Political lives: David Alton on abortion, Militant and Clegg

- Published

Liberal leader David Steel (left) welcomes David Alton to the House of Commons in 1979

He's been assaulted, he's had his office attacked and he's angered North Korea. And as for Nick Clegg... well Lord Alton's never been one to hide his beliefs for an easy political life.

"Take an issue like gender-cide - how can anyone who says they believe in women's rights say it is legitimate, just as a matter of choice, to take away the right to life of an unborn girl?"

The young David Alton opposed abortion before he entered politics and it's an issue that has played a central role in his career since.

Just this month he has been demanding the government starts recording the gender of aborted foetuses to tackle the issue of sex-selective terminations.

His request was rejected, but Lord Alton is unlikely to be put off. This is a man who, in the 1980s, had his Merseyside constituency office burned out and his home picketed.

Lord Alton, as reasonable sounding and urbane as you'd expect from a House of Lords member - even on such an emotive issue - says he does "respect and understand why people hold diametrically opposed views to me - only a bigot or someone who's a complete fool wouldn't respect why people hold a contrary view".

He adds: "What saddens me is that there's a political correctness that tries to stifle debate about this issue. So anyone who dares say they think abortions are taking place too frequently, or too late, is immediately accused of being a misogynist or a bigot, or wholly against women's rights."

In the late 1980s he got a majority of MPs backing his bill seeking a cut from 28 weeks to 18 weeks in the legal limit for an abortion, but it lacked government support and was talked out. Subsequently there was a cut to 24 weeks, but he still hopes to see a cut to 14 weeks - "it's an issue that comes around again and again".

'Grimond go-ahead'

The 61-year-old would also like to see more effort to promote adoption "as an alternative where many more babies could be born instead of being aborted - especially where women feel they have no choice.

"That would be a more civilised way for dealing with these matters, but people are very often on tramlines, shouting abuse at each other rather than listening".

Among those who disagree with Lord Alton on abortion is one of his oldest political friends, Lord Steel, who was of course the young Liberal MP who piloted the change in the UK law in the 1960s to make abortion legal in the first place.

The young David Alton collected a petition at his school against the change - and took the precaution of writing to the then Liberal leader Joe Grimond to ask whether his anti-abortion views would make him unwelcome in the party.

"I got a reply saying it was entirely a matter of conscience - and that cleared the way for me."

And how. By the time he was 21, he was a councillor in Liverpool. At 23, he contested the two 1974 general elections. By 27, he was deputy leader of the council and housing chairman, and was an MP at 28.

David Alton arrives in Parliament

In his council role, he was amazed people twice his age wanted his advice, but says he learned quickly what the issues were - and is said to have done his bit to help end the slum clearance programme.

His time as a Liverpool councillor came just before Militant took control, but it was already a lively place to be - police had to be called one day when a man had his hands round Mr Alton's throat - "all of that experience gave me the courage to face some of the battles I had to face in the House of Commons".

During the 1980s he says he often agreed with the Trotskyist Militant's criticism of the Thatcher government but "I was diametrically opposed to the way they were going about things - turning your city into a battering ram, putting up barricades and taking illegal action was grossly irresponsible".

He thinks that the policies of the 1980s, the mass unemployment "putting people out of work and not providing anything else for them to do... created the benefits culture that we're having to deal with today".

Lord Alton puts some of the current government's economic policies on a par with the Thatcher government's. He has been outspoken recently on the threat to many disabled people that they might lose their Motability help as part of social security changes.

He says: "This devil-take-the-hindmost, this sharp-elbowed Britain, this beggar-your-neighbour Britain, this food-bank Britain is a place I feel very uneasy about.

"The comparisons with the 1980s couldn't be greater and I'm shocked to see Liberal Democrats in that coalition voting for welfare cuts and some of the changes to the National Health Service."

Mr Alton won five elections as a Liberal/Lib Dem candidate in first Edge Hill and then Mossley Hill in Liverpool - but stood down in 1997 having already left the Lib Dems on 1992 when the party decided to make abortion a party policy - it had previously been a conscience issue left to each member.

Alton 1992

Lord Alton calls this shift - together with the party's policy on euthanasia and experiments on human embryos - "liberal intolerance". The Conservatives still treat abortion as a conscience issue and, says Lord Alton, Labour has become more open on the issue.

His departure from the Lib Dems does not seem to have caused the then leader Paddy Ashdown any lost sleep - in the TV news report from that day, he says Mr Alton "has not played any part in building the party... for four or five years" and "his departure will be sad but won't make any difference".

Lord Alton is critical of his former party's decision to go into coalition.

"They were wrong. If they understood the old Liberal Party, they would know that in the 1920s and 1930s it led to the decimation of the Liberal Party - because in coalitions where you are such a small player you have no real control over events," he says.

"They should have allowed them [the Conservatives] to form a minority administration and said they would vote for every measure on its merits.

"But they were tantalised by the opportunity of becoming government ministers and clutching red boxes full of papers."

It doesn't sound as if he's a fan of current Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg.

"I don't know Nick Clegg, but he seems to have the reverse Midas touch," Lord Alton says.

In going for "big bang" reforms on voting and on the House of Lords, Mr Clegg "created so much hostility it cheated him of any chance of getting the proposals through, which didn't show much understanding of how the political process works", he adds.

'Casualties of strategy'

Instead, says Lord Alton, Mr Clegg could have insisted on changing the council elections system to the single transferrable vote as part of the coalition agreement, with the promise of a possible extension to Westminster elections.

On House of Lords reform, Lord Alton says Lord Steel's plans for incremental change were backed by many, but Mr Clegg "demanded so much he got nothing".

"On the keynote things he was after, he showed maladroitness. He is seen in the country as simply being a pawn in the hands of the larger party," he says.

