David Cameron plays for time on European human rights

- Published

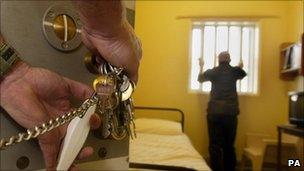

The ECHR has infuriated Mr Cameron by insisting Britain should allow prisoners to vote

Once upon a time a young Conservative MP hoping to win the leadership of his party floated the idea of Britain leaving the European Convention on Human Rights.

He said that if Britain wanted to be able to deport terror suspects, the government should amend the human rights laws "or, if necessary, leave - perhaps temporarily - the ECHR".

That was David Cameron in August 2005, appealing to Conservatives who might have been attracted to his rival, David Davis.

Seven years on, and within the constraints of government and coalition, the prime minister is on the same turf but now perhaps a touch more cautious than his younger self.

There will be no call from Mr Cameron in Strasbourg for Britain to withdraw from the ECHR. But he knows that that is just what some in his party desire.

This is the context of the PM's speech later.

Yes, he will call for reform of the European Court of Human Rights - more efficiency and less backlog; more national decision-making and less interference.

Moderate tone

But his tone will be moderate, designed to win allies here in France, not in Fleet Street.

For as the current holder of the six-monthly rotating presidency of the Council of Europe, the prime minister has at least a chance to make a difference.

There is an appetite for reform among some of the 47 member states.

For them, Mr Cameron's most persuasive argument is that without reform the court could undermine support for human rights.

The ECHR is a bugbear for many Tory MPs

But even if there is agreement in principle by May - when the Albanians take over the presidency - this reform is long-term stuff.

It could take years. In other words, the court would have lots of time to carry on ruling against the deportation of terror suspects like Abu Qatada, or giving the vote to prisoners.

So the question for the PM is this: will his reforms satisfy those voters and MPs who think the court interferes too much?

Will a court that focuses more on violations of fundamental rights challenge fewer decisions made by Britain's courts and parliament? By making the court better, will it interfere less?

Buying time

The truth is that a convincing argument for reform buys Mr Cameron time.

Tory MPs, still basking in the afterglow of the veto-that-was-not-quite-a-veto, are still ready to give their leader the benefit of the doubt.

There is little pressure for an early move to scrap the Human Rights Act and replace it with a British Bill of Rights.

But one day soon, the ECHR will rule again on the right of prisoners to vote.

There is an Italian case pending that could complete at any moment.

The expectation is that the court will reaffirm its previous judgement, namely that a blanket ban on prisoners voting is illegal.

And then David Cameron will have to decide whether Britain's laws are made in Westminster or Strasbourg.

And no amount of reforms to the ECHR will get him off that hook.

- Published25 January 2012

- Published12 April 2011