David Cameron promises Sri Lanka 'tough message' on alleged war crimes

- Published

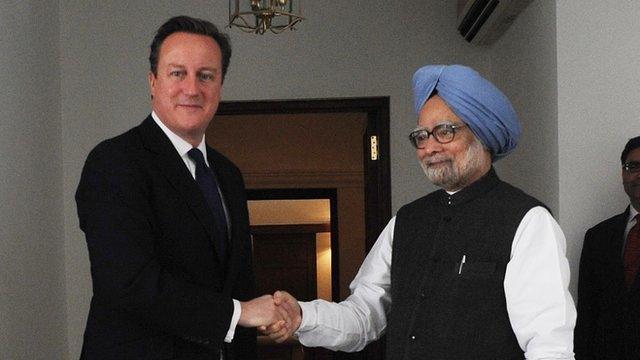

Prime Minister David Cameron: "There are legitimate accusations of war crimes"

David Cameron has promised to send a "tough message" to Sri Lanka's government over alleged war crimes after it warned him not to question ministers at the Commonwealth summit.

The UK prime minister, who has rejected calls to boycott the meeting in Colombo, said there had to be "proper inquiries" into events in 2009.

But Sri Lanka's government said he had no right to bring up the subject, as he had not been invited on that basis.

The conference begins on Friday.

The Prince of Wales, who celebrated his 65th birthday on Thursday, is representing the Queen at the biennial event.

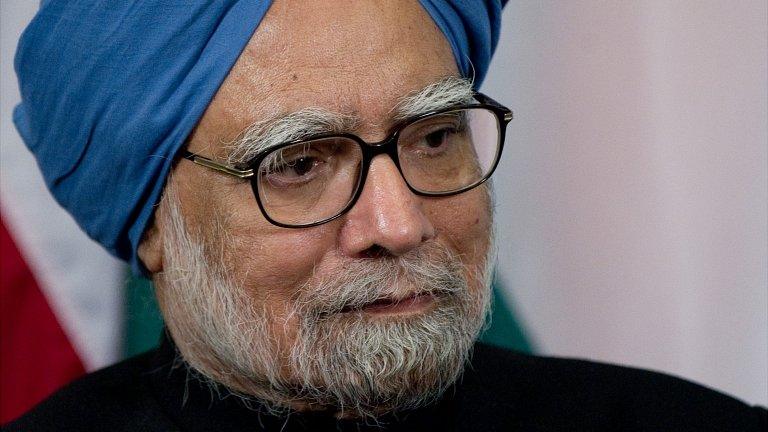

Mr Cameron's attendance follows trade talks in New Delhi with his Indian counterpart, Manmohan Singh, who is among those avoiding the event.

'Appalling'

Mr Singh is joined by the prime ministers of Canada and Mauritius, who are staying away in protest over allegations that the regime of Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaska carried out war crimes at the end of a civil war with Tamil separatists four years ago.

The UN estimates that 40,000 civilians were killed in the last five months of the 26-year conflict, but the Sri Lankan authorities deny responsibility.

In an interview with the BBC's Nick Robinson, Mr Cameron said: "There are legitimate accusations of war crimes that need to be properly investigated.

"That is actually what the Sri Lankan government, in its own lessons learned and reconciliation exercise, found - there were more questions to be answered. But it hasn't effectively answered them. They need to be answered.

"We should be clear, this was an appalling civil war, a civil war in which obviously the Tamil Tigers, using suicide bombs and child soldiers, did some appalling things as well.

"But the end of the war, and this particular set of events where civilians seem to have been targeted - that needs to be properly investigated."

'Independent state'

Tamil representatives and Labour, the British opposition party, urged Mr Cameron to join the boycott, but he argued he could achieve more by using his attendance to "shine a spotlight" on "some of the human rights issues".

But the Sri Lankans reacted angrily to that suggestion.

"The invitation to Prime Minister David Cameron was not based on that," minister of mass media and communications Keheliya Rambukwella told the BBC.

"We are a sovereign nation. You think someone can just make a demand from Sri Lanka?

"We are not a colony. We are an independent state."

Asked about the comments, Mr Cameron maintained he was right to raise questions, adding: "That's exactly what I'll be doing."

Although he said he wanted to deliver a "tough message" to the Sri Lankan government, he pledged not to be "completely uncompromising".

Mr Cameron explained: "There are some positive steps that have been taken in Sri Lanka: the fact that they had elections to a northern provincial council; the fact that there is a process of reconciliation, it's just not going as far as we would like it to go.

"So on the ledger, there are some things on the positive side, but there are too many things on the negative side. Now that's a frank conversation I think we should be able to have."

British media in Sri Lanka who have been asking questions about the government's human rights record have struggled to get answers.

A Channel 4 documentary team was forced to give up on reaching the north of the south Asian state after being stopped by pro-government demonstrators.

'Deep concerns'

A BBC cameraman was physically restrained by security officials at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting as he and correspondent James Robbins were attempting to film Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa at a media event before the formal opening.

The BBC's James Robbins says David Cameron is determined to put Sri Lanka's human rights record in the spotlight

Labour leader Ed Miliband said: "My party has been clear that in our view we believe that this lamentable human rights situation meant that the British prime minister - like the Canadian and Indian prime ministers - should not attend the summit."

But Mr Cameron, having decided to attend, must now "insist on the full implementation of the recommendations of Sri Lanka's own Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission", Mr Miliband argued, in an article for the Tamil Guardian, external.

He also urged the UK prime minister to "seek urgent assurances from the Sri Lankan authorities" that they will respect the Commonwealth's values on human rights as they respond to any protests that may take place during the forthcoming summit.

Labour's shadow foreign secretary Douglas Alexander was blunter, telling the BBC: "The prime minister has blundered, and blundered badly, in his decision to attend the summit."

Mr Cameron, who arrived in Delhi on Wednesday en route to the summit, has met Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

The UK PM has hailed "extraordinary progress" on trade and investment since his first visit in 2010, and pledged to "cement Britain as India's partner of choice".

He is also seeking to reassure Indian nationals about his drive to cut immigration to the UK.

- Published14 November 2013

- Published14 November 2013

- Published14 November 2013

- Published13 November 2013

- Published10 November 2013

- Published18 November 2019