And the result of that has been the party taking a hit in the polls and many councillors losing their seats, including in Liverpool.

"It just fills me with sadness - these are my friends and I'm sorry they have been casualties of strategy," Lord Alton says.

Mr Alton, who was the youngest MP when he surprisingly won a by-election as a Liberal candidate ahead of the 1979 general election, has had experience of political coalition from the 1980s and the Liberal-SDP Alliance.

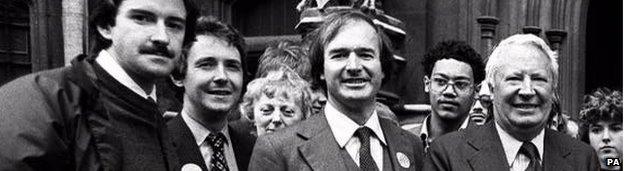

Lord Alton, second left, pictured in 1980 with Peter Mandelson, left, and Ted Heath, right

He was not keen on the two parties merging in 1988 to form the Liberal Democrats once it was clear SDP leader David Owen was not going to join - the electorate in 1983 and 1987 had seemed to like them being separate parties, he says.

But at least that coalition had been between two participants choosing to work together, rather than two parties being forced together as a "very hasty thing" a "shotgun marriage", he says.

Tactical votes

The SDP-Liberal Alliance came famously close to changing the course of British politics in 1983, gaining 25% of the vote, nearly overtaking Michael Foot's Labour.

Lord Alton says the first-past-the-post Westminster election system means that you need to get to 28% before support is properly recognised by the number of seats won.

"It's why people like [UKIP leader] Nigel Farage should be careful with polls - 28% is where it all changes."

Lord Alton, speaking before the recent allegations against Lord Rennard, said the future party strategist had cut his teeth as his election agent while still a student.

They had spent a lot time tackling the "wasted vote" argument, he added.

"Turning that tactical-vote argument became a significant part of what we had to do in the 1980s and it reaped rewards in the 1990s," he says.

"But those who live by tactical votes can die by it too - it's what you stand for that matters and I think the damage for the Liberal Democrats is that for a party that used to be seen to be standing for social justice, the party that stood for equality of opportunity and investment in education, to then vote for student loans... the damage is done."

Lord Alton says he has no lingering issues with the Lib Dems. He was sad that Charles Kennedy was "removed so brutally, he believes in a lot of the things I believe in and I felt he should have been given the chance of a sabbatical and the opportunity to come back to the leadership".

He has been impressed by Sarah Teather's "outspokenness" since being sacked as an education minister and he "likes" the look of some of the things Lib Dem president Tim Farron has been saying, but "I'm surprised that not more of them are speaking out in the House of Commons, because I hear what they are saying privately".

'Not a jihadist state'

For a long time after the Lib Dems were formed, it was easy to spot the former Liberals and the former Social Democrats but there has been "a morphing and I don't really know many of them any more", Lord Alton says.

"I'm still very close and admire Shirley Williams (ex-SDP) - her and my politics are much closer than, say, my politics and those of Paddy Ashdown (ex-Liberal who became Lib Dem leader)."

But he is now clear of party politics and able to pursue the issues and causes that he wants to as a crossbencher, or independent, peer in the House of Lords.

One of those causes at the moment is North Korea, a country he says the UK is "incredibly silent about" despite what he says are 200,000 people in "Gulags".

As chairman of the all-party parliamentary group on North Korea, he has invited dissidents to speak in Parliament and held a debate on the situation in the country. The day before we met, the North Korean ambassador had visited Lord Alton and asked him in no uncertain terms to stop holding parliamentary talks.

Despite the North Korean regime's evident irritation, they have hosted Lord Alton and parliamentary colleagues on visits to the country to see the situation for themselves.

"I pay my own way and write reports and practical proposals about what could be done," he says.

"This is not some jihadist state, it's an old-style despotic state and you only have to look at South Korea to see how it could be. I think we will see change in North Korea."

Lord Alton, who has experienced life as a backbencher and spokesman on a range of issues for the third party in the Commons also spent his final years as an MP on the Standards and Privileges Committee during the cash-for-questions inquiries.

Religion and politics

He is pleased to see the recent resurgence of the committee system at Westminster.

"Working with others on select committees on issues and pursuing causes was one of the most interesting and productive experiences in Parliament," he says.

"I've never liked yah-boo politics, I don't do it very well."

But he says he had most power during the time he spent as deputy leader of Liverpool council - "you used to be able to achieve a lot in local government and I think the emasculation of local government is a very negative thing".

Given his own experience, does he think it is possible to get to the top level of UK politics with strong religious beliefs?

"Some of our great political leaders, from all traditions - from Gladstone to Harold Macmillan to Kier Hardie - have had firm religious convictions. William Wilberforce was one of our greatest parliamentarians and it was his religious beliefs which led him to fight the evil of the slave trade," he says.

"I loathe theocracies, such as Iran. Despite its shortcomings I passionately believe in democracy.

"So, whether you have religious beliefs or not, in a secular society, you should simply fight for what you believe to be right and work to change attitudes, priorities and laws with which you disagree on the basis of winning the argument and winning the vote."

So, 33 years after entering Parliament, does he still believe politicians have the power to make the world a better place?

His answer is yes, but "I'm not a false optimist, I'm a realist I suppose".

"You have to do what you can to shape events. You can feel like that little boy in Robert Louis Stevenson's book who says, 'The world is so big and I'm so small I don't like it at all' and feel overawed, or you can say is there something specific I can do to try and make some small difference.

"That should be your motivation for going into politics. If a man waited until he was perfect before acting he'd wait for ever, so you do what you can where you can despite your own inadequacies."

- Published9 January 2013

- Published18 June 2012

- Published6 March 2012