Irish Republic bail-out in UK interest - George Osborne

- Published

Ireland bail-out: George Osborne says "we are seeking to help our friend."

Chancellor George Osborne has told MPs it is in the UK interest to join a rescue package for the Irish economy - including a direct bilateral loan.

He said Ireland was a "friend in need", a major trading partner with a banking sector closely linked to the UK's.

Although earlier reports put the loan amount at £7bn, the chancellor said talks were still continuing, although the figure was "in the billions".

Shadow chancellor Alan Johnson said he supported assistance "in principle".

But he told BBC Radio 4's PM programme that Britain was already contributing through the IMF and an EU mechanism, adding: "Why are we also entering into a bilateral agreement? That money seems to be extra."

Irish PM Brian Cowen has accepted up to 90bn euros (£77bn; $124bn) in loans from the European Union.

But the taoiseach has resisted calls to stand down, and, on Monday said his government would focus on preparing an austerity budget.

He said he would not dissolve parliament until after his emergency measures had been approved by parliament in the New Year.

He speech came after police intervened when about 50 protesters forced their way into a security hut at Government Buildings in Dublin.

'Situation unsustainable'

Earlier, Mr Osborne outlined some details of the "international financial assistance package" to MPs at Westminster - saying it would support a four-year plan for Ireland to cut its budget deficit to 3% of GDP. It would also support the reform of its banking sector.

He told MPs: "We are doing this because it is overwhelmingly in Britain's national interest that we have a stable Irish economy and banking system.

"The current Irish situation has become unsustainable. Their sovereign debt markets had effectively closed and had little prospect of reopening."

Asked earlier about reports the UK would contribute £7bn he said it was "around that, it's in the billions not the tens of billions". But he said details of the British, IMF and eurozone packages were still being worked out.

He told MPs: "This is a loan we can afford to make and will get back."

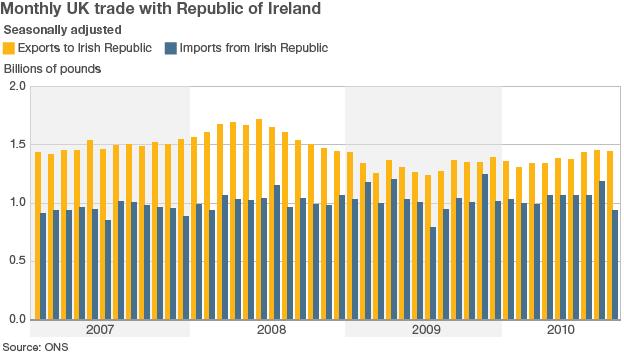

He said Ireland accounted for 5% of Britain's total exports - and two-fifths of Northern Ireland's exports. Two of the four largest High Street banks in Northern Ireland were Irish-owned, he added, and Irish banks also issued sterling.

Pressed on whether he would rule out offering any other eurozone countries bail-outs in future, he said it was not wise to speculate about other countries' finances but added: "I think there are very specific connections between the UK and Ireland which we don't have with other countries and that's why I think it's completely appropriate we make a bilateral loan in this case."

On the other parts of the rescue package, he said the IMF was "well resourced and able to meet the cost of the package for Ireland".

Mr Osborne said Britain would not participate in the eurozone stability fund of 440bn euros, but would take part in the 60bn-euro European financial stabilisation mechanism, which he said Britain was signed up to by the previous Labour government.

"The EU will lend money to Ireland on behalf of all 27 member states and the UK must accept its share of this contingent liability, which would arise in the unlikely scenario that Ireland should default on its obligations to the EU."

But there is some criticism of the proposals, which the BBC understands will require approval in a House of Commons vote.

Conservative backbencher Douglas Carswell told the BBC: "We shouldn't be paying to help keep Ireland in the euro. If we are going to pay to solve this crisis, we should be helping to pay Ireland to quit the euro .... At a time of austerity, again we are paying vast sums to the European Union."

Protesters have marched on the Irish parliament building in Dublin

Liberal Democrat MP Sir Alan Beith warned of public scepticism over the proposals. He said the public had been angry their money has been used to prop up UK banks and they would be angrier that it was being used to support foreign institutions.

Mr Osborne said he had been among those to oppose Britain's entry into the euro but added: "'I told you so' is not much of an economic policy. We've got to deal with the situation as we find it."

He said he was "not particularly happy" about being part of the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism but now was not the time to "try and pull ourselves out of that".

However he said he was working to make sure Britain "was not part of a permanent bail-out mechanism for the euro".

'Designed for disaster'

BBC business editor Robert Peston said the Royal Bank of Scotland had lent £53bn in Northern Ireland, which was insured by British taxpayers as RBS is a semi-nationalised bank, so if the Irish economy were to implode, that would generate big losses for RBS and the taxpayer.

He added that, assuming the money was paid back, the UK would be able to make a profit from lending money to the Irish Republic because it could borrow money at a lower interest rate than that it would charge Dublin.

Former Northern Ireland Secretary Lord Reid of Cardowan told the House of Lords that any constraints put on the loan should not restrict the country's growth, while fellow peer Lord Pearson of Rannoch, said the euro was "always designed for disaster".

EU Finance Commissioner Olli Rehn, speaking in Brussels, said the loans would be provided to the Irish Republic over a three-year period.