The Ed Miliband Story

- Published

He may have served in Gordon Brown's cabinet, but few people outside politics had heard of Ed Miliband before he was elected leader of the Labour Party in 2010, a post he has now relinquished in the wake of Labour's election defeat.

He had spent much of the first 40 years of his life in the shadow of his older brother David, the former foreign secretary.

He did the same course - Philosophy, Politics and Economics - at Oxford University, at the same college, and followed David into a similar backroom role in the Labour Party, albeit on different sides of the Tony Blair/Gordon Brown divide. The two even lived in neighbouring flats in the same building for a while.

They both sat in Gordon Brown's cabinet, with Ed filling the less high profile role of climate change and energy secretary.

Ed used to introduce himself at meetings as "the other Miliband".

His stunning victory in the 2010 leadership contest caused a rift in the Miliband family that is still healing.

David Miliband (R) left UK politics after losing the Labour leadership battle to his brother

Mr Miliband himself has admitted it has been more difficult than he expected.

David was offered a shadow cabinet role but opted to leave British politics altogether, taking up a job as the head of the International Rescue charity in New York, avoiding speculation about rivalry with his younger brother that would surely have followed had he stayed around.

Ed Miliband: ''It is time for someone else to take forward the leadership of this party''

So who is Edward Samuel Miliband?

His supporters insisted during the leadership campaign that he was more "human", less aloof than David.

He is a self-confessed maths "geek" who was a secret Dallas fan as a boy - they are hardly Bobby and JR, but Ed had enough of a ruthless streak to challenge his brother for the job long thought to be his.

Marxist father was fierce Labour critic

Ed Miliband was close to his lecturer father, Ralph

Mr Miliband has made much of the fact he went to an ordinary North London comprehensive school.

And while this is true, his childhood will probably have been a little more colourful, and certainly more intellectually stimulating, than that of the average North London schoolboy.

His father, Ralph, a Polish Jew who fled the Nazi invasion of Belgium in 1940, was one of the leading Marxist theorists of his generation - and a fierce critic of the Labour Party. Their mother, Marion Kozak, is also a well-known figure on the British left.

Fast facts: Ed Miliband

Ed Miliband lives in North London with barrister wife Justine Thornton and their sons Daniel and Samuel

Age: 45

Electoral history: MP for Doncaster North since 2005. This is his first general election as Labour leader

Family: Lives with wife, Justine, and two young sons in north London

Background: North London Comprehensive school, Oxford University, Treasury

Leisure: Boston Red Sox fan, named A-Ha's Take On Me as one of his Desert Island Discs and displayed skills with a pool cue during election campaign in a game with Ronnie O'Sullivan

Growing up, their Primrose Hill home played host to the leading intellectuals and Labour politicians of the age, with dinner guests including Ken Livingstone and Tariq Ali.

The family's basement dining room was the scene of high-minded and often heated debates between major figures on the Left.

Mr Miliband has faced ridicule in the press

The Miliband brothers were always encouraged to chip into the debate with their own opinions and, apparently, Tony Benn was even known to have given the brothers a few pointers with their homework.

"[They were] very, very fresh lively, intelligent… and I must admit Ed amazed me by being able to do the Rubik's Cube... in one minute 20 seconds and, as I recall, just with one hand too," remembers socialist academic Robin Blackburn, a close friend of Ralph's.

Ed has spoken of how he bonded with his father when he accompanied him on trips to the US, where Ralph worked as a lecturer. It is also where he became a fan of the Boston Red Sox baseball team.

Leadership rivalry 'was huge strain for mother'

But although he is sometimes said to be politically closer to Ralph than his brother, in truth the two Miliband brothers are worlds away from his brand of socialism.

Although no lover of Soviet-style one-party rule or violent revolution, he had abandoned the Labour Party long before his sons were born, believing socialism could never be achieved through Parliamentary means.

Ralph died in 1994, a few weeks before Tony Blair became Labour leader, but had viewed with unease his sons' part in creating what would become known as New Labour.

Their mother Marion, an early CND activist and human rights campaigner, who is a leading member of the Jews for Justice for Palestinians group, and who, unlike Ralph, remained in the Labour Party, is thought to have been a greater influence on their political development.

"There's no doubt that Ed got a lot of his drive from Marion and a lot of his feel for nitty-gritty grassroots politics from Marion too," says Dr Marc Stears, politics fellow at the University of Oxford.

Friends say the leadership contest between the brothers was a huge "strain" for Marion. She has even told people it would have been much easier had they simply become academics rather than politicians.

David and Ed's background helped speed their way into Labour politics - Ed spent the summer after his O-levels doing work experience for Tony Benn, then a senior Labour left-winger. Mr Benn would reward him years later by backing his leadership campaign.

By their teenage years, both brothers were fully fledged campaigners for Labour. Ed was never part of the "cool" set at school, although he has joked that he did not get beaten up too often.

Number crunching skills attracted Brown's attention

Ed Miliband came to be seen as one of Gordon Brown's key backroom allies

Ed has spoken about how the experience of seeing equally bright pupils, from less privileged backgrounds, failing to reach their potential had a profound impact on his politics and outlook.

The more academically gifted of the two, Ed did better than David in his A-levels, following his brother to Corpus Christi College in Oxford, where he became involved in student activism.

"My best four weeks at university were when we had a rent dispute with the college," he told The Guardian in an interview, external.

"I wasn't particularly bookish; what really got me going was student activism, and mobilising people. It was quite a hard thing to recognise if you come from an academic family, but, if I'm honest, it's true. Politics always motivated me more than academia."

