Shadows over Commonwealth summit in Sri Lanka

- Published

Sri Lanka has invested a lot in sprucing up the capital ahead of the Commonwealth summit

The streets of Colombo are glistening for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (Chogm). But controversy still rages over war crimes allegations, press freedom, judicial independence and the safety of minorities. The BBC's Charles Haviland reports on the rights issues that refuse to go away.

New fountains are flowing, there are new pavements and new street lamps have been constructed. A motorway has just opened linking the airport to Colombo for the first time.

Colombo's violence-scarred past is becoming a mere memory. Many Sri Lankans are proud to be welcoming the Commonwealth leaders and see the summit as a tribute to a president many revere for his victory after 26 years of conflict with separatist Tamil Tigers.

But for all the burnished infrastructure, there is disquiet under the surface.

The summit's attendance list has narrowed, with Canada's Prime Minister Stephen Harper boycotting the event over rights abuses. Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has also said he will not attend.

Army demolition spree

Visiting the Northern Province during its recent election, the BBC met 37-year-old Sujitharan in a refugee camp outside Jaffna.

The children played in the dirt. The place felt temporary, prefabricated. Yet Sujitharan has been here since 1990 when his family fled their home because of fighting between the government and the Tamil Tigers (LTTE).

The military keeps hold of their land, like other large tracts deemed high security zones.

"We're living as second-class citizens with no facilities, no bathrooms. It's a very sad life. Our children need to live on their own land," he says.

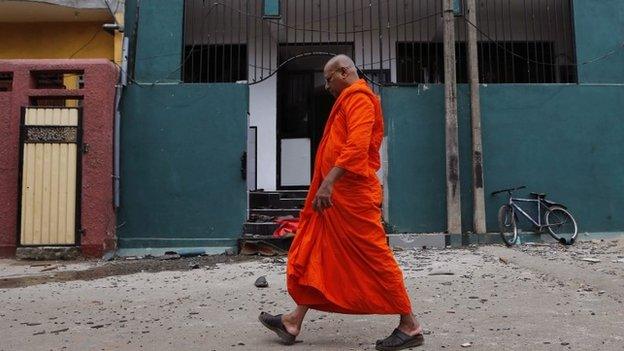

Mosques and Muslims have also been targeted over the past year by some hardline Buddhist groups

Sujitharan had decided to vote for President Rajapaksa in the hope of getting his land back.

But in recent days - after the Tamil opposition's election victory in the North - the Sri Lankan Army has gone on a demolition spree, flattening the houses of people displaced long ago to consolidate these zones - which it says it needs "for security reasons".

When journalists try to film or photograph it, their memory cards are seized and deleted and they are chased away. The demolitions continue.

Then there are the unanswered question about possible war crimes and allegations of the indiscriminate bombardment of Tamil civilians as the war ended; of the summary killing of the captive LTTE members who surrendered.

Grave war crimes accusations are also levelled at the LTTE, but as most of them did not survive, and as the Sri Lankan government has continued to justify its conduct, the spotlight is focused on the current leaders.

Minorities targeted

The BBC's Fergal Keane reports from Sri Lanka on alleged attacks on journalists and activists

Journalists and human rights workers continue to report intimidation. A BBC correspondent based in northern Sri Lanka was recently questioned for hours by the anti-terrorism police.

A senior Colombo-based journalist fled the island after two raids on her home: During one, she and her family were threatened at knifepoint.

Disappearances remain unsolved and allegations of torture in state custody - often backed by forensic evidence - continue to emerge.

And members of religious minorities are being attacked in a trend boosted by the war victory.

The spate of assaults on Muslims and demonstrations against them by Sinhalese Buddhist hardliners have been well reported.

But now Christians are coming forward to report attacks which have long been happening, but local media barely mention then.

The remains of a church burnt down by a mob in Batticaloa

In Colombo I meet a pastor from a small church. He does not want his name used and is here because he is afraid to receive me in his village.

