TV political debates: Lessons from history

- Published

Nothing gets TV executives salivating - and political leaders quaking - like a live televised debate. Beneath the glare of the studio lights, a politician is at his most exposed.

One stumble, a flash of anger, an inappropriate joke, a memory lapse or just a failure to bring your "A Game", and the whole shooting match can be over. The fate of nations sometimes hang in the balance.

But the lessons are still there to be learned.

The first lesson is, um, er...

Rick Perry could not remember the third government department he plans to abolish if elected president - Footage courtesy of CNBC.com

Rick Perry the Texas governor was a much-fancied contender in the 2011 race for the Republican nomination. Then, in a TV debate, he decided to list the three government departments he would axe if he made it to the White House. Routine stuff. The trouble is, he could only remember two of them. And that was that for Perry's Presidential bid. He withdrew from the race shortly afterwards. So apart from being properly briefed on your own policies what else can we learn from the US, birthplace of the TV debate?

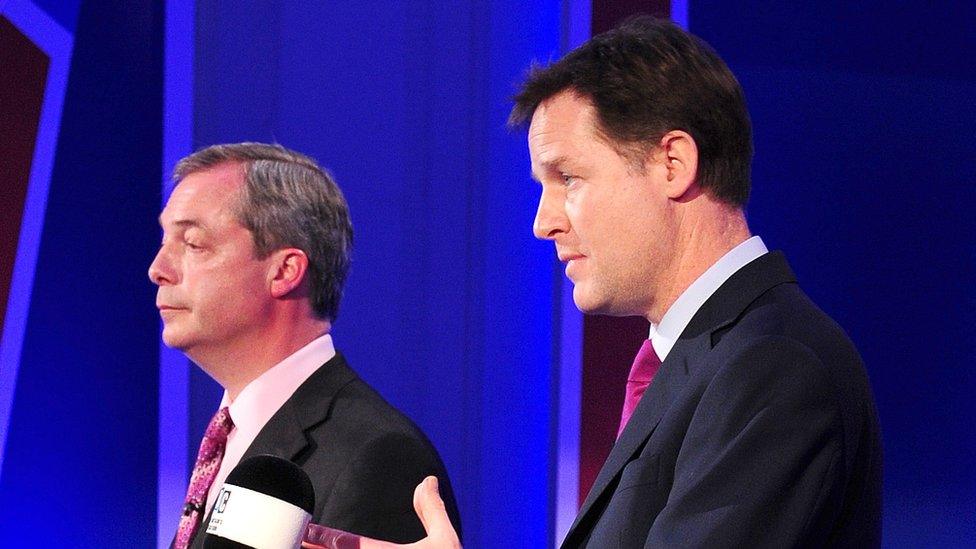

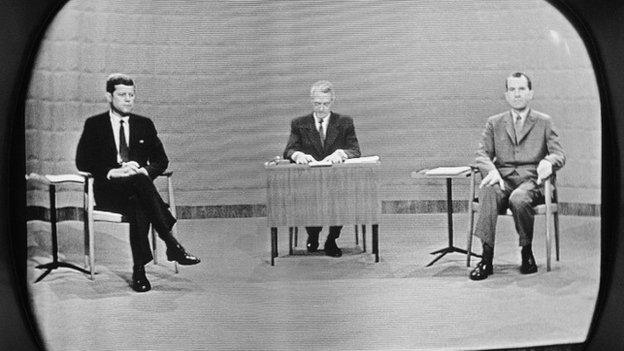

Don't sweat too much and try not to look shifty

John F Kennedy's 1960 televised debate with Richard Nixon is the most celebrated example of the genre. Vice-president Nixon started favourite - but he had been ill, and looked pale, withdrawn and unshaven alongside the telegenic Kennedy. Then he kept glancing, shiftily, up at the clock. Most of those following the debate on radio thought Nixon had come out ahead. Those watching on TV said the winner was Kennedy. The next lesson is even more obvious.

