Child poverty: Take parental addiction into account, urges Duncan Smith

- Published

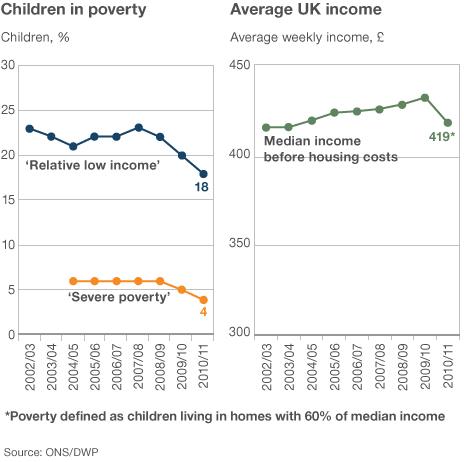

Families are currently considered to be in poverty if they are on less than 60% of the median income

Parental addiction and other factors should be taken into account when considering a new definition of child poverty, a cabinet minister is to say.

A "fixation" on relative family income as a benchmark has led to misleading outcomes, Iain Duncan Smith will argue.

Giving money to parents with drink and drug problems may lift families above an "arbitrary" poverty line but increase dependency, he will add.

Campaigners say ascribing child poverty to addiction is not factually accurate.

Child poverty is most commonly measured on the basis of relative income, with those living in households on less than 60% of median income regarded as being disadvantaged.

The median - the middle figure in a set of numbers - for 2010-2011 was £419 a week, down from £432 the year before.

'Chasing targets'

The government is reviewing how child poverty is classified and in a speech in London, the work and pensions secretary will call for a more "multidimensional" approach focused on changes in families' "life chances", not just income.

He will argue that figures indicating 300,000 children moved out of poverty last year should not be taken at face value as this was "largely due" to a fall in households' median income and those concerned were actually no better off than before.

This, he will argue, is symptomatic of a wider problem about the debate on child poverty which has been "fixated on a notion of relative income and moving people over an arbitrary poverty line at the expense of a meaningful understanding of the problem we are trying to solve".

"For too long government has chased income-based poverty targets without focusing on what happened to families they moved above the income line.

"I believe that we need to focus on life change so that families are able to sustain the improvement in their lives beyond government money."

'Cause of hardship'

While arguing income should remain a "key indicator" in definitions of poverty, Mr Duncan Smith will point to research conducted as part of a government consultation, external on the issue suggesting other factors are just as important.

He will highlight the issue of parental addiction to drugs or alcohol which, he will claim, "rarely features" in the poverty debate but which - for many people - is seen as an "obvious" detriment to a child's prospects.

Mr Duncan Smith will call for more "direct, intuitive thinking" about what factors hold children back and embed social and financial disadvantage.

"For a poor family where the parents are suffering from addiction, giving them an extra pound in benefits might officially move them over the poverty line," he will say.

"But increased income from welfare transfers will not address the reason they find themselves in difficulty in the first place.

"Worse still, if it does little more than feed the parents' addiction, it may leave the family more dependent not less resulting in poor social outcomes and still deeper entrenchment. What such a family needs is that we treat the cause of their hardship - drug addiction itself."

The last Labour government set itself a target of ending child poverty by 2020 but failed to meet its goal of halving the numbers by 2010-11.

According to official figures, 2.3 million children were below the poverty line at that stage - 600,000 more than Labour had wanted.

'Affording the basics'

But campaigners say real progress was made between 2000 and 2010 and have expressed concerns that this could be endangered by cuts to the welfare budget - including curbs on tax credits and housing benefit caps - central to the coalition's deficit reduction plan.

The Child Poverty Action Group said research conducted in 2008 had suggested less than 7% of those on benefits were problem drug users.

And the Children's Society accused Mr Duncan Smith of "stereotyping" families who were struggling to make ends meet.

"The vast majority of families in poverty are struggling because they can't afford the basics - not because they are wasting cash on drink and drugs," said its chief executive Matthew Reed.

"We know from our extensive work with families that parents are doing their very best.

"Every day they are making harsh choices between heating their home, buying school shoes or putting a hot meal on the table."

- Published14 June 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published29 May 2012