Q&A: A guide to the DUP-Tory deal one year on

- Published

- comments

DUP-Tory deal - one year on

Tuesday marks a year to the day since Theresa May's Conservatives sealed a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in order to keep the government afloat.

It's known as a confidence-and-supply arrangement - meaning the government agreed a financial package with the DUP in exchange for support on certain issues.

Here's a guide to everything that happened in the lead-up to the agreement, what was included in the deal and how it has been working for the past 12 months.

Why was it agreed?

After Mrs May called the snap general election last June, she did not do as well as she'd hoped and ended up without a Commons majority.

The Conservatives got 318 seats, four short of the number a prime minister needs (technically it should be 326 seats - half of the overall number of MPs - but Sinn Féin's policy of abstentionism means its MPs do not take their seats).

That spelled bad news for Mrs May, as it meant her government could be defeated on crucial Brexit votes during the UK-EU negotiations. In order to get around that, she looked to the DUP and its 10 MPs, to help give her a working majority of 328.

What did it say?

At just three pages long, external, the deal sets out what the DUP agreed to support the Conservatives on, in exchange for financial support for Northern Ireland.

It also states that the two parties would set up a coordination committee to oversee how the agreement would work in practice.

It took two weeks of negotiations before the DUP reached a package of measures with the Conservative Party

The deal contains an assurance from the Conservatives that they will "never be neutral in expressing their support for the union".

It also includes a commitment from the government to uphold the Good Friday, or Belfast Agreement (the 1998 deal that brought 30 years of conflict in Northern Ireland to an end) and a clause that the deal will remain in place for the length of this Parliament (usually five years).

There is also a commitment that it will be reviewed by both parties at the end of each parliamentary session.

Why does the DUP not have ministerial positions?

Because it is not in coalition with the Conservatives. Rather, the two sides negotiated the confidence and supply arrangement. In exchange for support on key votes on Brexit, security and budgets, the DUP got money for Northern Ireland as well as the ear of the prime minister.

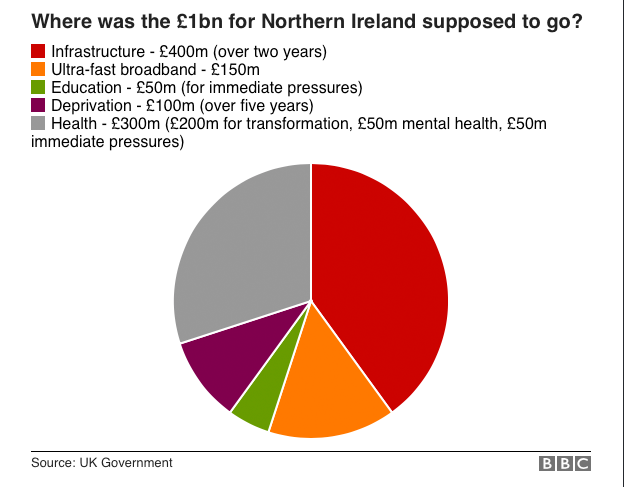

The party negotiated an extra £1bn in spending for Northern Ireland over 2018 and 2019. The deal, however, specified that the DUP is not tied-in to supporting the government on every matter.

Where was the £1bn for Northern Ireland supposed to go?

How much money been spent so far?

In the months following, there was concern that the money would only be able to be spent when Stormont was restored.

But in March, the government announced that £410m of the £1bn deal would be included in a new Stormont budget with money dished out to various areas.

Downing Street has said that so far £430m has been released. In 2017/18, £20m was given to health and education while the £410m allocated for the Stormont budget is currently going through parliamentary approval procedures.

Money for health was recently allocated to improve emergency department services in County Down.

In April, the government said a consultation would take place to see how the £150m for broadband could best be used. It is understood that it could be 2020 before that investment materialises.

What else did the DUP secure?

Viewed as shrewd negotiators from decades of talks in the Northern Ireland peace process, the DUP also gained guarantees from the Conservatives on a range of policy priorities - such as keeping the guarantee to increase state pensions by at least 2.5% a year, to maintain defence spending, and agriculture spending in Northern Ireland at the same level for the rest of the current parliament (which theoretically takes us to June 2022).

