Fracking threatens tremors in general election

- Published

"Every time ministers open their mouths to claim that fracking must start everywhere around Britain, and not just in carefully selected and remote areas, they lose thousands of Tory votes."

These words, from George Osborne's father-in-law Lord Howell in May this year, go some way to explaining why fracking - the process of extracting natural gas from shale rock - is already one of the issues to watch out for in the run-up to next year's general election.

The coalition government has thrown its support behind it, with an Infrastructure Bill containing measures to change trespass laws to facilitate fracking, incentives offered to local communities for accommodating fracking, generous tax breaks for the fracking industry, and a new oil and gas "licensing round" which has opened up almost half the country to the potential of exploratory drilling.

Although the government's position is clear, it is less so within political parties.

Lib Dem 'disquiet'

The Conservative Party's enthusiasm for fracking is, officially, supported by the Lib Dem leadership. The Liberal Democrat conference in 2013 approved a motion on fracking, with Nick Clegg adopting a tone of cautious support and highlighting the value of domestically-sourced gas.

Lib Dem Ed Davey, Energy and Climate Change Secretary, believes that "UK shale gas can be developed sensibly and safely, protecting the local environment, with the right regulation". However, the party generally is much more divided.

Lib Dem MP Martin Horwood claims "there is a huge amount of disquiet about fracking within the party". Opponents of fracking range from party president Tim Farron down to Lib Dem grassroots members, who are anxious to maintain their green credentials.

But after a term in government, the Lib Dems cannot rely on being the default choice on this sort of issue for protest voters.

The UK Independence Party, which has moved above the Lib Dems in many recent opinion polls, has appeared to be the most enthusiastic of the four largest parties on fracking.

Labour's policy is that it wants tougher conditions - including 12 months' monitoring of condition before drilling to ensure there is a robust baseline against which to check whether any seismic activity or methane in groundwater is the result of fracking

But, the party says, "provided it can be done in a safe and environmentally sustainable way, we will support shale gas exploration".

On a visit last year to Lancashire - one of the UK's fracking hotspots where exploratory drilling is already taking place - Ed Miliband said: "I think we've got to look really carefully about this. There's strong local feeling and we've got to look at, and investigate, the issue very seriously."

'Political price'

