Assisted dying law would lessen suffering says Falconer

- Published

- comments

Legalising assisting dying would mean "less suffering not more deaths", a leading campaigner has said.

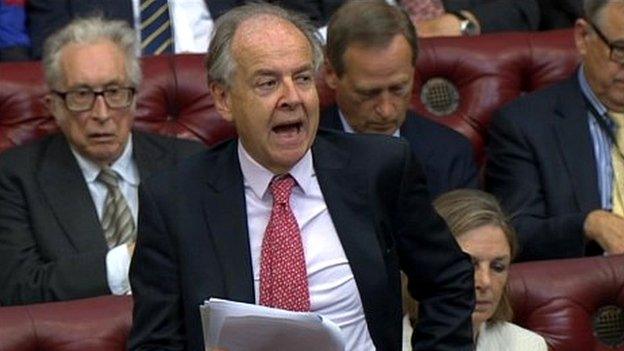

Lord Falconer, whose private member's bill, external would legalise the practice for some terminally ill patients, said a "limited" change was needed to the law to give people choice on their deaths.

But Lord Tebbit said it would create "too much of a financial incentive for the taking of life".

The bill passed its second reading in the Lords on Friday without a vote.

The proposed legislation would allow doctors to prescribe a lethal dose to terminally ill patients judged to have less than six months to live.

Making the case for his bill, Lord Falconer insisted that the "final decision must always be made by the patient", with safeguards to prevent "abuse"

About 130 peers requested to speak in a debate that lasted for around 10 hours.

'Lonely death'

The bill will now be examined line-by-line by peers in the Lords as it passes to committee stage.

However, without government backing, MPs are unlikely to get a chance to debate it in the Commons, meaning it will not become law.

Prime Minister David Cameron has said he is not "convinced" by the arguments for legalising assisted dying but the bill has won the backing of Lib Dem Care Minister Norman Lamb.

Lord Falconer made the case for a change in the law on Friday

The legislation would allow a terminally ill, mentally competent adult, making the choice of their own free will and after meeting strict legal safeguards, to request life-ending medication from a doctor.

Two independent doctors would be required to agree that the patient had made an informed decision to die.

Opening the debate in a packed house, Lord Falconer - a former Labour Lord Chancellor - told peers the current legal situation permitted the wealthy to travel abroad to take their own life while others were left "in despair" to suffer a "lonely, cruel death".

"The current situation leaves the rich able to go to Switzerland, the majority reliant on amateur assistants, the compassionate treated like criminals and no safeguards in terms of undue pressure now," he said.

He said many people were so worried about "implicating their loves ones in a criminal enterprise" by asking them for help to die that they took their lives "by hoarding pills or putting a plastic bag over their heads".

Baroness Wheatcroft say her mother was in agony and "would have used a loaded gun"

Legalising assisted dying, he argued would allow a "small number" of people who didn't want to "go through the last months, weeks, days and hours" of life to die with dignity.

Lord Falconer's bill was backed by Lord Avebury, the former Liberal MP, who was diagnosed with terminal blood cancer in 2011.

He urged peers to consider helping thousands of people whom he said faced "weeks of torture before they die a means of escaping from that unnecessary fate".

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Carey said he had changed his mind about the issue and now believed that belief in assisted dying was "quite compatible" with being a Christian.

"When suffering is so great, when some patients already know that they are at the end of life, make repeated pleas to die, it seems a denial of the loving compassion that is the hallmark of Christianity to refuse to allow them to fulfil their clearly stated request," he said.

Assisted dying debate

What is the current law on assisted dying around the UK?

The 1961 Suicide Act makes it an offence to encourage or assist a suicide or a suicide attempt in England and Wales. Anyone doing so could face up to 14 years in prison.

The law is almost identical in Northern Ireland. There is no specific law on assisted suicide in Scotland, creating some uncertainty, although in theory someone could be prosecuted under homicide legislation.

Have there been any previous attempts to change the law?

There have already been several attempts to legalise assisted dying, but these have been rejected.

The Commission on Assisted Dying, established and funded by campaigners who have been calling for a change in the law, concluded in 2012 that there was a "strong case" for allowing assisted suicide for people who are terminally ill in England and Wales.

But the medical profession and disability rights groups, among others, argue that the law should not be changed because it is there to protect the vulnerable in society.

What is the situation abroad?

In other countries, such as Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, legislation has been introduced to allow assisted dying. France is considering a possible introduction of similar legislation, although there is opposition from its medical ethics council.

Campaign group Dignity in Dying predicts that a lot more countries will follow suit.

But the Archbishop of York, Dr John Sentamu, said the proposed legislation was "not about relieving pain and suffering" but was based on the misguided belief that "ending your life in circumstances of distress is an assertion of human freedom".

'Confronting mortality'

Opponents of assisted dying protest against a change in the law outside Parliament

Actress Susan Hampshire leads a demonstration in favour of a change in the law

He told peers that his mother had been given weeks to live after being diagnosed with throat cancer but, with the help of others, had lived for a further 18 months.

"Dying well is a positive achievement of a task which belongs to our humanity," he said.

Calling for a Royal Commission to be set up to examine the issue, he added: "This is far too a complex and sensitive issue to rush through Parliament and to decide on the basis of competing personal stories."

Former High Court Judge Baroness Butler-Sloss said the proposed safeguards were "utterly inadequate" while former Tory cabinet minister Lord Tebbit said it could put pressure on people who are unable to care for themselves to "do the decent thing in order to cease to be a burden on others".

Lord Tebbit, whose wife was paralysed in the 1984 Brighton bombing, also suggested legalising assisted dying could lead to personal and financial disputes between loved ones and relatives.

"The bill would be a breeding ground for vultures, both corporate and individual. It creates too much financial incentive for the taking of life."

The BBC's parliamentary correspondent Sean Curran said the future of the legislation - and whether it ever makes it to the House of Commons - will be decided after the summer recess.

- Published17 July 2014

- Published16 July 2014

- Published17 July 2014

- Published10 September 2015

- Published21 October 2012