"Two Buddhist monks rushed into the church," he says in Sinhala, recounting a recent incident during a service.

"Twenty-five or 30 villagers followed. They yelled insults at us, calling us traitors for preaching the word of God. They shouted 'this is a Buddhist nation, a Buddhist village'.

"They threatened to kill us, they said they would burn my house down when they came back."

He says the monks started physically assaulting him. He knelt down facing the wall and prayed.

The clergyman is from Sri Lanka's Sinhalese majority - Christians straddle the ethnic divide.

The pastor says he has since seen the monk who led the attack on television with President Rajapaksa. He was able to identify the attackers but says the police told him that if any of the attackers were arrested that would create religious controversy and an ugly scenario.

Yamini Ravindran of the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of Sri Lanka (NCEASL) has documented 65 attacks on Christians so far this year.

"Pastors have been threatened, subjected to duress and forced closure of churches, various forms of discriminations... And even some Christian believers have been forced to recant their faith."

Minorities feel uneasy because the government rarely condemns such assaults or apprehends the culprits. Hindus, who are Tamil, are in a similar situation.

The government recently demolished a small Hindu temple in the town of Dambulla, in an area the authorities have declared sacred to Buddhists.

A Tamil politician, N Kumaraguruparan, says the Hindus appealed to President Rajapaksa against the demolition, then asked for time to perform final religious rites. Both appeals went unheeded.

In a recent visit to Sri Lanka, the UN's human rights chief, Navi Pillay, criticised what she called the "surge in incitement of hatred and violence against religious minorities... and the lack of swift action against the perpetrators".

The government denies committing war crimes or trampling on human rights.

Secretary-general Kamalesh Sharma says the Commonwealth's strength is "engagement"

Peaceful co-existence

Udaya Gammanpila, a provincial minister from a Buddhist nationalist party in the government coalition, says Canada's leaders should come to Chogm, like their counterparts.

"The reality is that Sri Lankans, as one family, we are trying to live together after a long civil war... If they just come to Colombo and go around they will find the co-existence of Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims."

The Sri Lankan state often stresses the co-operation between the island's four major religions. In the cities, churches, mosques and Buddhist and Hindu temples sit side by side, with many devotees never facing problems.

And it is certainly true that in Colombo you do find communities mixing quite happily - but critics say this should not mask deeper divisions and concerns.

So what about the pastor's account of the church attack?

"Frankly we are not aware of such incident," said Mr Gammanpila, adding that the victim could have complained to the Supreme Court if he felt the forces of the law were not doing their job.

President Rajapaksa is seen as a hero by many majority Sinhalese, for ending years of war

Mr Gammanpila also seemed unaware of the 65 attacks documented by the NCEASL, saying the accounts might be "made up" by the Christians.

I asked him about Navi Pillay's assertion that Sri Lanka was drifting towards authoritarianism with the sacking of the former Chief Justice Shirani Bandaranayake and allegations of widespread impunity.

Mr Gammanpila said this was "expected" as Ms Pillay was "from a Tamil ethnic origin. She was biased towards her community in the first place."

While in Sri Lanka Navi Pillay, who is South African, deemed such remarks incorrect and offensive. Nor is the sacked chief justice from the Tamil community. But Mr Gammanpila insisted the UN rapporteur had no right to look at the Sinhalese-Tamil conflict.

The Sri Lankan government does get solid support from many other Commonwealth states, especially in Asia and Africa, who do not want the organisation to intervene in human rights.

But as the summit gets under way - minus several key leaders - it seems to be less about the actual Chogm agenda than about the host country and whether it lives up to the Commonwealth Charter.

- Published13 November 2013

- Published9 November 2013

- Published21 November 2019

- Published18 November 2019

- Published10 November 2013

- Published7 October 2013

- Published9 January 2015

- Published24 August 2017

- Published31 August 2013