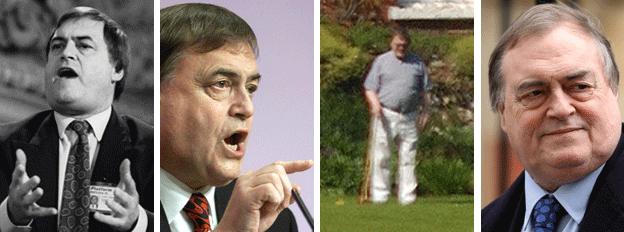

The John Prescott story

- Published

A political career spanning five decades has taken him from union shop steward to the peerage via high office - but Lord Prescott's ambition to be one of the first police and crime commissioners proved to be beyond his reach.

"Vote for me and I'll always put you and beating crime first," 74-year-old Lord Prescott had told voters in the Humberside Police force area.

He won an unlikely endorsement: "It would be a magnificent thing for British politics if he wins," wrote, external the Telegraph's Peter Oborne ahead of the poll.

Although his public profile far outshone any of his rival candidates', the electorate remained unconvinced and he was beaten by the Conservative candidate - something that will have been a bitter blow for a man who has dedicated his life to fighting "the Tories".

Even a helping hand on the campaign trail from his old boss, Tony Blair, who flew in to man the phones for a few hours, and was rewarded with a "Prescott for sheriff" badge, could not save him from defeat.

In a gracious speech, the former deputy PM offered his congratulations to victorious rival Matthew Grove - but no clue as to whether he would now be departing the electoral scene.

It is hard to imagine a man so in love with being on the campaign trail parking up his battle bus for good, but there are few realistic opportunities around to get it back on the road.

So now seems a good time to take a look back at his extraordinary career.

Lord Prescott was elevated to the peerage in 2010, despite reportedly having once said: "I don't want to be a member of the House of Lords. I will not accept it."

At the time, he defended the decision because it would give him continued influence over environmental policy.

But he has refused to treat the red benches as an upmarket retirement home, using them as a platform to carry on campaigning.

His most robust interventions in Lords debates have involved attacking, external the government's response to the phone-hacking scandal.

For Lord Prescott, the matter was personal: his lawyers alleged that the News of the World had placed him under surveillance, and in 2012 he won a pay-out from the paper's parent company, News International.

With more than 150,000 followers on Twitter, he has seized on new technology to wrest power back from the press, once apparently, external using the social media site to expose a "completely made up" quote purporting to be from him and obtaining swift redress.

At the height of his career, he was a favourite target of the tabloids, dubbed "Two Jags" - after the two official Jaguar cars he is meant to have had at one point.

But he was always fiercely proud of his working-class roots, portraying himself as firmly "Old Labour".

His down-to-earth image proved vital to the New Labour project, forming a bridge between the party's grassroots and the new breed of Labour politician at the top of the party.

"We are all middle class now," he said before the 1997 general election, neatly summing up Tony Blair's "big tent" philosophy.

He was rewarded shortly after Labour's landslide victory with his own, specially-created "super department", spanning transport, planning, the regions and the environment.

But he ended his time in government after 10 years with no ministerial brief of his own and was seen by many as a peripheral figure.

Croquet lover

He admitted an affair with former secretary Tracey Temple in 2006 and was subsequently relieved of many of his duties.

He kept his salary, an apartment at London's Admiralty House and other perks but felt compelled to give up his grace and favour country pile, Dorneywood, after being pictured on its lawns playing croquet with his staff.

Prescott taunted a crab called "Peter" when he stood in as PM Tony Blair

But there was still a sense that Mr Prescott provided an antidote to the spin and slick presentation of New Labour.

He was often ridiculed by Parliamentary sketch writers for mangling the English language. The modern management speak that infects politics seemed to give him particular problems.

But to supporters he appeared an ordinary man, facing the intellectual bullying of those who had a better education.

Mr Prescott's favourite film is Billy Elliot, which tells the tale of a northern working-class boy who fights prejudice and poverty to become a leading ballet dancer.

The parallels are not hard to see.

'Most typical family'

Prescott was born in Prestatyn, north Wales, in 1938, the son of a railwayman.

His childhood was neither affluent nor deprived. Indeed, the Prescott family won £1,000 in a competition to find the "most typical British family of 1951".

He failed the 11-plus - something which still grates even today - and attended Ellesmere Port Secondary Modern before joining the Merchant Navy, where he worked as a ship's steward during the last days of the great ocean liners.

Among those he served with drinks was a former prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden. And though the wages - including generous tips from passengers - were very good, it brought home to Prescott the reality of the class divide.

Mr Prescott, as he then was, honed by his time as a shop steward in the National Union of Seamen and a spell at Ruskin College in Oxford, soon made his mark on the national stage.

He entered Parliament in 1970, a Bennite class-warrior, joining Labour's shadow cabinet as a transport spokesman in 1979.

Perhaps his greatest claim to fame came in 1993 when he called for the end to the union block vote and was credited with saving the then Labour leader John Smith from a humiliating defeat.

But his lack of education, and taunts from the Conservative benches - including Nicholas Soames' "Mine's a gin and tonic, Giovanni, and would you ask my friend what he's having?" - left Prescott with a hatred of the Tories.

After Smith's death Mr Prescott's star rose further - deputy leader in 1994, deputy prime minister three years later.

His mantra was clear and unwavering - Labour had to show "traditional values in a modern setting".

Mr Prescott's role as a power-broker and counsellor smoothed the often strained relationship between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and also helped ensure a trouble-free transition from one leader to the other.

And his 2004 assertion, that "the tectonic plates appear to be moving" within the government, seemed to suggest he thought Tony Blair should have made way for his successor sooner rather than later.

His original title was deputy prime minister and first secretary of state for environment, transport and the regions - "the only minister with a job title bigger than his vocabulary", according to Sir Norman Fowler.

In his environment role - which was later hived off into a separate department - he was a key player in agreeing Kyoto Protocol on climate change in 1997.

But his dream of directly elected regional assemblies hit the rocks in 2004 when north-east England overwhelmingly rejected the idea in a referendum.

Verbal slip-ups

Mr Prescott's reputation for hot-headedness remains.

The man who said in 1994: "I don't pursue vendettas or punch people on the nose," lit-up the dull 2001 general election by, well, punching a man on the chin.

"John is John," shrugged Tony Blair the following day, after pictures of Mr Prescott scuffling with a bystander who threw an egg at him had been beamed around the world.

Then there is Mr Prescott's singular verbal style.

"The green belt is a Labour achievement, and we mean to build on it," he told one reporter. After a rough flight, Mr Prescott quipped: "It's great to be back on terra cotta."

And he once described government transport policy thus: "We are now taking proper, putting the amount of resources and investment to move what we call extreme conditions which must now regard as normal."

Tony Blair once told a Labour conference a story about the man employed by Prince Philip of Macedonia, the father of Alexander the Great, to carry a black stick with a pig's bladder on the end and wake him up at night to remind him he was only mortal.

"Would I need a bloke with a stick and a pig's bladder when I have John Prescott?," joked Mr Blair.

In his maiden Commons speech in 1970, Mr Prescott raised the economic plight of the port of Hull, urging the government to "rid the docks of the private employers and go on further, I hope, to take the docks into public ownership".

His pitch for votes in the PCC election suggested his political philosophy had changed little over the 42-year intervening period: "I passionately oppose... any attempt to privatise the police."

Despite the loss of one recent political scrap in Humberside, Lord Prescott's pugnacious nature is sure to reappear on both the ancient platform of the UK's upper chamber of Parliament, and the slightly less ancient platform of Twitter.