UKIP: The story of the UK Independence Party's rise

- Published

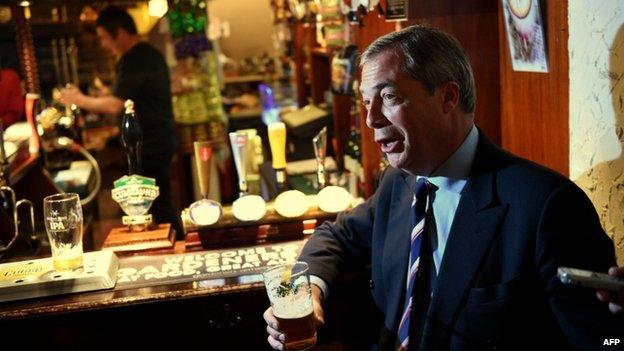

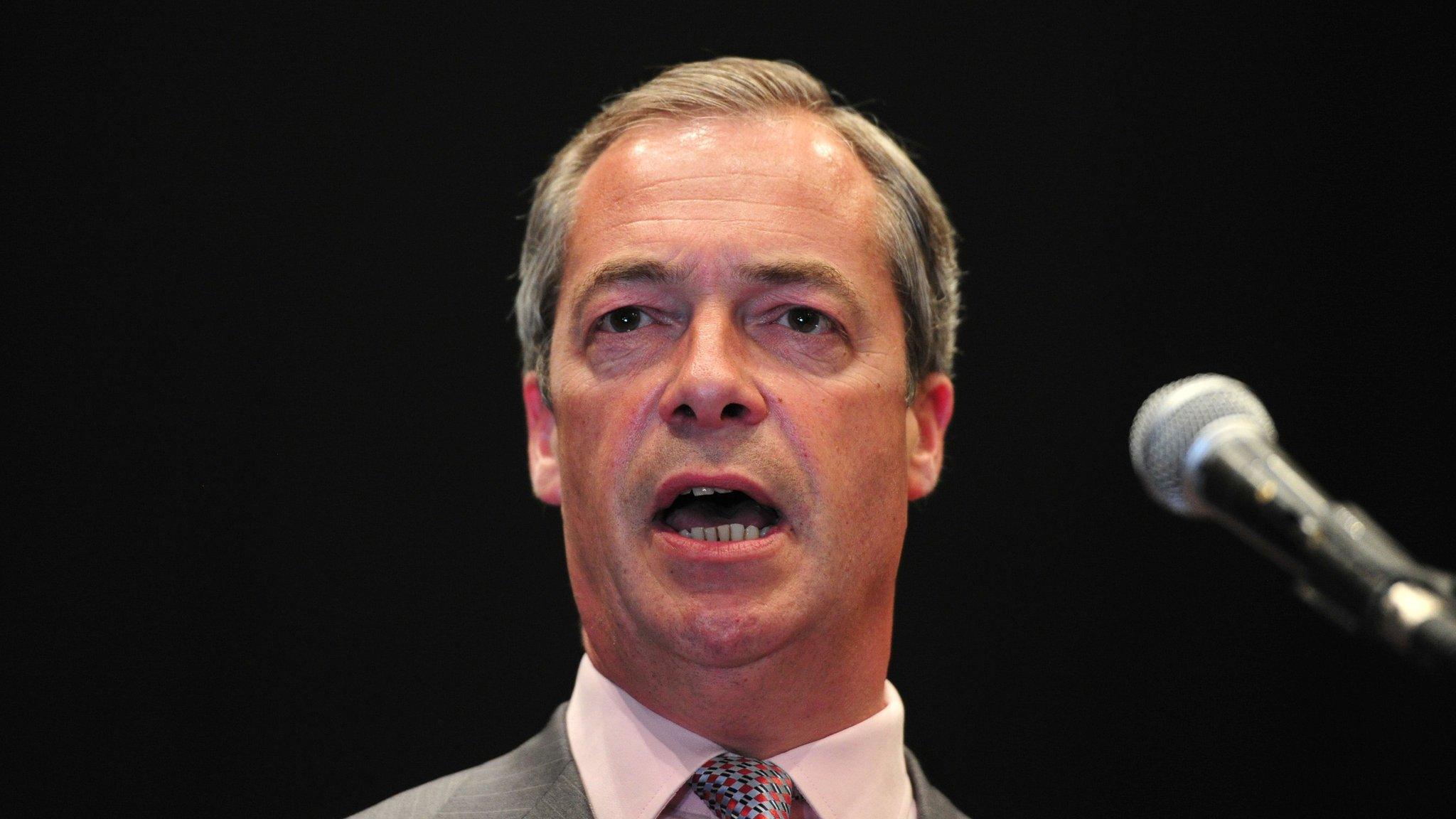

Nigel Farage was in jubilant mood as his party took its second Westminster seat

With its second elected MP at Westminster in as many months, the UK Independence Party has cemented its place as the new force in British politics. But its achievements are no overnight success.

