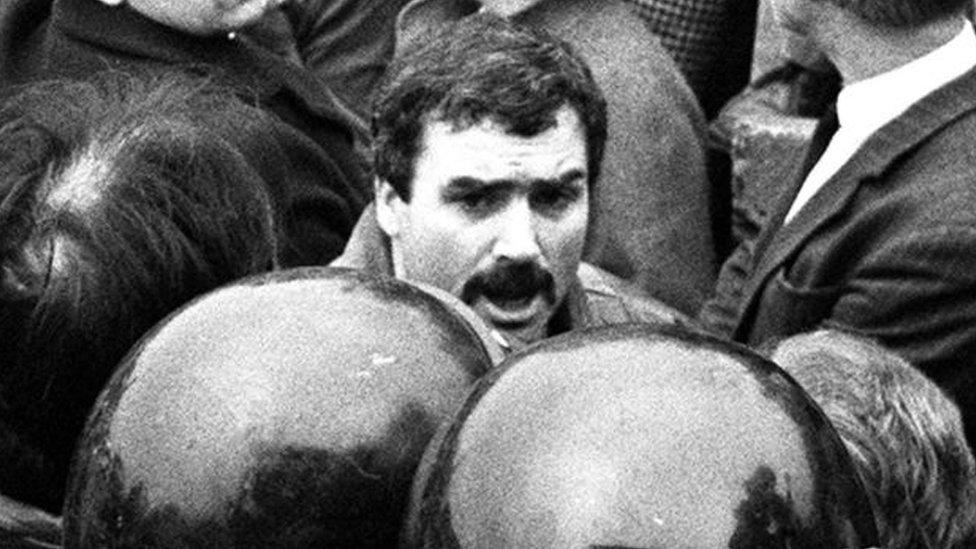

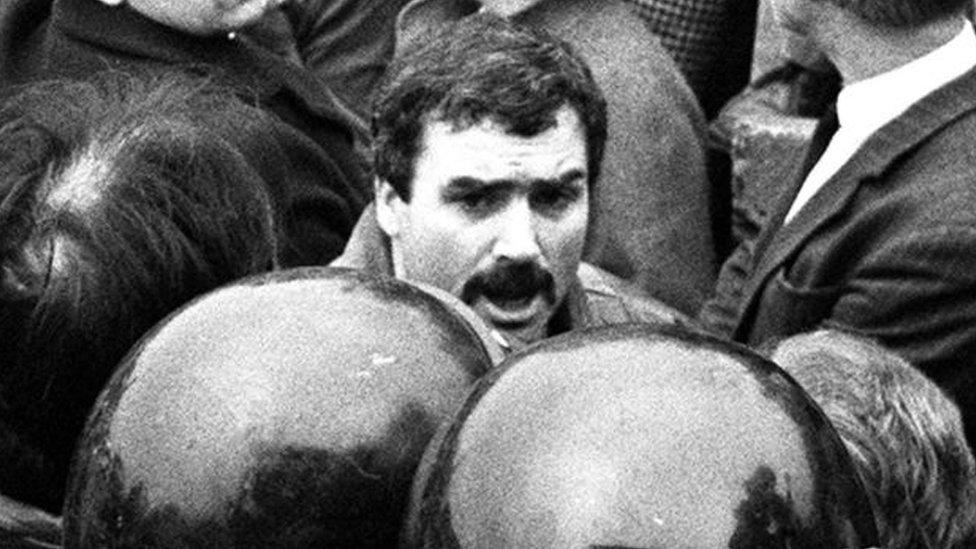

Freddie Scappaticci always denied he was an Army agent within the IRA

There are many sins in the story of 'Stakeknife', and many questions that wait for answers. On Friday, the interim report of Operation Kenova will be published - an investigation established in 2016 under the command of then Bedfordshire Chief Constable Jon Boutcher, who now holds the most-senior rank in the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

His task was to probe the activities of an alleged Army agent - an investigation that would shine a torch not just on the military and MI5, but inside the IRA.

As Brian Rowan, BBC News NI's former security editor, now writes, there is "a truth" that could bring the roof down, but will it ever be told in all of its ugly detail?

"The dogs in the street know that Fred Scappaticci is the agent Stakeknife," says Belfast lawyer Kevin Winters.

In the spring of 2003, I came face-to-face with 'Stakeknife' - with Fred Scappaticci.

It happened after he had been in hiding for some days; forced to run and chased by headlines calling him an agent.

He would have known the consequences.

For years he had run internal IRA interrogations, at a time when he was also working for the Army.

Back in May 2003 he left his home and, then, came back to deny the allegation.

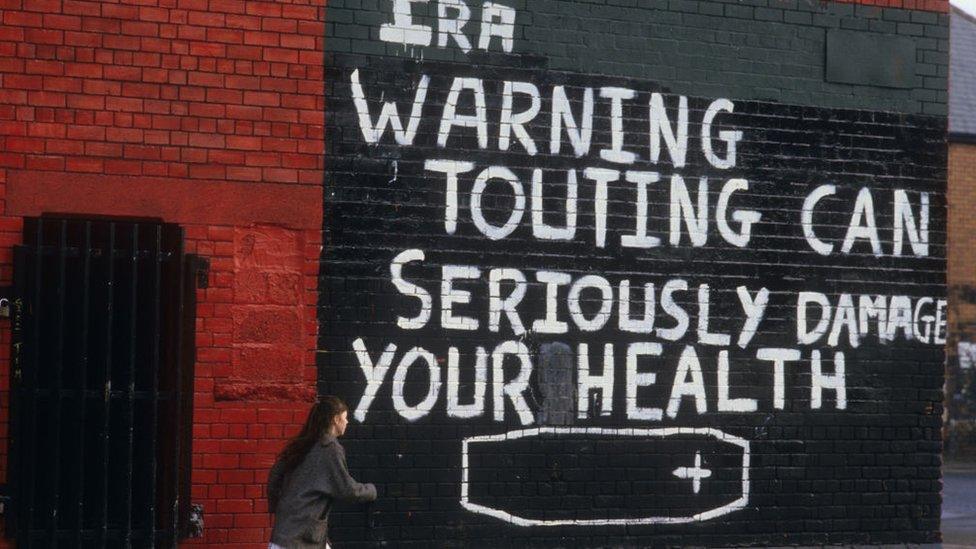

But the scandal of Stakeknife is this; that for years, an Army agent operating inside the IRA was employed and paid in a role that involved him culling that organisation of other suspected agents.

