Miliband on Israel, PM plan and Thatcher comparison

- Published

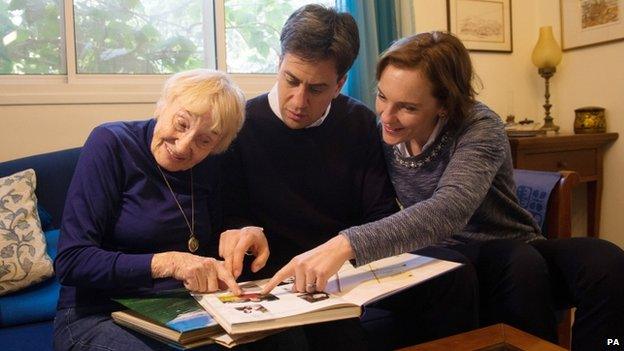

Ed Miliband was welcomed with open arms by his mother's cousin Sara in Israel

On a kibbutz outside Jerusalem Ed Miliband was greeted with a loud, warm Jewish embrace from 84-year-old Sara - his mother's cousin - who, like her, is a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust.

It marked the end of a visit to Israel that has been as much about the personal as the political - a chance for the Labour leader to connect with his past as well as to talk about the future of the Middle East.

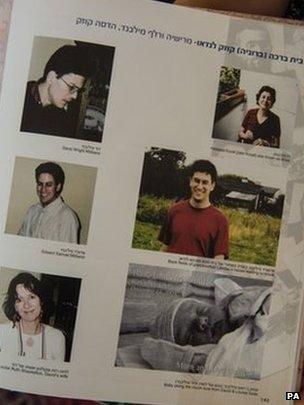

At the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial he was handed a book - the record of the lives and deaths at the hands of the Nazis of his relatives.

He gulped and his wife Justine fought to hold back tears when they discovered that his grandfather had apparently died, not in Auschwitz - as they'd always thought - but in another concentration camp.

I spoke to him about what the experience meant to him.

NR: "It was quite an emotional visit for you to the Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem. Did it bring you close to the losses your family suffered as a result of the Nazis?"

EM: "It was sort of awful if I am honest. It is awful because you see the suffering.

"It would be awful for anyone because you see the suffering, but it was particularly, incredibly painful for me.

"They presented me at the end a document - which I have got here - about my family history and about my grandfather, who I never met who died in one of the camps.

"I feel such a long way away from that family history in a sense, because I have led such a secure upbringing from a very stable family, but both my parents were refugees.

"Large numbers of their relatives - including my mum's dad - lost his life in the Holocaust and so it is part of who I am, but a long way away, and then to come so close to it is incredibly painful."

Mr Miliband said he felt a "long way" from his family's tragic past due to his own "stable" upbringing

NR: "For those people who don't have those family roots, just try and capture what it means. You are not a religious man, it is not a religious thing that you are talking about, so what is it and how does it affect a potential prime minister?"

EM: "There will be people who have lost relatives in very sad circumstances and so that is where it starts.

Mr Miliband saw family pictures including some of himself and his brother David

"But then it's about people whose lives have been broken, been dislocated, been sent hither all over the world.

"My dad [came] as a refugee to London in 1940, my mum [found] her way there after the Second World War.

"I think if I can say in a strange way that the only positive there is... having seen that broken world and broken families, I think it made them give me an upbringing which said 'don't waste a life, don't waste a single life'.

"So many lives have been wasted and destroyed, they never said that to me, so that is what is odd about it.

"They never said 'our family has a Holocaust history so you better work hard and do your homework', but they inculcated in me a sense of 'you have got to try and repair a broken world'.

"So that is - I won't say a positive - but that is some of the impact that it had on me."

Children play inside

Just how broken the Middle East is, Mr Miliband saw on the top of a hill just above the Gaza Strip.

He and his wife Justine were shown where the rockets are fired which rain down on this Israeli town of Sderot.

They visited a playgroup which looks like many you would see in the UK, until you realise the kids are playing inside instead of outside as they would not be safe under the deep blue sky and are only so under a roof of reinforced concrete.

Ed Miliband and his wife Justine looked to Gaza from Sderot in Israel

On a visit to the West Bank on Saturday he will hear of Palestinian suffering.

