Was Guy Fawkes a fall guy?

- Published

Executed, vilified, remembered: do we know the real Guy Fawkes?

He is the most notorious of traitors to the British Crown.

Who now can immediately name William Joyce as Lord Haw-Haw, English propagandist for Nazi Germany? Or Roger Casement, who canvassed for German support for the 1916 Easter Rising? Or the British Free Corps, a unit of the Waffen-SS formed of British men? Individual names haven't made it out of the history books.

In contrast, each schoolchild in Britain learns the story of Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot,, external and every year we burn his effigy to the accompaniment of fireworks.

But have we been commemorating a triumphant victory of the law over a violent usurper, or slandering the memory of an unwitting dupe?

The 'desperate remedy' of regicide

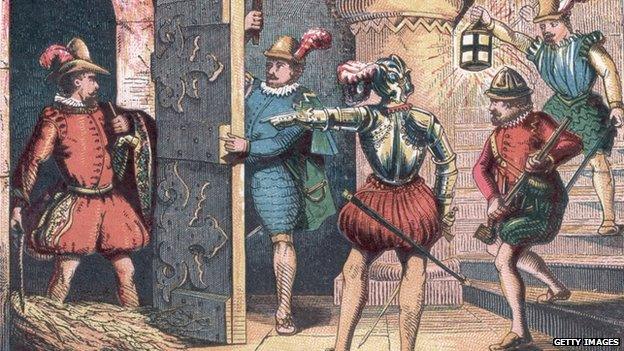

Fawkes was captured at what would have been the scene of the crime

The story is well known.

A group of Catholic conspirators were aggrieved at anti-Catholic sentiment and a lack of tolerance from new king - and professing Protestant - James VI and I.

They sought to blow up the House of Lords with gunpowder during the State Opening of Parliament in November 1605, killing the monarch and a vast number of the kingdom's luminaries.

From there, a Catholic vanguard of nobles would - it was hoped - shepherd the country back to the true faith.

Unfortunately for the rebels, someone in the know sent a letter to Lord Monteagle - a Catholic - advising him to avoid the ceremony in the Lords that day. Suspicions raised, the Palace of Westminster was searched - and Guy Fawkes was discovered alone in the cellars, surrounded by gunpowder.

After torture, he revealed his complicity in the plot but refused at first to give up his co-conspirators, most of whom fled or perished in a skirmish with the Crown's forces. Those remaining - Fawkes most prominently - were hanged, drawn, and quartered.

But how about this as an alternative version of events? Robert Cecil, adviser to the king and latterly a "spymaster" of Jacobean Britain, plots to discredit the reviled Catholic minority.

Through Thomas Percy, he organises a band of disaffected Catholic gentlemen, led by Robert Catesby, to blow up the king and entire political elite.

Cecil promises that they will be immune from punishment when the plot is officially discovered. This core group then secures the services of a number of men, unaware that the plot is a set-up, to take the fall.

Mark Nicholls, fellow in history at St John's College, Cambridge, notes that theories "that the government either knew of the conspiracy from an early stage, or that it actually manipulated the agents through one or more agents provocateurs" are "as old as the treason itself".

Writing as Guy Fawkes's biographer in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, external, Dr Nicholls says such theories "draw unwarranted conclusions from the surviving evidence" and "fail to advance any credible motive for such chicanery".

But what is the substance of these theories?

Cui bono - who benefits?

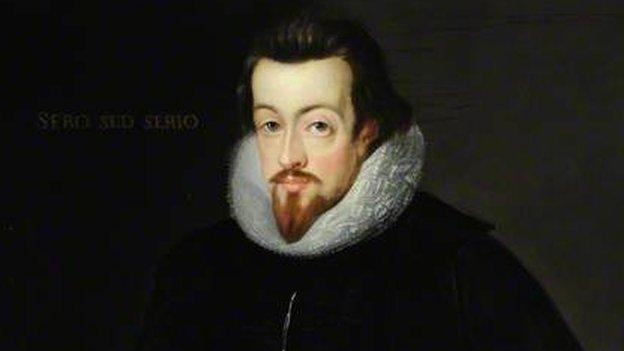

Robert Cecil, the Jacobean 'spymaster', as painted by John de Critz the Elder

Start with the motive. Those who believe the Crown was involved argue that the king's agents were eager to cause an anti-Catholic frenzy that would allow them to pass a raft of repressive measures and shore up support for the king - who was only recently arrived from Scotland.

Robert Cecil was a well-known anti-Catholic propagandist. His father, William, had performed a similar function for Elizabeth I. Leanda de Lisle, author of the book After Elizabeth: How James King of Scots Won the Crown of England in 1603, says that the Cecils "provoked conspiracies and were involved in a particular propaganda line against Catholics from the 1550s".

Did Robert Cecil tell the conspirators they would be immune from execution? Was he the source of the letter to Lord Monteagle?

Dr Nicholls is sceptical: "If this was a fashioned plot, it was extraordinarily ham-fisted."

He argues that those who would charge shadowy state forces with malicious intent ignore a central truth - that the revelation of the plot was "hugely embarrassing".

James had promised to leave Catholics alone, provided they practised in private and affirmed their loyalty to the Crown publicly.

The fact that a group of Catholics had conspired to kill the king - and a goodly portion of the country's senior political leadership - was hardly the advertisement for the unity of the new joint kingdom that its monarch desired.

Nor did the fact that they almost succeeded inspire confidence. Would a government inside-job have wanted to display the vulnerability of the king?

And far from seeking to immediately repress the Catholic population, in proroguing Parliament on the 9 November James - with calculated magnanimity - told his nobles to go back to their lands and reassure the people that it was a minority of Catholics who were responsible.