The UK Independence Party has, as its name implies, one key policy - to leave the European Union.

It is a simple, understandable message, which has led to the party gaining bigger and bigger support in European elections, culminating in it topping the vote in May this year.

But it is also a message which meant people often dismissed it as a single-issue party, unlikely to transfer its success to Westminster politics.

It has spent considerable effort on broadening its appeal, spelling out how leaving the EU is the answer to a whole range of issues, notably controlling immigration, while also outlining plans to cut taxes for middle earners, speaking up for grammar schools and opposing gay marriage.

And the message from leader Nigel Farage - if any party has been associated with one man it is UKIP and Farage - seems to have struck a chord with disenchanted voters from the "big three".

Nigel Farage enjoys an everyman image

It became clear in the 2013 Eastleigh by-election that UKIP, rather than Westminster's official Labour opposition, seemed to have become the party of choice for the anti-government vote and the anti-politics vote.

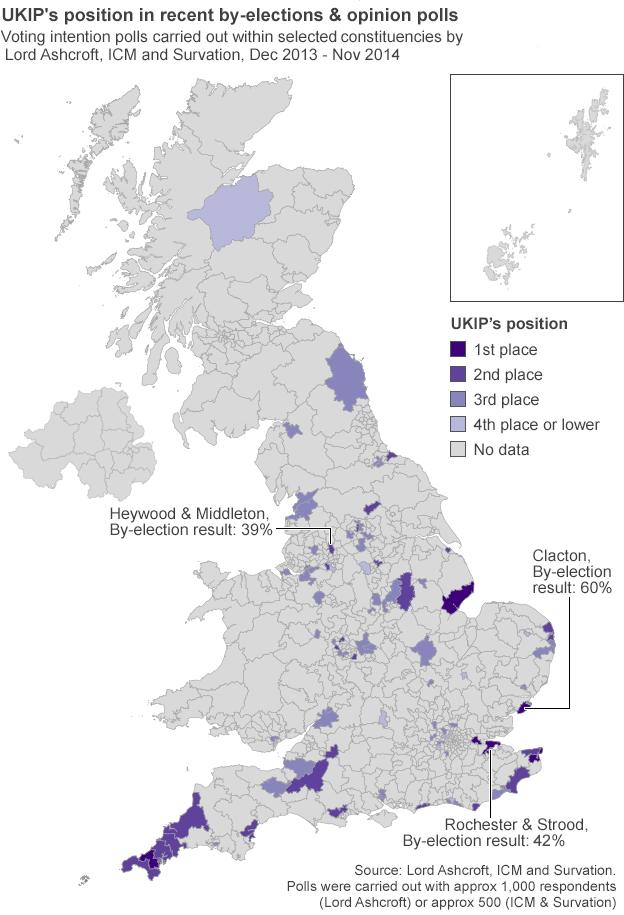

It has since proved capable of causing upsets in local elections in Tory and Lib Dem heartlands in the South of England and, as the South Shields and Heywood and Middleton by-elections demonstrated, Labour strongholds in the North. Its crowning moment came in October, when the party won its first Westminster seat, after the Conservative MP for Clacton, Douglas Carswell, defected to Mr Farage's team.

UKIP's share of the vote in Westminster by-elections:

November 2014: 42.1%

October 2014: Clacton 59.75%

October 2014: Heywood and Middleton 38.7%

June 2014: Newark 25.9%

Feb 2014: Wythenshawe and Sale East 18%

May 2013: South Shields 24.2%

Feb 2013: Eastleigh 27.8%

Nov 2012: Rotherham 21.7%

Nov 2012: Middlesbrough 11.8%

Nov 2012: Croydon North 5.7%

Nov 2012: Manchester Central 4.5%

Nov 2012: Corby 14.3%

Nov 2012: Cardiff South and Penarth 6.1%

Mar 2012: Bradford West 3.3%

Dec 2011: Feltham and Heston 5.5%

July 2011: Inverclyde 1%

May 2011: Leicester South 2.9%

March 2011: Barnsley Central 12.2%

Jan 2011: Oldham East and Saddleworth 5.8%

UKIP has realised the hard way that it is not enough just to pitch up at a by-election with a loud hailer and some media-friendly stunts, it requires months, even years, of groundwork in the local area.