Ed Miliband now talks often of his Jewish heritage (though not faith because he is an atheist) but he has never been a cheer leader for Israel.

He's reluctant to call himself a Zionist.

In his first speech to his party conference after being elected Labour leader in 2010, he urged Israel to recognise in deed as well as word the Palestinians' desire for statehood.

I asked him to spell out what sort of foreign policy a Prime Minister Miliband would pursue.

EM: "I want to be the post-Iraq prime minister and that means learning the lessons of Iraq.

"It does mean a Britain engaged with the rest of the world, and willing on occasion in the right circumstances to play its part militarily, of course to defend itself, but also for other purposes.

"But with clear tests - that military intervention can only be justified as a last resort and if there is a clear and compelling case for making that intervention, if there is international support and there is a proper prospect of success.

"If you look at the decisions I have made as leader of the opposition on Libya, where I supported intervention, or on Syria where I opposed it, I think I have been consistent with those principles and they are principles that I would apply in government."

'Underestimated'

This visit is Mr Miliband's first major international trip apart from three visits to Afghanistan.

He has not visited the White House, Beijing, Delhi or Berlin as leader of the opposition.

"I will make other visits," he told me - but I put it to him that this underlined a problem many people thought he had.

Mr Miliband tells Nick Robinson the visit was "incredibly painful"

NR: "In little under a year's time you may be moving into 10 Downing Street. Do you accept that the British public don't yet see you as a prime minister, they can't yet envisage it?

EM: "I think it is maybe always the case with leaders of the opposition.

"I have been doing this job for three-and-a-half years and I think in the past that people have maybe underestimated me.

"I am looking forward to the next 12 months. I think it is a big fight for the future of the country."

NR: "You think you have always been underestimated?"

EM: "You always get your critics as leader of the opposition and I think people have tried to write us off before, but I am pretty confident and optimistic about the next election.

"I think there is a big fight for the future of Britain and about what kind of country we want to be like."

Back home, Mr Miliband has been under pressure not to play it cautious in his approach to the next election and to be true to himself as the man who became Labour leader because he represented a rejection of his party's recent past.

NR: "There are some who accuse you of being simply too cautious as you are running for the election. I sense there is a kind of radical trapped in there, you want to see yourself as another Attlee or Thatcher, is that right?"

EM: "Look - freeze energy prices, break up the banks, other things I have said, change the way our economy works, I don't think we are cautious.

"We are not going to win this election by being cautious - we are going to win it by being bold and by being clear about how we are going to change the country.

"It is absolutely the person that I am, that is why I ran for the leadership.

"I ran for the leadership in difficult circumstances, everybody knows. I ran against my brother.

"Why did I do it? Because I felt I had something to say about how we change the country.

"That's why I am in this, that's what I want to prove over the next 12 months."

NR: "An energy freeze may be a good idea or a bad idea, no one will write about it in 100 years' time. They will write about what Attlee did, they will write about what Thatcher did. Are you saying you may not want to lay it all out yet, that this is a radical offer of a transformation of the way that Britain is?"

EM: "I think that I can substantially change the way our country works, because I think the central problem that we face - that countries around the world are going to face - in the coming years is: are you increasingly unequal, are you increasingly unjust, just working for a few people at the top of our society?

Mr Miliband and his wife met Alon Davidi, the Mayor of Sderot

"That requires big change not small change.

"Whether it was on energy - where I was massively criticised for the boldness of it - or on the banks or on other areas, we are going to make that change happen so our country truly works for people."

NR: "But more than once I have seen you praise Margaret Thatcher. Not for her ideas or her policies but as a person who brought about change."

EM: "I know where you are trying to tempt me towards.

"I think these comparisons with other historical figures have their limitations.

"I am going to be my own person and I am going to change the country in my own way.

"But if you are asking me if we need big change not small change? The answer is yes."

NR: "You know what I am asking you. Are you going to be Labour's Margaret Thatcher?"

EM: "Well no you don't make those comparisons. I want big change in the country, people yearn for big change."

NR: "If a commentator called you Labour's Margaret Thatcher then you wouldn't much mind?"

EM: "Well you can call me a radical. That's what I want to be. That is the kind of prime minister that I want to be."