Analysis: Can extremism plan work?

- Published

- comments

Home Secretary Theresa May explains what new powers on extremism will mean

For years, ministers and policymakers have argued over the response to extremism because they have never been quite clear how to define it.

Now, after many years of behind-the-scenes wrangling, a Conservative home secretary is nailing her colours to this particular mast.

There are three prongs to her planned changes to how the government tackles extremism:

New powers to ban extremist groups

New powers to curtail the activities of individual extremists

Bringing the entire strategy under her control

The first two are General Election manifesto pledges so their future is down to you and the ballot box.

The decision to bring extremism strategy into the Home Office is already policy - and it is about more than rearranging the machinery of government: It’s a symbol of the tensions inside Whitehall over whether every previous attempt to combat extremism has been a muddled flop.

Labour sent extremism to the Department of Communities because it was wedded to a holistic - perhaps utopian - effort to create cohesive communities.

Its return to the Home Office ultimately means extremism will first and foremost be a security issue. The idea that radical and extreme ideology forms part of a “conveyor belt” towards terrorism will be firmly and finally embedded in policy.

The banning orders are a new idea.

The government can already ban organisations linked to terrorism - meaning actual violence or its incitement. This power has been used to proscribe 74 organisations, external - everyone from the IRA to Muslims Against Crusades, the group that staged demonstrations against soldiers returning from Afghanistan.

These counter-extremism banning orders go further. They would allow ministers to outlaw a group if it:

Spreads, incites or promotes hatred against a person or group

Seeks to overthrow democracy

Causes some kind of public harm, such as leaving people in fear and distress.

If such banning orders came in, they could lead to a considerable curtailment of public or online comment and campaigning.

Far-right groups prone to marching near mosques while chanting “Muslim bombers off our streets” could be a thing of the past. Hardline Islamist groups that declare they want the “black flag of Islam” flying over Downing Street may disappear from view.

These banning orders would work hand-in-hand with proposals to restrict individuals under “extremism disruption orders”.

You can decide for yourself whether supporters of such groups would change their minds just because they can no longer say what they think in public.

Greater good

The extremism disruption orders, or “Exdos”, would operate in the same way as an Asbo.

The authorities would have to prove to a judge in a civil court that somebody’s behaviour needs to be restricted for the greater good.

The court could impose conditions including banning someone from speaking in public, in social media or on the news. There could be restrictions on who they could associate with and bans on them taking a position of authority, such as becoming a school governor.

Just as with Asbos, the individual could face prosecution for breaching the Exdo.

Is any of this workable?

The experience of Asbos is that they can be very hard to obtain and to enforce because of the sheer effort required to gather enough evidence to satisfy the courts.

Judges are never reluctant to jail violent criminals who pose a danger to the public: these people have either pleaded guilty to a crime or been found guilty by a jury of their peers.

But courts have often struggled with Asbos because they don’t involve a criminal allegation.

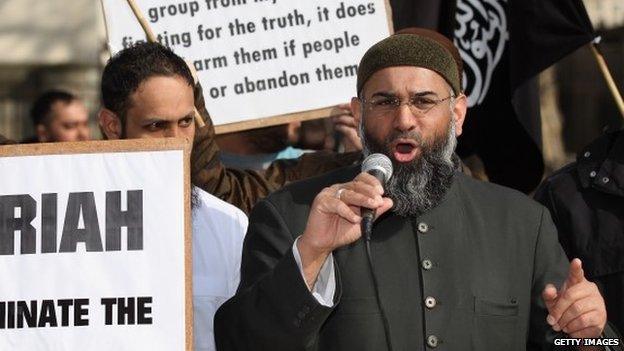

Anjem Choudary

Given the police and MI5 are pre-occupied with dealing with terrorist threats, who would gather and present the evidence? Given the bile that is regularly spouted on Twitter, how many of these people would be subject to the restrictions?

If some of the evidence were drawn from intelligence assessments, would MI5 and police counter-terrorism teams suddenly allow their secrets into the courts? That’s very unlikely - raising the possibility of secret hearings.

The closest comparable powers are police bail conditions imposed on someone who is under investigation.

Last week the controversial Islamist preacher and political activist Anjem Choudary, and his associates, were arrested as part of an investigation into their activities. Almost all of the men were later bailed - but police have banned them from talking to each other or proselytising on the streets.

It’s not stopped the men speaking to the media or online - within hours of his release, Mr Choudary met me on a London street to denounce Parliament's decision to join military action in Iraq.

Which brings us to the most controversial question about this package: Does it undermine the very values the government is setting out to defend?

The former Attorney General Dominic Grieve QC says that he is concerned that extremism powers could result in people being prosecuted for having a point of view. He warns that could fuel resentment and the Home Secretary would have to convince MPs why extremists could not be prosecuted under existing hate crime laws.

Former Attorney General Dominic Grieve: "It could simply fuel resentment"

The proposed restrictions on speaking in public are far, far wider than the 1980s broadcasting ban on Sinn Fein. They would almost certainly come under immediate legal attack on the basis that English law protects free speech, as does, to some extent, the European Convention of Human Rights.

The move also runs contrary to a policy position that’s less than a year old. Last December, the government’s Extremism Taskforce, chaired by the PM, said: "While protecting society from extremism, we will also continue to protect the right to freedom of expression, external."

Critics will say that the government's position has now been ditched - and the home secretary is arguing that the only way to protect our democracy is to prevent free speech.