The party's campaigning effort has become far more professional and well-funded in the past three years as a result. It is learning the highly specialised discipline, once the domain of the Lib Dems, of winning elections.

But UKIP is no overnight success or, as it can sometimes seem from the ubiquity of Mr Farage on the airwaves, a one-man party.

It has had more twists and turns - and splits and schisms - in its 20-year history than many a soap opera, with an equally colourful cast of characters.

Nigel Farage, pictured at a party event in 1997

How UKIP became a political force

Small parties have a habit of disintegrating into internal warfare or being wiped out by the vagaries of the electoral system and political fashion - British politics has seen a few come and go over the years.

But UKIP managed to keep its show on the road and defy the predictions of those who were ready to write the party off as, in the often-quoted words of David Cameron, "fruitcakes and loonies".

The party was founded on 3 September 1993 at the London School of Economics by members of the Anti-Federalist League, which had been founded by Dr Alan Sked in November 1991 with the aim of running candidates opposed to the Maastricht Treaty in the 1992 general election.

UKIP's growing vote share in national elections:

1999 European elections 7%

2001 General election 1.5% (saved deposit in one seat)

2004 European elections 16%

2005 General election 2.3% (saved deposit in 38 seats)

2009 European elections 16.5%

2010 General election 3.2% (saved deposit in 100 seats)

2014 European elections 27.5%

Candidates must get 5% of votes cast to save their deposit

UKIP's early days were overshadowed by the higher-profile and well-financed Referendum Party, led by Sir James Goldsmith, which was wound up soon after the 1997 election.

The new party's initial successes were all in the proportional representation elections for the European Parliament - winning its first three seats in 1999 with 7% of the vote.

Fed-up with what they describe as a pro-European conspiracy among the major parties, the UK Independence Party believe that their time has come

It built on that in 2004, winning 12 seats and pushing the Lib Dems into fourth place. The 2009 poll saw its total grow to 13 seats, pushing Labour into third place with 16% of the vote.

And in 2014's European election the party lived up to its confident promise to top the vote, getting 27.5% of all those cast.

General elections, however, with their first-past-the-post voting systems, have been a different story and the party has failed to make the breakthrough it has been hoping for.

In 2001 it saved its deposit (that is, got at least 5% of votes) in just one seat. In 2005 it saved its deposit in 38 seats but lost its deposits in 451 others - costing about £225,500. Even its then leader, former Conservative MP Roger Knapman, could only poll 7% of the votes in Totnes, Devon.

Recognition factor

In 2010 it was led into the general election by Lord Pearson of Rannoch but again lost out, with just 3% of the vote across the UK, although there were signs of progress as it saved its deposit in 100 seats.

The party had hoped to make headlines after Mr Farage stood down as leader so he could take on Speaker John Bercow in Buckingham at the 2010 election - he did make the headlines but it turned out they were about a plane crash that almost cost Mr Farage his life, rather than election success.

Robert Kilroy Silk was the public face of UKIP in 2004, before forming his own party

A UKIP billboard from the European elections in 2009

He recovered from his injuries and returned to head the party later in the year, in the latest instalment of the colourful story of UKIP's leadership.

Original leader and UKIP founder Alan Sked quit before the 1999 European elections, after arguing the party should refuse seats in the "gravy train" of the Strasbourg Parliament.

Shortly after that, the national executive lost a no-confidence vote and leader Michael Holmes resigned, although he remained an MEP.

Mr Knapman took over the role of leader in 2002, but in 2004, a new pretender to the crown - former Labour MP and chat show host Robert Kilroy-Silk - arrived in a flurry of media publicity to shake things up once again.

Before long he was openly jockeying for the leadership and was the media face of the party for the 2004 European election success - but when Mr Knapman refused to stand aside for him, Mr Kilroy-Silk quit and formed his own short-lived rival party.

Some thought that without Mr Kilroy-Silk's recognition factor the party might struggle.

Farage returns

In 2006, the lower-key Mr Knapman retired, to be replaced by Nigel Farage, an eye-catching media performer who pledged to make UKIP a "truly representative party", ending its image as a single-issue pressure group.

He spearheaded its success at the 2009 European elections and raised UKIP's profile, but surprised his own party conference in September that year by standing down as leader.

Mr Farage says UKIP is not just a threat to the Conservatives, but is "parking our tanks on the Labour Party's lawn".

Mr Farage said he would instead run for a seat in the Commons - specifically the seat of Commons Speaker John Bercow, which, by convention, other major parties do not fight. Mr Farage said it was "very important that UKIP gets a voice in Westminster".

