A guide to life in a marginal constituency

- Published

How do you know you are living in a marginal constituency?

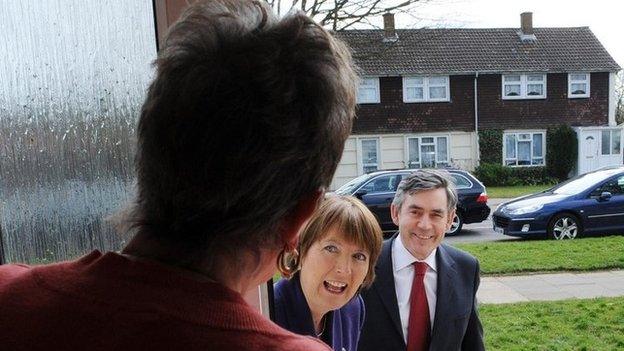

One clue is when you get a surprise visit from a top politician.

And it's no good pretending to be out - because the phone calls are about to start too. And the leaflets.

Over the next 16 months you are going to be bombarded with glossy pamphlets and newspapers packed with pictures of grinning election candidates.

Interactive: The seats which could decide the next election

If you manage to get your front door open, you might start to wish you had moved house, but you are, in fact, one of the lucky ones.

You are part of a select band of people who will decide the outcome of the next general election.

Marginal constituencies are those where the local MP won his or her seat by a relatively narrow margin. About 5,000 votes or less, although there is no hard and fast definition.

There is no real logic behind where they are located either.

Targeting

There have always been a lot of marginal seats in the Midlands - where traditional Labour Party heartlands bump up against true blue Conservative country.

But in other areas it might come down to local factors - how popular the sitting MP is or how the constituency boundaries have been drawn.

In non-marginal areas, where the local MP has a healthy majority, you will barely notice an election is happening at all until a few weeks before polling day in May 2015.

It is not that the parties don't want your vote exactly, it is just that they have to concentrate their limited resources on seats where they stand a realistic chance of winning.

It's called targeting, and all the parties do it.

They have software that seeks out the people likely to be most susceptible to their message. At the 2010 general election, the Conservatives used Merlin, based on the Mosaic database sold by credit reference agency Experian. It divides voters into 65 consumer "tribes" such as "café bar professionals" or "overstretched young aspirers".

The parties can then target their leaflets and phone calls at the right people.

Biggest complaint

They know where you live. And they will print up leaflets for every conceivable type of voter - from party loyalists who might need a bit of a push to get off their sofa "(don't let Labour/The Tories back in!") to those who have always supported the other side but might, at a pinch, be persuaded to change.

Campaign teams are making more use of social media but leaflets are still seen as the most effective way of communicating with voters - apart from a visit from the candidate, that is.

The personal touch counts for a lot - the biggest complaint campaigners hear on the doorstep is that they have not had not seen anything of the man or woman who wants their vote.

Sometimes the party leader, or another leading light, will descend on a marginal constituency to knock on some doors, or join volunteers at the phone bank to put some calls into startled householders.

Every vote counts in a marginal - as Tory MP and spy novelist Rupert Allason discovered to his cost in 1997.

According to newspaper reports, Mr Allason lost ultra-marginal Torbay because he failed to tip a pub waitress a week before polling day. Fourteen Tory-voting waiters switched to the Lib Dems in protest. And Mr Allason lost his seat by 12 votes.

There are plenty of other stories of candidates who missed out by the tiniest of margins.

Hard to predict

But the biggest headache for campaign managers is the three or four-way marginal.

In the 1950s, the high water mark of the two-party system, more than 90% of voters cast their ballot for Labour or the Conservatives.

But as old tribal loyalties have melted away, and new, smaller parties have sprung up, things have become much more complicated and hard to predict.

In 2010, the constituency that saw the most money spent on campaigning was Luton South, in Bedfordshire, according to research by The Electoral Reform Society, external.

This was not at the top of anyone's target list but it was a three-way marginal, with Labour, the Tories and Lib Dems all believing they were in with a shout.

It was further complicated by the fact that the sitting Labour MP, Margaret Moran, had been convicted of expenses fraud and TV celebrity Esther Rantzen was running a well-funded campaign (she outspent the Lib Dem candidate).

In the end, the 12 candidates spent a total of £129,687 - which worked out at £3.07 per vote. Labour retained the seat.

Tight shortlist

At the other end of the scale, in ultra-safe Labour seat Bootle, on Merseyside, the parties spent 14p per vote. The Conservative Party spent nothing at all.

Leaflets have always been a key part of any general election campaign

The Electoral Reform Society believes that this proves the fundamental unfairness of a system in which only a few thousand people have any real say in the outcome.

Others argue that the British electoral system is far more diverse and unpredictable than that.

Research by the Centre for Policy Studies, external, ahead of the 2011 referendum on changing the voting system, suggested 85% of constituencies representing about 39 million voters are either marginal or give voters a reasonable chance of changing their MP.

Whatever the case, the parties will still be focusing all of their efforts on a tight shortlist of the most winnable seats.

The 2015 election is expected to be the closest in decades and they simply cannot afford to take any chances.