The bodies on the border, and elsewhere, sometimes almost naked and with hands and feet bound, tell the stories of what happened next.

The Army, and others in that intelligence community, cannot in any credible way deny knowledge of his role and actions.

This case crossed every line.

On Friday, Operation Kenova, a seven-year police investigation costing about £40m, will produce an interim report.

And, I am told that we can expect to read something about apologies on Friday - that the report will ask for these.

What might that look like?

From the UK government, an apology for what could have been prevented, and from republicans, an apology for IRA murders and for how families were intimidated and ostracised.

I believe that the IRA acquiesced in Scappaticci's denial to manage him and them out of a predicament.

Will the interim Kenova Report definitively name Scappaticci as Stakeknife?

There are fears that it won't; concerns shared by the Belfast lawyer, Kevin Winters.

"Many people will be sceptical if Kenova cannot name Fred Scappaticci as Stakeknife,' he says.

"They will with good reason query the use of NCND [a longstanding policy used to neither confirm nor deny sensitive information] to prevent naming him."

I am hearing that Jon Boutcher wants a review of that NCND policy, and that we can expect to read more about that on Friday.

Would such a review allow for a conclusive statement in the final report that Scappaticci was Stakeknife?

And would it enable the Kenova team to give more information to families?

Grafitti in Belfast warned of the dangers of informing on the IRA

Scappaticci is dead now, adding to the argument that he should be named now as the agent Stakeknife and that the NCND policy should "be set aside" - "especially after a cost of £40 million," Mr Winters argues.

"This will compound families' disappointment after all the recent PPS decisions not to prosecute anyone.

"The dogs in the street know that Fred Scappaticci is the agent Stakeknife. That cost nothing."

In my reporting years at the BBC, I experienced how Northern Ireland's then police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), "set aside" this policy to neither confirm nor deny the identity of informers.

It happened in the summer of 1990, when the IRA killed Patrick Flood.

The Derry man's body was found at the side of a border road in County Armagh.

The RUC gave me its policy position, but later guided me in an unattributable briefing that Flood was not an informer - "emphatically not".

The source said that he would "never, never, never try to play games with [me]".

Follow-up newspaper coverage described both an "unprecedented denial", and a challenge to IRA claims that "is unique in recent years".

Scappaticci may well have been stood down from the IRA's internal security unit months before that "execution", as it was described.

Why did IRA give Scappaticci benefit of the doubt?

Many years later, and before that organisation had formally ended its armed campaign, Scappaticci, unlike Patrick Flood, was given the benefit of the doubt by the IRA.

The question is why?

Was it because of the political negotiations that stretched across 2003, from spring into the autumn, in an effort to restore Stormont?

Or was it because of the rank and role that Scappaticci once had within the IRA?

To shoot him (as so many others were shot) would have been to accept that the internal security of the organisation had been completely compromised, and that would have opened the door to another question: If him, then who else?

In many senses, he was too big a problem for the IRA to deal with.

At the time, Gerry Kelly of Sinn Féin accused "securocrats" of an extensive briefing of British and Irish journalists, and said "there was a clear need for full disclosure of the activities of these faceless and unaccountable agencies".

Years later, a one-time senior IRA figure told me that it would be safe to say that Scappaticci was in close contact with the republican leadership before that meeting I had with him in 2003.

And his assessment was this: that the leadership had decided to go along with the denial and to deal with it later down the road.

Freddie Scappaticci left Northern Ireland when identified by the media as Stakeknife in 2003

Will the Kenova report say anything about Scappaticci's contacts with the IRA in Belfast when he came out of hiding in 2003?

I don't know the answer to that question.

He told me then, that he had had no involvement with the republican movement for 13 years.

A confirmation of sorts that he had been stood down, under suspicion, in 1990, after the security forces rescued another agent from an IRA interrogation.

For years before then, Scappaticci (the Army's man) was part of another faceless and unaccountable team that ran the IRA's so-called "courts".

This is the ugliness of the truth.

Jon Boutcher is now the chief constable of the PSNI

Jon Boutcher arrived in Belfast in 2016 to lead the Operation Kenova investigation. He now holds the top job at the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

As the lead officer for Kenova in 2016, in his first news conference, he said this: "My principal aim in taking responsibility for this investigation is to bring those responsible for these awful crimes, in whatever capacity they were involved, to justice."

There will be no prosecutions.

The truth and lies of Stakeknife will not be tested in court.

Fred Scappaticci was Stakeknife - and this I am told is the only conclusion you can arrive at in the reading of this interim report.

He was a jigsaw piece in a much bigger picture that has not yet been made - just one of many agents.

In the numerous legacy consultations and negotiations here, how we remember the past has always been a part of the conversation.

And, I am hearing that a "day of reflection", first developed by the Healing Through Remembering project in 2007 and, then, supported, two years later, by the Consultative Group on the Past (Eames/Bradley), will again feature in the Kenova Report.

There is a lot to think about. And so much we still don't know, especially when it comes to the so-called 'dirty war'.

Related topics

- Published5 March 2024

- Published7 March 2024