Eton-educated Lord Pearson was Mr Farage's choice to replace him - but the peer never seemed at home in the job - for instance, admitting at the 2010 general election manifesto launch that he was not quite across the party's policy detail.

Mr Farage continued to be the highest-profile UKIP member - making headlines, and a viral video success, after telling the in-coming president of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, that he had "the charisma of a damp rag".

Following the 2010 election, when the party failed again to turn European into UK political success, Lord Pearson announced in August 2010 that he was stepping down, saying he did not enjoy party politics. Five hopefuls entered the race to succeed him, with Mr Farage triumphing.

'I'm a bit odd'

From that point onwards the party has seen its poll ratings rise, overtaking the Lib Dems and staying above them in most polls, and putting in increasingly stronger showings in by-elections.

David Cameron's historic pledge to hold and an in/out referendum on UK membership of the EU if the Conservatives won the next election was interpreted by some as an attempt to halt the rise of UKIP, which senior Tories feared could prevent them from winning an overall majority in 2015.

UKIP membership figures:

2002: 9,000

2003: 16,000

2004: 26,000

2005: 19,000

2006: 16,000

2007: 15,878

2008: 14,630

2009: 16,252

2010: 15,535

2011: 17,184

2012: 20,409

2013: 32,447

If that was Mr Cameron's plan, it does not appear to have worked.

Mr Farage criticised the decision to delay the vote by five years, and claimed the prime minister's promise showed "we have changed the political agenda in this country" calling it "our proudest achievement to date".

How UKIP became a political force

Asked what he would do if the British people voted to remain in the EU, Mr Farage joked that he would have to get a "proper job". But the party's success in local elections suggests it might have a future, even without the European issue, as a libertarian, right wing alternative to a centrist Conservative Party.

UKIP appears to have struck a chord with many voters on the issue of immigration, which was the focus of its European election campaign this year and an issue frequently raised by people saying they were going to vote for them ahead of the Rochester and Strood by-election.

It has rejected claims that it is simply "against" foreigners, arguing that it is in favour of a sensible "managed" migration policy, something Mr Farage argues is not possible while Britain remains in the EU. However, the party found itself in hot water over the issue a few days before its Rochester win, when is candidate, Mark Reckless, suggested EU migrants would only be allowed to stay in the UK for a fixed period if the UK left the European Union.

Those remarks were clarified later by UKIP, to reject the idea EU citizens faced deportation, and Mr Reckless later said he had been misquoted.

The party says leaving the EU is the only way to be able to control who moves the UK from Europe and says it would boost the UK's border force to crack down on illegal immigration. They would also change the law so that those without identifying documents can be sent back to the country they travelled from.

Although it is widely said to have gained support as a result of its tough talk on immigration - something pointed out by Nottingham University professor Matthew Goodwin in a book charting UKIP's rise - it has also been a key part of Nigel Farage's strategy to distance the party from the far right - its constitution bans former BNP members from joining.

Matthew Goodwin says UKIP's message has changed from one just about the EU to one with immigration and anti-Westminster establishment at its heart

Mr Farage's maverick style - his fondness for a pint of beer, disarming frankness and ability to laugh at himself - has given him a similar kind of appeal to voters as Boris Johnson, who has described the UKIP man as "a rather engaging geezer". But higher prominence has brought greater scrutiny, and earlier this month Mr Farage was forced to clarify his position on the NHS after a video of him appeared in which he suggested a publicly funded health service be replaced by a private insurance model.

Despite his background being, on paper, identical to many a politician, the message from focus groups and voters is that he is "different", not one of "them" at Westminster.

UKIP will hope to avoid the fate of the SDP in 1980s, which won by-elections, and soared in polls but in the end failed to translate that into a large chunk of Westminster seats

He told BBC Radio 4's Today in 2013 that he was "odd" but only in the sense that it was "odd" to be a politician "not doing this for a career... I'm here as a campaigner. I want to free this country from the European Union and then I want us to have a much smaller level of state interference in our lives in this country".

For much of its life UKIP has been seen as attracting Tories unhappy with the party, especially the Conservatives' move towards the centre under David Cameron and the current coalition government. Mr Farage says there are now "three social democratic parties".

There have also been more recent signs of gains from Labour, with UKIP seeming to get support from the same sort of anti-Westminster, anti-politics vote as Alex Salmond's Yes campaign in the recent Scottish referendum.

In that Today interview Nigel Farage said UKIP did not have any MPs because "the first-past-the-post system is brutal to a party like us".

That may have been so at past general elections - but winning in Clacton and now Rochester and Strood shows it is no longer just in European elections that UKIP is a force to be reckoned with.

- Published26 May 2014

- Published26 May 2014

- Published26 May 2014