Cutting immigration will fuel debt, Chote warns ministers

- Published

David Cameron says net migration is too high and must be reduced

Britain's debt is likely to go up if David Cameron meets his key immigration target, the government's independent economic forecaster has warned.

No 10 wants to cut net migration into the UK to below 100,000 a year by 2015.

But Robert Chote said this would result in a "somewhat worse" fiscal position.

He told MPs that immigration boosted national income because migrants were more likely than native Britons to be of working age and less likely to use benefits, pensions and healthcare.

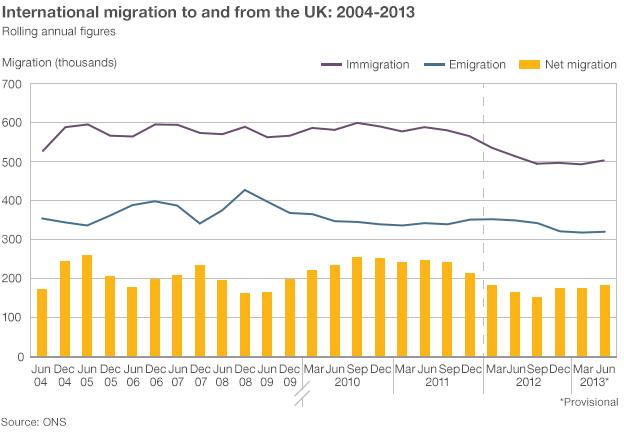

Net migration, the difference between the number of people leaving the UK and those coming to live here, rose sharply under the last Labour government, peaking at more than 250,000 in 2010.

The Conservatives have pledged to reduce annual totals to the "tens of thousands" by the end of the Parliament although, after falling for two years, net migration rose again to about 182,000 in the year to June 2013.

The target is not government policy as the Lib Dems do not back it - claiming it is arbitrary and may stop employers hiring people with specific skills.

Political debate over immigration has intensified in recent weeks as the government has announced curbs on access to benefits for new arrivals, and work restrictions on Bulgarians and Romanians in place since 2007 have expired.

Campaigners for tighter controls say the arrival of more than one million migrants from new EU members since 2004 has put a strain on the UK's labour market and public services but the European Commission has insisted that immigration has been broadly positive for the British economy.

'Cost of education'

Mr Chote, chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility, told the Commons Treasury Committee the body "did not have a view" about what was the ideal level of immigration for the health of the economy and the public finances.

But he said higher levels of net migration tended, over the long-term, to produce a "more beneficial picture in terms of the fiscal position".

"Essentially speaking, inward migrants are more likely to be of working age than the population in general," he said.

"They arrive after some other country has picked up the expense of educating them and in some cases - though not all cases - they leave the country again before you get to the point at which they are most expensive, in terms of pensions, healthcare and long-term care," he said.

Asked what the consequence would be for the public finances if the immigration target were met, Mr Chote told the committee: "The direction would be clear enough, because obviously you would have fewer net inward migrants, the fiscal position would be somewhat worse on those grounds."

Reducing debt as a share of GDP over time is one of the coalition's main economic targets.

The OBR has not produced a prediction for the impact of net migration falling below 100,000, because it relies on Office for National Statistics forecasts of population size, currently based on annual inflows of 200,000, 140,000 or zero.

But a member of the OBR's Budget Responsibility Committee, Prof Stephen Nickell, told the committee that an estimate approximately halfway between 140,000 and zero "would not be too far off" the correct figure.

The OBR predicted last year that public sector net debt would be just under 100% of GDP by 2063 if net migration continued at 140,000 a year, but would reach as much as 140% of GDP if it were reduced to zero.

This suggests that achieving Mr Cameron's target could increase the UK's state debt by around 20% of GDP over 50 years.

But Mr Chote acknowledged governments could counteract the effects of a shift in migration levels by changing policies in other areas such as tax and spending.

"There is no level of net inward migration you have to have for there to be fiscal sustainability," he added. "It's an influence on a whole variety of other choices government has to make."

- Published12 January 2014

- Published7 January 2014

- Published7 January 2014

- Published28 November 2013