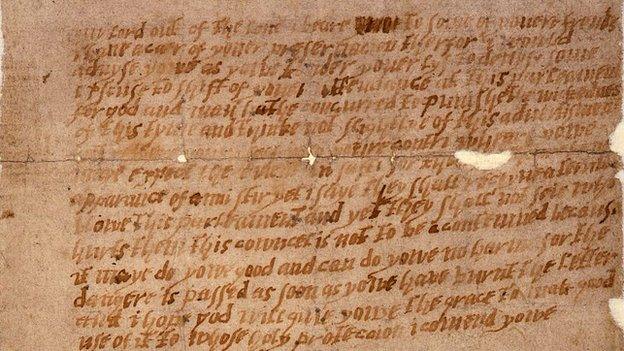

The letter to Lord Monteagle was unsigned

Where the modern conspiracy theorists go wrong, according to Dr Nicholls, is in their view that English Catholicism in the early 17th-Century was a homogenous group. In fact, it was a "divided, suffering community", most of whom were appalled by the actions of a few gentlemen, and feared being persecuted as a result.

According to Eamon Duffy, emeritus professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Cambridge, the plot "cemented into place what had been a major theme of anti-Catholic propaganda" in the previous decades: namely, that they could not be loyal.

But as a group, English Catholics escaped violent reprisal. Instead, the occasion was turned into the annual celebration of "anti-popery" and Protestant fervour that has lasted - in some form - to the present day.

And the letter to Lord Monteagle? Probably Francis Tresham, the Catholic noble brought into the plot late and uneasy about regicide. Guy Fawkes later told the authorities that Tresham - whom he had never met - had, according to fellow conspirators, been "exceedingly earnest" in previous discussions to warn Monteagle to stay away from Parliament.

The method

Fawkes was discovered in the gunpowder cellar alone

What about the logistics? One of the most common arguments for Crown involvement is that only the state possessed gunpowder - especially in the quantities required to blow up a large building.

This myth is "nonsense", says Dr Nicholls. The fact is almost every gentleman in early 17th-Century Britain would have had a stock of gunpowder.

Quite simply, it would have been very easy to acquire the gunpowder - which, although weighing in at almost a tonne, still only took up 36 barrels. It was moved across the river slowly but steadily.

Some also maintain that the nine-day delay between Monteagle's receiving the letter and the search that discovered Fawkes is evidence of sinister intriguing at the highest levels of power.

But nine days may have been needed to investigate the letter, protect the king, and find evidence of treason.

Another argument is based on the career of Sir Thomas Knyvett, Keeper of Whitehall Palace.

Knyvett was the man who conducted the search of the cellars underneath the House of Lords which uncovered Guy Fawkes. He was later given a peerage.

Doubters of the official version suggest that if the plot was simply a Catholic conspiracy to kill the king, Knyvett ought to have been disciplined for allowing the rebels to rent the cellar directly below the House of Lords.

But how involved would he have been in a relatively trivial property decision? And the peerage would hardly have seemed remiss as a reward for performing a great service to the Crown, and in recognition of a long career at court.

As for the premises that became available just as the original plan - to tunnel through the walls of parliament - was being frustrated, on such strokes of fortune does history turn.

Fawkes the prisoner

Fawkes's torture was personally sanctioned by the king

The fact that Guy Fawkes became the face of the Gunpowder Plot indicates to some that he was simply a stooge whose memory was exalted to spur an annual festival of anti-Catholic revelry and remind people that God had spared the king from a violent fate.

But Fawkes had a history of seditious behaviour, and was a devout Catholic. He was selected to protect the gunpowder and light the fuse because of technical expertise with mines and explosives acquired fighting for Catholic Spain against the Protestant Dutch Republic.

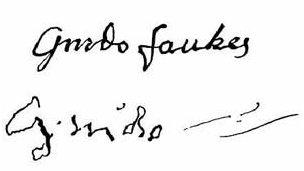

Fawkes's signature before and after days of torture

Alone among the rebels, Fawkes was tortured, but despite admitting his own guilt he refused to incriminate his co-conspirators, buying them what Dr Nicholls calls a "critical 48 hours" to rally themselves in their Midlands homes and prepare for an assault by the Crown forces.

Although the rebellion ended in desertion and death, and Fawkes signed a confession in famously dishevelled handwriting after days of torture, his courage in captivity was notable. Would such a character have been the patsy for a government stitch-up?

Fawkes the legend

Lewes in East Sussex hosts the most renowned festivities in Britain on the 5 November every year

Why does the story still strike a chord? Why do we still commemorate the foiling of the plot on 5 November?

According to Dr Nicholls, what has made the holiday endure is its "tremendous versatility" over the centuries - "its ability to lose its religious connotations".

"It can take the form of a protest against the state, against individuals, against a particular religion."

Undoubtedly, it is also just a wonderful opportunity to "let off some steam".

And why does the conspiracy itself hold such appeal? It is the "quintessential conspiracy", he says, with powerful men "huddling in the corner, taking oaths of secrecy, having furtive meetings".

Of course, it is possible that the hidden hand of Robert Cecil was at work throughout the plot; perhaps he was such a master of espionage that his role in the proceedings is so well-concealed and obscure that even our finest historians have not unearthed evidence of him pulling the strings.

With heroes and villains marked by shades of grey, and the realities of deeply felt faith in Jacobean Britain, the story lends itself to over-interpretation.

But as the fireworks light up the night sky on Wednesday, who would really want to deprive Guy Fawkes and his conspirators of the notoriety his story has gained over the past 409 years?