On the frontier: Border Protestants give views on Irish unity

- Published

Talk of a vote to remove the Irish border and reunite the island has heightened recently

His bloodline can be traced back to one of America's folk heroes, and now Northern Ireland's own Davy Crockett is at the centre of a frontier struggle.

His farm on the outskirts of the city of Londonderry spans the Irish border, with County Donegal on the other side.

Like his famous ancestor, he is facing a battle on two fronts - first Brexit, now an Irish border poll.

"I would rather the border disappear and we were governed by London, not Dublin," he said.

"I value the NHS and all the facilities Northern Ireland has.

Davy Crockett is unconvinced that a united Ireland would benefit his farming business

"People have always moved from the Republic into the north, and not as much from the north into the Republic - what does that tell you?

"As a farmer and a businessman, it makes sense to stay in the UK, and I would imagine there are a lot of nationalists out there who share that view."

The prospect of a border poll was put back on the agenda north and south this week after the decision by Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to push for another independence referendum in her region.

Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil have been setting out their paths to a united Ireland.

That has prompted unionists to seek assurances from Prime Minister Theresa May that a border poll is not in her plans.

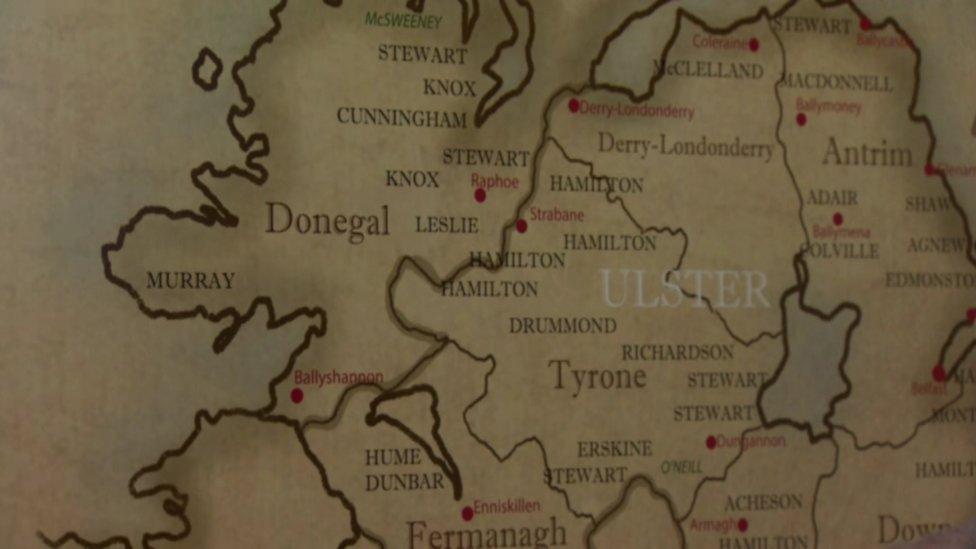

Views on Irish unity are mixed among border-based Protestants

But Protestants living along the border in Donegal have said they have mixed views on what unionists have to fear in a united Ireland.

Stewart McClean, from Newtoncunningham, describes himself as a "relic of the empire" - a unionist living in the Republic of Ireland.

He is in the process of rebuilding an Orange hall that was badly damaged in an arson attack two years ago.

"It was very unsettling and hard to understand why it happened, and to date we don't know why - nobody has ever been found for the attack," he said.

"We were very open in what we had - a few months earlier we had a group of ex-republican and loyalist prisoners here as part of peace and reconciliation projects.

An Orange hall in Newtoncunningham was gutted in an arson attack in 2015

"One of them, in his late 60s, said he had never been in an Orange hall before.

"So we thought we were being part of the greater good for the whole of Ireland, and then we get targeted for no apparent reason."

He said there was still "mistrust in the community in the Republic when it came to the Orange Order".

"It is not a cold place for the general Protestant community, but definitely in the case of the Orange there is a lack of understanding.

"That is why we plan to put in some kind of interpretive centre, so people can come in and understand what the Orange institution when the hall is rebuilt."

The Irish border is "never mentioned" in Donegal, according to Rev David Latimer

The experience is different for those who run the Ulster Scots heritage centre a short distance away at Monreagh.

"I would have to say any talk of the border on the northern side injects my co-religionists with fear, so therefore I think we have to be careful," explained Rev David Latimer, a director at the centre.

"In contrast, you come over here to east Donegal and the border is never mentioned.

"The people I minister here in Monreagh are happy - even though they are Protestant they are happy to identify as Irish citizens, interacting and mixing easily with their neighbours, who are Catholic.

"It's not a big issue over here."

As an Irish Protestant, Ian McCracken has faced questions about his identity

Retired teacher Ian McCracken, from St Johnston, has carried out researched into the views of Protestants along the border.

"Protestants in the Republic have been in a minority since 1922 and in a diminishing minority, something like 10% in 1922," he said.

"It's now roughly 4% of Protestants in the Republic, so I don't think Protestants in the Republic fear anything about a united Ireland.

He said he has never experienced discrimination, but he has faced questions about his identity.

"It's when you are asked are you Irish or are you British that people begin to think about it and feel challenged, and then it becomes an issue.

"I consider myself Irish, I have lived here all my life and wouldn't have lived anywhere else - I am quite happy to be identified as Irish."