Are conspiracy theories destroying democracy?

- Published

- comments

The more information we have about what governments and corporations are up to the less we seem to trust them. Will conspiracy theories eventually destroy democracy?

What if I told you I had conclusive proof that the moon landings were faked, but I had been told to keep it under wraps by my BBC bosses acting under orders from the CIA, NSA and MI6. Most of you would think I had finally lost my mind.

But, for some, that scenario - a journalist working for a mainstream media organisation being manipulated by shadowy forces to keep vital information from the public - would seem entirely plausible, or even likely.

We live in a golden age for conspiracy theories. There is a growing assumption that everything we are told by the authorities is wrong, or not quite as it seems. That the truth is being manipulated or obscured by powerful vested interests.

And, in some cases, it is.

'Inside job'

"The reason we have conspiracy theories is that sometimes governments and organisations do conspire," says Observer columnist and academic John Naughton.

It would be wrong to write off all conspiracy theorists as "swivel-eyed loons," with "poor personal hygiene and halitosis," he told a Cambridge University Festival of Ideas debate.

They are not all "crazy". The difficult part, for those of us trying to make sense of a complex world, is working out which parts of the conspiracy theory to keep and which to throw away.

Mr Naughton is one of three lead investigators in a major new Cambridge University project, external to investigate the impact of conspiracy theories on democracy.

The internet is generally assumed to be the main driving force behind the growth in conspiracy theories but, says Mr Naughton, there has been little research into whether that is really the case.

He plans to compare internet theories on 9/11 with pre-internet theories about John F Kennedy's assassination.

Like the other researchers, he is wary, or perhaps that should be weary, of delving into the darker recesses of the conspiracy world.

"The minute you get into the JFK stuff, and the minute you sniff at the 9/11 stuff, you begin to lose the will to live," he told the audience in Cambridge.

Like Sir Richard Evans, who heads the five-year Conspiracy and Democracy project, he is at pains to stress that the aim is not to prove or disprove particular theories, simply to study their impact on culture and society.

Why are we so fascinated by them? Are they undermining trust in democratic institutions?

David Runciman, professor of politics at Cambridge University, the third principal investigator, is keen to explode the idea that most conspiracies are actually "cock-ups".

"The line between cock-up, conspiracy and conspiracy theory are much more blurred than the conventional view that you have got to choose between them," he told the Festival of Ideas.

"There's a conventional view that you get these conspirators, who are these kind of sinister, malign people who know what they are doing, and the conspiracy theorists, who occasionally stumble upon the truth but who are on the whole paranoid and crazy.

What constitutes a conspiracy theory?

"Actually the conspirators are often the paranoid and crazy conspiracy theorists, because in their attempt to cover up the cock-up they get drawn into a web in which their self-justification posits some giant conspiracy trying to expose their conspiracy.

"And I think that's consistently true through a lot of political scandals, Watergate included."

'Curry house plot'

It may also be true, he argues, of the "vicious" in-fighting and plotting that characterised New Labour's years in power, as recently exposed in the memoirs of Gordon Brown's former spin doctor Damian McBride.

The Brownite conspiracies to remove Tony Blair were "pathetically ineffectual" - with the exception of the 2006 "curry house" plot that forced Blair to name a departure date - but the picture painted by Mr McBride of a "paranoid" and "chaotic" inner circle has the ring of truth about it, he claims.

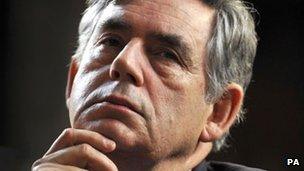

Gordon Brown was a keen student of conspiracy theories

And Mr Brown - said to be a keen student of the JFK assassination - knew a conspiracy when he saw one.

"You feel he sees conspiracies out there because he has a mindset that is not dissimilar to the conspiracy theorists," said Prof Runciman.

He is also examining whether the push for greater openness and transparency in public life will fuel, rather than kill off, conspiracy theories.

"It may be that one of the things conspiracy theories feed on as well as silence, is a surfeit of information. And when there is a mass of information out there, it becomes easier for people to find their way through to come to the conclusion they want to come to.

"Plus, you don't have to be an especial cynic to believe that, in the age of open government, governments will be even more careful to keep secret the things they want to keep secret.

"The demand for openness always produces, as well as more openness, more secrecy."

Which brings us back to the moon landings. I should state, for the avoidance of any doubt, and to kill off any internet speculation, that I am not in possession of any classified information about whether they were faked or not. My contacts at Nasa are not that good.

But then I would say that wouldn't I?

- Published8 October 2013

- Published9 March 2012

- Published29 August 2011