At the time, he was described as being less opinionated than his brother, who had a reputation as fiercely bright but rather socially inept.

After briefly working as a television journalist, Ed was taken on by current deputy Labour leader Harriet Harman, then a shadow minister, as a speech writer and researcher.

His number-crunching skills soon brought him to the attention of the then shadow chancellor.

Gordon Brown "burgled him off Harriet", Charlie Whelan, Mr Brown's former spin doctor, has said.

Diplomatic skills 'used to make peace with Blair's No 10'

When Labour came to power, Ed was pitched into the never-ending turf wars between the Treasury and Downing Street, coming to be seen as one of Mr Brown's key backroom allies.

He gained a reputation as something of a diplomat, whose skill at defusing rows was reportedly much in demand in the escalating battle between Brownites and Blairites.

It is said that Ed would often be despatched from the Brown camp to make peace with Downing Street, where David worked as head of Blair's policy unit.

"I was the one who tried to bridge some of the nonsense that there was," is how he now describes his role.

But he baulks at the usual description of himself as a "Brownite", claiming to be one of the least "tribal" of MPs.

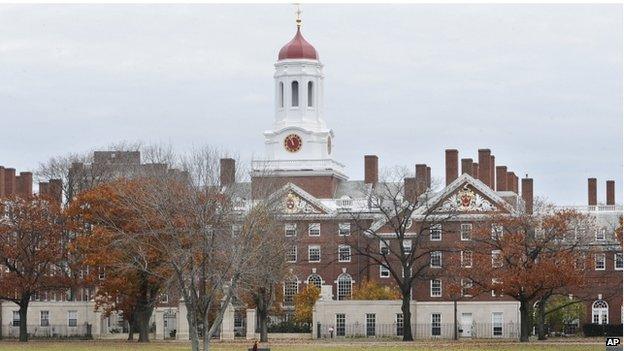

In 2003, he spent a year's sabbatical at Harvard University, to study and lecture at Harvard's Centre for European Studies, before becoming an MP for the safe seat of Doncaster North in 2005.

He lives in a fashionable North London district close to where he grew up, with barrister wife Justine Thornton and their two young sons Daniel and Samuel.

Mr Miliband spent a year studying and lecturing at Harvard University

Ridiculed for his voice and appearance

The couple, who had lived together for several years, got married in May 2011.

Support from the trade unions proved decisive in Ed Miliband's Labour leadership victory, and he has sought to move the party on from the New Labour era, projecting a more left wing message on tax and inequality.

He has also distanced himself from the Iraq War, calling the 2003 invasion a "tragic error" and saying he would have voted to give weapons inspectors more time had he been an MP at the time.

His relationship with the New Labour establishment - most of whom backed David for the leadership - has been prickly at times, although Tony Blair buried the hatchet by giving a supportive speech during the general election campaign.

But although the party has avoided the psychodramas and splits some had predicted after his election, Mr Miliband has had a far from easy ride as Labour leader.

He was ridiculed from the beginning by the media for his voice and appearance, with cartoonists portraying him as Wallace, from the Wallace and Gromit animations.

The mockery reached its zenith with a photograph of Mr Miliband struggling to eat a bacon sandwich.

Cartoonists portrayed Mr Miliband as Wallace, from the Wallace and Gromit animations

'I am not from central casting'

But there was also internal Labour criticism that he lacked the leadership skills to take the party back into power and that his focus on issues such as zero-hours contracts and taxing the rich was too narrow. He was not reaching out to the middle-income, southern England voters Tony Blair had gathered up to win three general elections.

There were some unforced errors, such as forgetting to mention the deficit in his 2014 party conference speech and having to apologise for a grinning snap of him promoting the Sun newspaper.

But he has endured the most sustained campaign of press criticism levelled at a Labour leader since the days of Neil Kinnock.

Mr Miliband has made much of the way that he has stood up to vested interests - starting with Rupert Murdoch, over phone hacking, and then the energy companies, when he announced a planned price freeze.

But his personal poll ratings have been among the lowest of any Labour leader, well below that of the party itself.

He sought to do the only thing he could to counter the barrage of criticism about his style - attempt to make a virtue of it.

"I am not from central casting," he said in a speech last year.

"You can find people who are more square-jawed, more chiselled, look less like Wallace.

"You could probably even find people who look better eating a bacon sandwich.

"If you want the politician from central casting, it's just not me, it's the other guy.

"And if you want a politician who thinks that a good photo is the most important thing, then don't vote for me.

"Because I don't. Here's the thing: I believe that people would quite like somebody to stand up and say there is more to politics than the photo-op."

A bruising interview with Jeremy Paxman during the 2015 campaign saw Mr Miliband coin a catchphrase, of sorts

His Conservative opponents sought to make Mr Miliband's character an issue at the general election, constantly saying he was too weak and "in the pocket" of the SNP to be prime minister.

But the Labour leader had a better campaign than many expected, and saw a boost in his personal ratings, from an admittedly low base.

There were some mis-steps - his unveiling of a stone with six pledges carved in attracted mockery, even from sympathetic newspapers.

But he showed a new level of self-confidence to go with the resilience he had always possessed, even managing to coin a catchphrase of sorts in a bruising Channel 4 interview with Jeremy Paxman.

Asked if he was tough enough to stand up to Russian President Vladimir Putin, he replied, in a John Wayne style: "Hell, yes, I'm tough enough."

He even became something of a sex symbol, with a Twitter-based #Milifandom campaign.

But when the scale of Labour's election defeat became clear on the morning of 8 May, Mr Miliband resigned as party leader, saying he took "absolute and total responsibility" for the party's defeat.