'Signed in blood' claim challenged by scientific test

- Published

One of the legends of the Ulster Covenant, which celebrates its 100th anniversary on 28 September 2012, is that Major Frederick H Crawford signed it in his own blood.

Many sources quote this as an unchallenged fact, but a scientific test carried out on the signature by Dr Alastair Ruffell, of Queen's University Belfast, has found no evidence to support the claim.

"I'm 90% sure this isn't blood, but there is that margin of error, as this material has been uncontrolled for 100 years," said Dr Ruffell.

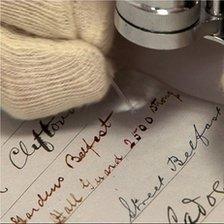

A small quantity of a substance called Luminol was injected into the signature. It is commonly used in forensic examinations and works by reacting with the iron in the blood's haemoglobin to produce a blue-white glow.

Major Crawford believed God had chosen him to help save Ulster

It is incredibly sensitive and can detect the tiniest traces, even in very old samples.

"Some years ago we did a test in the Colorado desert where they put some blood on some rocks and we went back ten years later and we were able to find the blood using the Luminol test," said Dr Ruffell.

Major Crawford is revered as a hero by many of Northern Ireland's unionists for the pivotal role he played in the story of the Ulster Covenant.

He believed that God had chosen him personally to help save Ulster, which makes the probability that the blood is fake all the more surprising.

It is one of the stranger quirks of history that in 1912 the people of Ulster, then the northernmost province of Ireland, made it clear that they were prepared to fight the British to stay British.

The Ulster Covenant was an oath signed by nearly a quarter of a million men to maintain the union between Ireland and Great Britain "by all means which may be found necessary".

Guns and ammunition smuggled into Ulster by Major Crawford very nearly turned that oath into a civil war.

They prevented the British government from enforcing 'Home Rule', a devolved parliament for Ireland in which the Protestants of the north would have been greatly outnumbered by the Catholics in the south.

"He was a man of very forceful, strong ideas, very much a mover and shaker," said Ian Montgomery, archivist at the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, external.

Crawford was a pious and god-fearing man whose loyalty to the union bordered on fanatical. He also had an extraordinary knowledge of guns. In 1910, the architects of the Covenant, James Craig and Edward Carson, commissioned him to smuggle enough weapons into Ireland to arm the newly formed, 100,000-strong Ulster Volunteers militia.

Crawford's gunrunning was hugely successful. He secured more than 25,000 rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition from a dealer in Germany and landed them at Larne, County Antrim, by means of a daring plan that involved switching ships mid-ocean and sending a diversionary vessel into Belfast harbour.

He also organised the marshals on 'Ulster Day', 28 September 1912, when thousands of unionists descended on City Hall in Belfast to sign the Covenant. His signature bears testament to his role with the note "U.C. City Hall Guard 2,500" - a reference to the number of men under his command.

But, crucially, there were no witnesses to Crawford's 'blood signature'. The legend began with the man himself, in a handwritten note on his personal copy of the Covenant oath that reads: "I signed at 3:45 in City Hall in my own blood".

A small quantity of a substance called Luminol was injected into the signature

It would have been entirely in keeping with Crawford's beliefs to symbolically spill his blood for Ulster, which is perhaps the reason his claim has remained unchallenged for a century.

Unionist MLA Robin Swann is unconvinced by the results of the test.

"I'm confident enough that the 10% is enough for me to say that Fred Crawford signed the Ulster Covenant in his blood," he said.

Even today, 100 years later, his signature retains a rich red colour that might reasonably be expected to have darkened or discoloured over time if it were truly blood. Blood also makes bad ink because it coagulates and becomes unusable very quickly.

It could be that Crawford was mindful of these practicalities and felt the symbolic power of the gesture would not be lost if a better substitute could be found. Tantalisingly, he was well connected in the linen trade and would have had ready access to dyes.

The fountain pen with which Crawford signed still resides in the Ulster Museum, external. It may be that the definitive answer to the mystery of what exactly he used to sign the Covenant lies within its ancient reservoir.