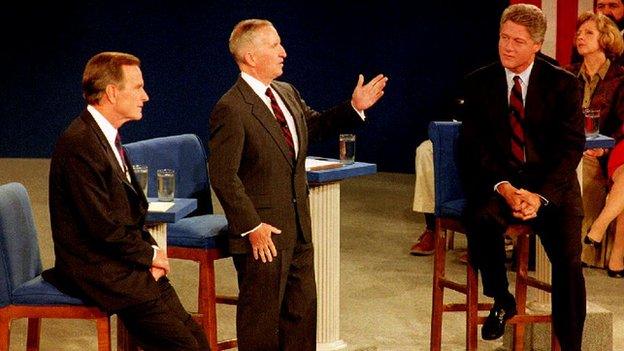

Don't patronise your opponent

George Bush Sr kept glancing at his watch during his 1992 debate against Bill Clinton and Ross Perot - giving the impression that he couldn't wait for it to be over. Al Gore's sighs while George W Bush gave his answers in 2000 were similarly damaging. The next lesson is a more positive one.

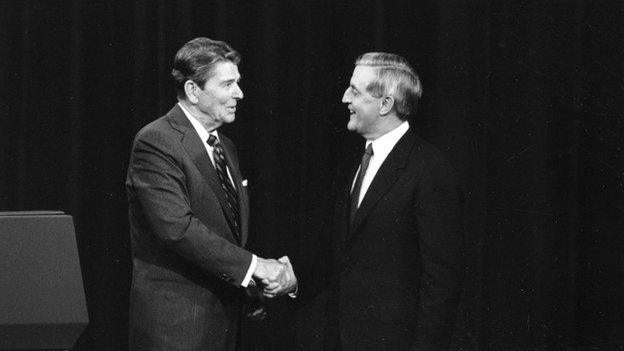

Have a few pre-scripted "zingers"up your sleeve,

"I will not make age an issue of this campaign," said Ronald Reagan in 1984 when asked if, at the age of 73, he was up to four more years in the White House. "I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience." Even rival Walter Mondale had to laugh at that one. A good joke tends to go down well, so...

Don't lose your temper

This is another obvious lesson. Although it can sometimes work if your opponent loses theirs too, as in the 2007 clash between French President Nicolas Sarkozy and challenger Segolene Royal (pictured above), which culminated in the pair yelling "Calmez-vous!" at each other. French viewers had never seen anything like it.

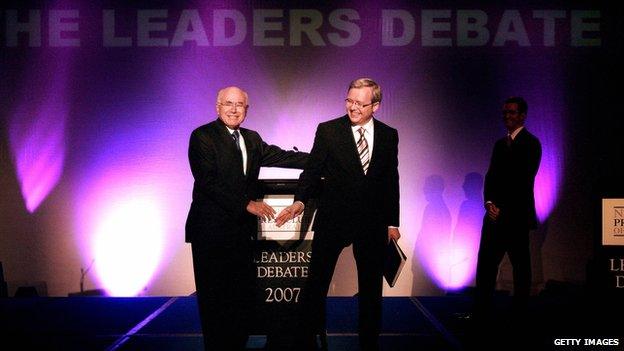

Beware gimmicks

In Australia, debate coverage is dominated by "The Worm," an electronic line that runs along the bottom of the screen controlled by a panel of floating voters. Politicians speak of the The Worm in awed tones. It can make or break them. In a 2007 debate between Kevin Rudd and John Howard there were even accusations of political skulduggery, with the "Worm Moderator" accusing Howard's ruling Liberal Party of sabotage. If there was foul play, it didn't work - Rudd went on to win.

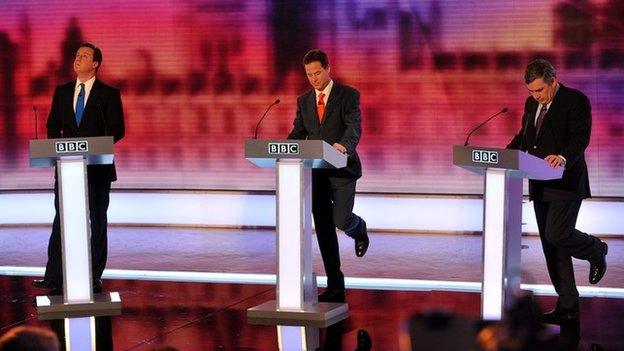

Watch out for the underdog

They have the least to lose. This was a lesson learned by Jimmy Carter in 1980, who refused to take part in a debate with John Anderson, a liberal Republican who was mounting an independent bid to eject him from the White House. Carter's Republican rival Ronald Reagan rose to the challenge, handing the little-known Anderson a TV audience of 55 million Americans. He got 7% of the vote on polling day though. The same lesson could apply to our own leader debates at the 2010 general election although Cleggmania had pretty much evaporated by the time polling day came around.

- Published31 March 2014

- Published26 March 2014

- Published26 March 2014

- Published26 March 2014