Concept of human rights being distorted, warns Cameron

- Published

David Cameron: The court "should not undermine its own reputation by going over national decisions where it doesn't need to"

David Cameron has warned that the concept of human rights was being "distorted" - and even "discredited" - by controversial decisions in Europe.

Speaking in Strasbourg, he said there was "credible democratic anxiety" about rulings on immigration and prisoner voting by the European Court.

The prime minister said he wanted decisions made at a national level to be "treated with respect".

Labour have accused the PM of "peddling myths" that "denigrate" the court.

The UK currently holds the rotating presidency of the Council of Europe, and in his speech to its Parliamentary Assembly on Wednesday afternoon, Mr Cameron promised to use the remaining months of its term to press for change.

Case backlog

The UK has clashed with the European court over a number of issues.

Last week, Strasbourg upheld a challenge by radical preacher Abu Qatada that deporting him from the UK to Jordan would breach his human rights.

Westminster is also embroiled in a row with the court over voting rights for prisoners. The UK's blanket ban on prisoners voting has been held incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights but last year MPs voted to keep it - although the vote was not binding. A new ruling is due on the case soon.

In his speech, Mr Cameron said no-one should "doubt the British commitment to defending human rights", but that did not mean "sticking with the status quo".

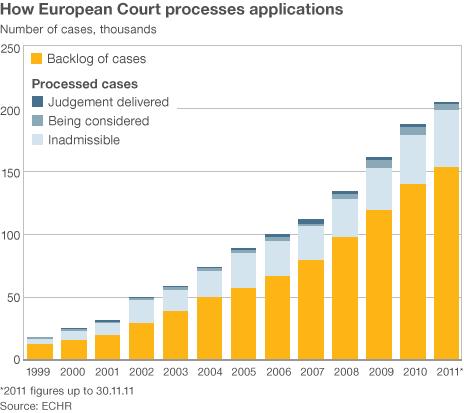

He argued there were three main problems facing the court - the first being the huge backlog of more than 150,000 cases.

Second, he said, was the fact that many of the waiting cases were trivial and were effectively turning the institution into "a small claims court".

He gave the example of an individual whose complaint was that his busy trip from Bucharest to Madrid "hadn't been as comfortable as advertised".

"In effect that gives an extra bite of the cherry to anyone who is dissatisfied with a domestic ruling, even where that judgement is reasonable, well-founded, and in line with the convention.

"Quite simply, the court has got to be able to fully protect itself against spurious cases when they have been dealt with at the national level."

The third problem, Mr Cameron said, was that the court is failing to take "enough account... of democratic decisions by national parliaments".

"Yes, some of this is misinterpretation - but some of it is credible democratic anxiety, as with the prisoner voting issue.

"I completely understand the court's belief that a national decision must be properly made, but in the end, I believe that where an issue like this has been subjected to proper, reasoned democratic debate and has also met with detailed scrutiny by national courts in line with the convention, the decision made at a national level should be treated with respect."

He said public concern around issues such as deportation mean that "the very concept of rights is in danger of slipping from something noble to something discredited - and that should be of deep concern to us all".

"And at the heart of this concern is not antipathy to human rights; it is anxiety that the concept of human rights is being distorted."

Slow process

Mr Cameron said he wanted to introduce new rules to improve the court's efficiency, its process for appointing judges and to "push responsibility to the national system".

"That way we can free up the court to concentrate on the worst, most flagrant human rights violations - and to challenge national courts when they clearly haven't followed the convention."

The BBC's deputy political editor James Landale said it was likely to be a slow process as the UK had to get the unanimous backing of the 47 member states. It only holds the Council of Europe presidency until May.

But Attorney General Dominic Grieve told the BBC he believed the chances of getting reform were "extremely good" because there was widespread backing for the UK's proposals.

Ahead of Mr Cameron's speech, the court's top judge, Sir Nicolas Bratza QC, said "the criticism relating to interference" in UK affairs was "simply not borne out by the facts".

"It is disappointing to hear senior British politicians lending their voices to criticisms more frequently heard in the popular press, often based on a misunderstanding of the court's role and history, and of the legal issues at stake," he wrote in the Independent newspaper., external

He said it was unfortunate that the prisoner voting issue "has been used as the springboard for a sustained attack on the court ".

'Restless backbenchers'

Shadow Justice Secretary Sadiq Khan said the prime minister seemed "more concerned with placating his restless backbenchers than he is about protecting and promoting human rights across Europe".

He said Mr Cameron was less concerned about "a positive debate" on updating the way the court worked and more interested in "the peddling of myths that denigrate the human rights successes of the court and the convention".

Labour peer and human rights lawyer Baroness Helena Kennedy QC said British cases making it as far as the court were few - and most cases came from countries with poor human rights records.

Nigel Farage, leader of the UK Independence Party which campaigns for the UK to withdraw from the European Union, accused Mr Cameron of "blustering to no avail about the harmful effect of the European Court of Human Rights".

"The stream of ridiculous judgements from the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, protecting drug dealers and known terrorists, will continue to bind us in knots while we are signed-up members of the EU."

But Donna Covey, chief executive of the Refugee Council, said the court had "protected the rights of many UK residents who have been let down by our justice system and it is important that this safeguard exists to hold our government to account when necessary".

The European Convention on Human Rights protections - such as the right to a private and family life and freedom of expression - became directly enforceable in UK courts in 2000 via the Human Rights Act.

In their 2010 election manifesto, the Conservatives pledged to replace the Human Rights Act with a UK Bill of Rights.

But when their entered government in coalition with the Lib Dems, who support the Act, they instead agreed to "establish a Commission to investigate the creation of a British Bill of Rights that incorporates and builds on all our obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights".

- Published25 January 2012

- Published19 November 2011

- Published27 October 2011

- Published8 September 2011