Fighting to stay British: The strange history of the Ulster Covenant

- Published

Thousands of Ulster Volunteers line up to protest against Home Rule

The United Kingdom teetered on the brink of civil war, armed militias paraded and the British army threatened mutiny... not in an episode from the distant past but in a fairly modern crisis.

The event that triggered that crisis - the signing of the Ulster Covenant - took place just 100 years ago, on 28 September 1912.

The centenary is being marked with exhibitions, parades and church services across Northern Ireland.

Oath in defiance

The Ulster Covenant was an oath in defiance of the British Government, signed by nearly a quarter of a million men of Ulster, Ireland's northernmost province.

But it was no breakaway movement. On the contrary, they wanted Ulster to remain part of the United Kingdom and were prepared to fight to keep it there.

The long and often bitter history between Britain and Ireland had witnessed many attempts by the Irish people to establish control over their own affairs. By the late 19th century, the favoured formula was 'Home Rule' - a devolved parliament in Dublin to legislate on Irish-only issues, but with Ireland still part of the British Empire.

Not everyone in Ireland favoured Home Rule. Opposition among the self-styled 'unionists' was fierce, particularly in Ulster, where the mainly Protestant population feared it was a first step to an independent Ireland. For them, Home Rule meant 'Rome rule', with the Roman Catholic, rural south dominating the Protestant, industrial north.

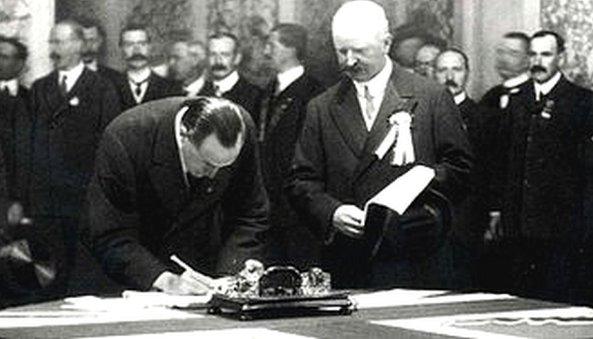

Edward Carson is first to sign the Ulster Covenant at Belfast City Hall, 28 September 1912

Striking the bargain

The driving force behind Home Rule was in fact a Protestant landowner called Charles Stewart Parnell, whose Irish Parliamentary Party brought devolution to the very top of the British political agenda.

Home Rule bills were defeated in 1886 and narrowly in 1893, but the movement was growing in strength and it was felt by many that it was only a matter of time before there was a parliament in Dublin.

In 1910, the question once again loomed large. The two British general elections of that year had both produced hung parliaments. The Liberals remained the largest party, but needed a coalition with the Irish Parliamentary Party to form a government. The price of the bargain was Home Rule.

The bill was passed, with the new Government of Ireland Act coming into effect in 1914. Ireland would have its parliament.

The Ulster Unionist Party had been created in 1905 for the express purpose of resisting Home Rule. The chief architect of that resistance was James Craig, the MP for the Irish constituency of East Down. He knew the moment called for a charismatic leader and he found the perfect candidate in Edward Carson, a barrister and pro-union politician from Dublin.

All means necessary

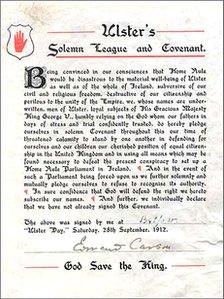

Each person who signed the Covenant received a personal copy, this is Edward Carson's version.

Craig's master stroke was the Ulster Covenant, an oath that every man in Ulster would be called upon to sign. It stated that their right to remain citizens of the United Kingdom would be defended by "all means which may be found necessary".

Carson was an electrifying public speaker and galvanised support for the signing at huge rallies across the province. He was the first to sign the Covenant on 'Ulster Day', 28 September 1912, followed by Craig. In all, 237,368 Ulstermen followed suit, with nearly as many women signing a declaration to support them. Each was given a copy of their oath to carry with them at all times.

The Covenant itself was never presented to the government. In fact, it was never presented to anyone. It was simply a huge statement of defiance and intent, but one that the British government seemed confident it could ignore.

'Mutiny' and gun-running

Craig and Carson knew they must give the Covenant teeth. They discussed plans for a provisional government and commissioned a wealthy Belfast businessman and sometime adventurer called Major Frederick Crawford to arm the newly-formed, 100,000 strong militia of the Ulster Volunteers.

By March 1914, the situation was worrying enough for the government to instruct the British Army to move reinforcements into Ulster. Army officers at Curragh, the principal barracks in Ireland, resigned en masse rather than play a part in enforcing Home Rule. Newspapers breathlessly described a 'mutiny' and the government rapidly backed down. The officers were all reinstated.

Unionists saw this is a significant victory and it was quickly followed by another. Major Crawford's gun running proved highly successful. In April 1914, he smuggled in a colossal haul of 25,000 rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition from Germany, landing them at Larne, County Antrim.

Ulster Volunteers unpack their guns smuggled from Germany

The nationalist militia of the Irish Volunteers responded by landing a thousand German rifles in broad daylight at Howth in Dublin Bay, the Kaiser apparently being only too willing to facilitate armed conflict within the United Kingdom.

The bigger crisis

With the situation rapidly sliding towards violent confrontation, King George V intervened to bring the parties together at Buckingham Palace for an emergency conference in July 1914. The talks ended in deadlock and civil war became a very real prospect.

But within two weeks, the crisis in Ireland was entirely defused by a crisis of much greater proportions. Germany had invaded Belgium and the United Kingdom plunged into four years of global conflict.

Men of the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Irish Volunteers put aside their differences and rallied to the defence of the Empire, fighting and dying in their thousands in the ranks of the British Army.

The Government of Ireland Act was shelved until after the war, but it was already clear from the strength of unionist opposition and the Curragh Incident that the British Government could not make Home Rule a reality on the ground.

An amended act became law in 1921. It effectively created two 'Home Rule' states by partitioning Ireland into the six counties of Protestant majority in the north east - Northern Ireland - and the rest of Ireland - Southern Ireland.

It was envisaged that both would remain within the union, but an attempt in 1918 to extend conscription to Ireland proved the final nail in the coffin.

In the south of Ireland, the call for Home Rule had given way to a more militant push for independence, led by the separatist Sinn Féin party. A guerrilla war erupted against British rule and in 1922 the Irish Free State was created.

Nothing to fear

In Northern Ireland, Carson was revered by unionists as their saviour. But he personally saw partition as a failure and resigned as leader of the Ulster Unionists in 1921.

In a speech that year he warned: "We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority. Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority."

The true architect of the Ulster Covenant and the founding father of the state of Northern Ireland was James Craig. He went on to become Northern Ireland's first prime minister and to a future shaped by his colleague's prophetic words.