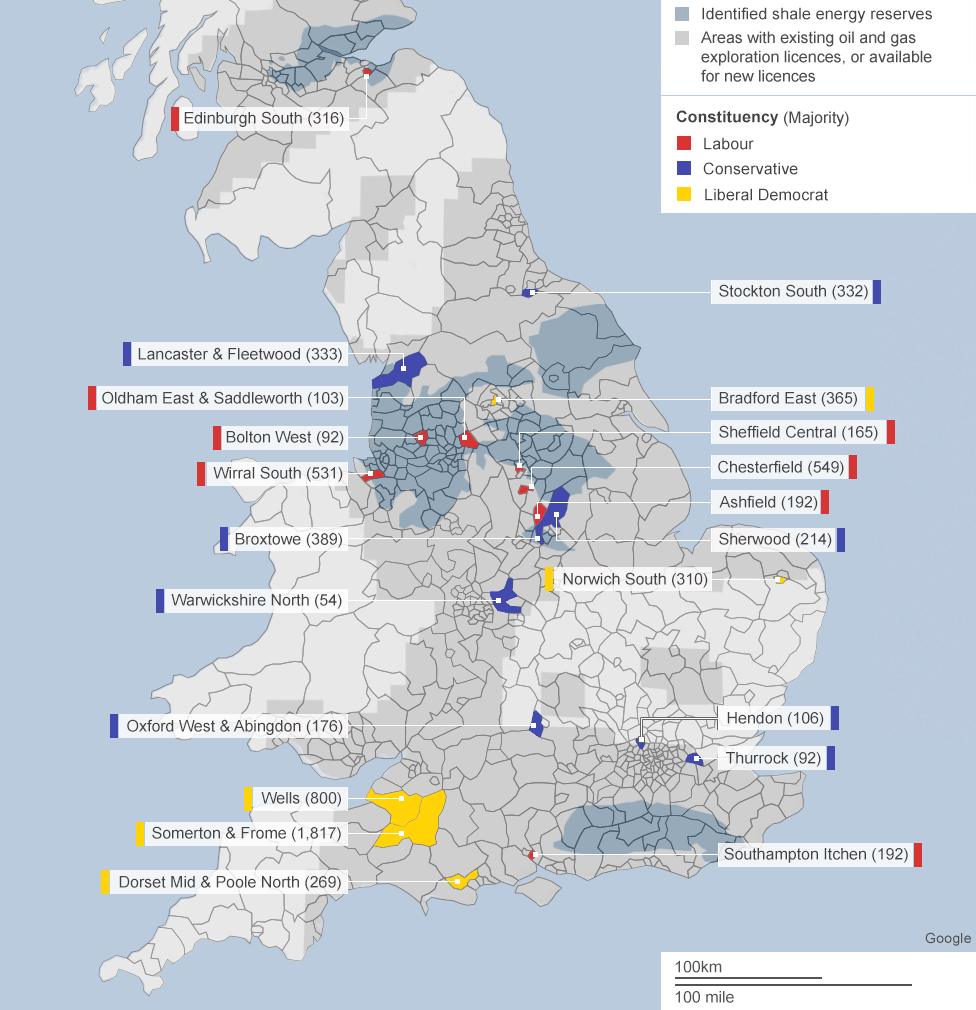

There are three areas of the UK identified by the British Geological Survey (BGS) as having significant shale gas reserves - the Bowland basin of north-west England, the central belt of Scotland, and the Weald Basin in south-east England.

Many pockets of these areas are already licensed for exploratory drilling, and have seen numerous anti-fracking protests.

On 28 July the government opened up lots more of the UK to oil and gas exploration.

Greenpeace UK energy campaigner Louise Hutchins says: "Now that the government has auctioned off half of the country to this controversial industry, there's going to be a hefty political price to pay… this is likely to prove a highly toxic policy cocktail in the run-up to the next elections, especially in marginal seats and key battlegrounds, where every vote counts."

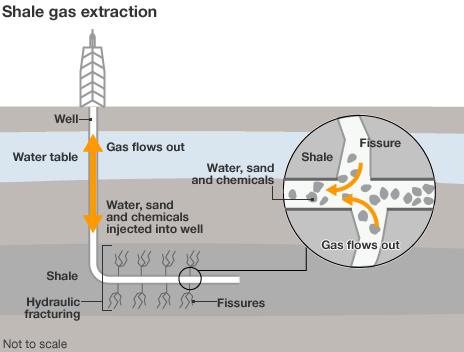

The BBC's David Shukman explains how fracking works

Areas of Labour support are the most affected by the latest round of fracking licences.

Greenpeace analysis shows that exploratory drilling could be permitted in more of their seats - 238 - than those of the other parties, including several Labour seats with very slim majorities in Bolton West, Oldham East & Saddleworth and Sheffield Central.

Exploratory licences are available in many traditional Conservative heartlands. The Weald Basin covers areas of Kent, Sussex, Hampshire and Surrey, where Michael Gove, Francis Maude, Philip Hammond, Chris Grayling and Jeremy Hunt all sit.

According to Greenpeace, 31 out of the 40 key marginal seats outlined in the Conservatives' election strategy fall into areas where exploratory drilling has now been permitted. The same is true for the majority of cabinet members' seats (although David Cameron's Whitney constituency is excluded).

Whilst it is true that MPs do not have any direct impact on fracking licences - it is the responsibility of local councils to deal with applications - MPs are the ones who are most likely to feel the force of public anti-fracking wrath. It will be their names on the ballot paper in 2015.

The University of Nottingham has been conducting a survey of public attitudes to fracking in the UK since March 2012. Their May 2014 summary suggests that while opposition to fracking in the UK has deepened, Conservative supporters are far more likely to be in favour of the process than Labour supporters.

Nimbyism

However, political affiliation is by no means the only factor that influences views on fracking. The issue will vary in importance depending on location - the level of Nimbyism involved in political decision making cannot be understated.

This is true not only of voters themselves, but of individual councils, some of which are prepared to flout the party line to oppose fracking in their area.

For example, the government's most enthusiastic backer of fracking, George Osborne, has found himself at loggerheads with the local council in his own Tatton constituency.

Further cross-party divisions have appeared, too. In January this year, a group of MPs from the three main parties and council leaders came together to call for a greater share of potential fracking profits for their Lancashire constituents.

With the issue dividing people according to political affiliation, location and personal opinion, who voters turn to if they wish to cast an anti-fracking vote is a critical question.

BBC political research editor David Cowling says: "If opposition to fracking is to have any influence on the 2015 general election, it is most likely to be in those few areas where the process is already well advanced.

"But if none of the main parties is opposed to it, who do the dissenters vote for? Possibly either the Greens or independent 'anti-fracking' candidates.

"If so, any political impact on individual seats is difficult to forecast... but it's likely to cause a few main party candidates some sleepless nights before polling day."

- Published23 May 2014

- Published4 June 2014

- Published11 August 2014

- Published28 July 2014

- Published3 July 2014

- Published8 May 2014