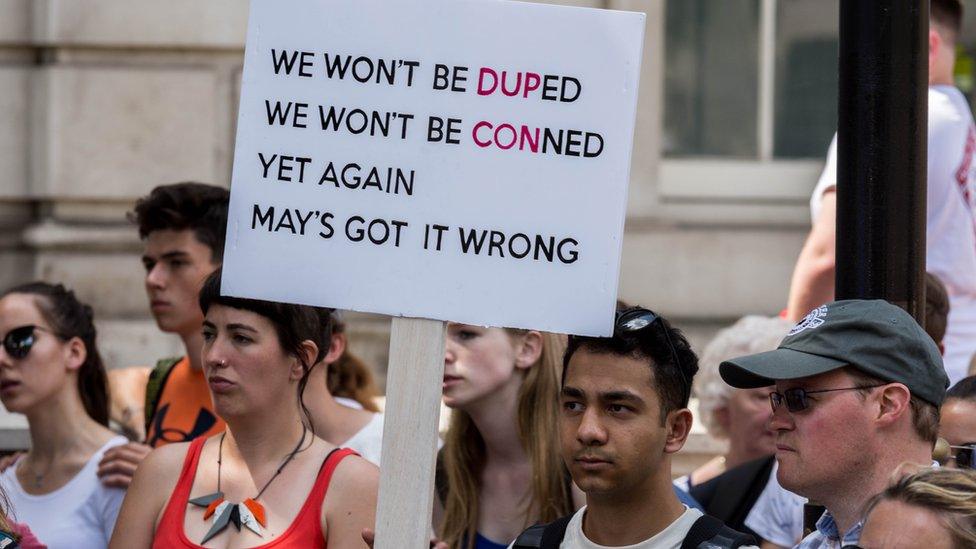

People were unhappy with the deal because of the DUP's stance on some social issues

Was everyone happy about the deal?

Not exactly. The DUP's deep religious roots mean it staunchly opposes abortion and same-sex marriage.

When the deal was announced, there was criticism of Mrs May from some of her own MPs who did not want their party to be associated with the DUP's views.

South Cambridgeshire MP Heidi Allen told the Commons she could "barely contain her anger" at the agreement.

The former Conservative Party chair Lord Patten even described the deal as "toxic". Scotland and Wales also expressed concerns that Northern Ireland could get special treatment from the government.

Has it affected politics in Northern Ireland?

When the deal was reached, power-sharing in Northern Ireland had stalled. The DUP-Sinn Féin executive had collapsed six months earlier, after a scandal concerning a flawed green energy scheme.

Several rounds of talks chaired by the British government had failed - and when the DUP-Tory deal was announced some argued it had set the process back even further, making it harder for the British government to play its traditional role of neutral mediator.

A year on, there's been no restoration of Stormont or implementation of direct rule from Westminster, leaving Northern Ireland in limbo.

The government says it is still committed to getting devolution up and running again, but has been criticised by other Stormont parties for being too close to the DUP.

Several rounds of talks between the DUP and Sinn Féin have collapsed. The latest attempt failed in February

What about Brexit?

While the DUP has stood by its promise to back the government on Brexit votes in the Commons, things were not so rosy last December.

Just six months into the arrangement, the DUP threatened mutiny after criticising a proposal between the UK and the EU about the future of the Irish border.

The DUP said its red line was any situation where Northern Ireland was treated differently from the rest of the UK. It forced the government to retreat from that plan, and to date, there has not been enough progress on the border question to allow the UK and EU to settle on a way forward.

This issue could cause more rifts between the DUP and the Conservatives for some time to come.

How much longer will the deal last?

That depends on who you ask.

Technically, it could last as long as the two parties agree to keep the agreement in place. Potentially up until the next general election is called.

But coalitions and minority governments, no matter the form they take, are not often thought of as stable settings for governance - particularly in this period with uncertainty around Brexit and the stalemate at Stormont. The DUP's deputy leader Nigel Dodds has insisted that it is "not a temporary two-year deal", but Mrs May might not be just as confident.

- Published27 June 2017

- Published26 June 2017

- Published26 June 2017

- Published26 June 2017

- Published26 June 2017

- Published12 June 2017