Profile: Arthur Scargill

- Published

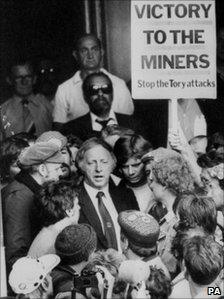

Mr Scargill defined the industrial turmoil that dominated the 1980s

The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) has stripped ex-president Arthur Scargill of his voting rights - threatening to end the career of one of the most divisive figures in Britain's recent past.

His year-long stand-off with Margaret Thatcher in the 1984 miners' strike was one of the defining events of the era.

For Mr Scargill, a Marxist dedicated to the overthrow of Mrs Thatcher's Conservative government and capitalism in general, it was the fight he had been building up to all of his life.

TV images of him in his trademark baseball cap with megaphone in hand, or being arrested amid violent skirmishes, came to define that dispute and the industrial turmoil that dominated the 1980s.

Mr Scargill, who had obtained a "hit list" of mines that the government was planning to close, was fighting for the very survival of his industry and the communities it sustained.

Pit closures

But his decision not to hold a national ballot led to bitter divisions among the miners he led, and the wider Labour movement.

After the failure of the strike, the NUM split and the Union of Democratic Mineworkers was created - largely as a result of Mr Scargill's actions.

It was little comfort to NUM members that the pit closures he had predicted came to pass, and more than 100,000 miners lost their jobs - decimating the once mighty union in the process.

The NUM had 250,000 members when Mr Scargill was elected president in 1982. Prime ministers may once have trembled at the mention of its name, but it is now a tiny organisation, with about 3,000 members.

Arthur Scargill was a working class hero to some miners in 1984

Mr Scargill, 72, first came to prominence in the early 1970s, when he was involved in a mass picket at the Saltley Gate coking plant in Birmingham.

He was a new type of union leader for a more bitter and divided era in industrial relations.

There were no cosy chats at Number 10 over beer and sandwiches under his leadership. Compromise was not in his vocabulary.

His aggressive, finger-pointing style of speech-making as he climbed on to the roof of a concrete toilet block to rally the "flying pickets" at Saltley would become an increasingly familiar image as the decade unfolded.

Emboldened by the NUM's humbling of Edward Heath's government in the 1974 miners' strike, he ensconced himself in the Yorkshire NUM's Barnsley headquarters as the area's leader, setting his sights on the national leadership.

He eventually replaced the wily, pragmatic Joe Gormley as NUM leader, in 1981.

He was elevated to the status of working class hero by some miners during the 1984 dispute. Others blame him for turning an industrial dispute into what seemed at times like a personal showdown with Mrs Thatcher.

Corruption claims

But trade unionism for Mr Scargill was never just about improving pay and conditions for workers, and saving jobs, it was part of a wider struggle against the forces of international capital.

After the 1984 strike, Mr Scargill was elected lifetime president of the NUM. He received an overwhelming majority of the votes but it was a controversial election with some candidates complaining they were not given enough time to prepare.

There was further controversy in 1990 when the Daily Mirror made what turned out to be untrue allegations of corruption against him. The case against Mr Scargill and other union officials collapsed in court.

He stepped down from leadership of the NUM at the end of July 2002, to become its Honorary President. He was succeeded by Ian Lavery, who became a Labour MP at this year's general election.

Since standing down from union activities, Mr Scargill has fought a series of elections - largely without success - with his Socialist Labour Party, which advocates widespread nationalisation of industry and withdrawal from the EU.

In the 2001 general election, he stood against Peter Mandelson in Hartlepool, winning just 2.4% of the vote.

He now faces the far greater humiliation of being expelled from the union to which he has dedicated his life.

- Published25 August 2010