Mandy Rice-Davies and a classic Westminster scandal

- Published

The Profumo scandal, involving Mandy Rice-Davies, was an explosive cocktail of sex, race and spying

Mandy Rice-Davies, who has died aged 70, was, along with her friend Christine Keeler, at the heart of a classic political scandal.

The Profumo affair was a sinister cocktail of high-society vice, drugs, race - one of the bit-part players was a West Indian - and espionage. It spilled on to the floor of the Commons and mortally wounded a prime minister.

John Profumo's demise was summed up in a neat piece of doggerel: "To lie in the nude may be rude, but to lie in the House is obscene."

His indiscretions would probably have been fatal to a cabinet minister in a highly sensitive post - but what sealed his doom was that he told a direct lie to Parliament.

He was goaded into it by George Wigg, now an almost forgotten member of Harold Wilson's kitchen cabinet - his coterie of advisers, courtiers and odd-job men.

'Wiggery-pokery'

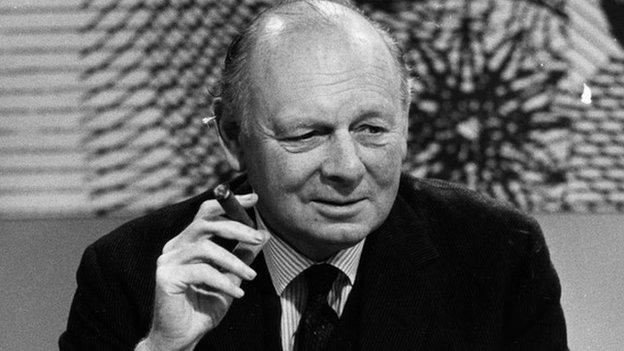

Wigg was known for his expertise in the political undergrowth - "wiggery-pokery" - and he had worked hard to ensure Labour exploited the series of murky sexual and spying scandals that dogged the latter part of Harold Macmillan's premiership.

With a fine grasp of parliamentary procedure and legal niceties, George Wigg brought the Profumo affair into the public domain with a Commons speech.

Harold Macmillan resigned just over six months after the scandal broke

"There is not an Hon Member in the House, nor a journalist in the press gallery, nor do I believe there is a person in the public gallery who, in the last few days has not heard rumour upon rumour involving a member of the government front bench," he said.

"That being the case, I rightly use the privilege of the House of Commons - that is what it is given to me for - to ask the home secretary, who is the senior member of the government on the Treasury bench now, to go to the Dispatch Box.

"He knows that the rumour to which I refer relates to Miss Christine Keeler and Miss Davies and a shooting by a West Indian... and, on behalf of the government, categorically deny the truth of these rumours."

That provoked a hurried meeting of cabinet ministers in which Profumo flatly denied any relationship

He also denied that the word "darling," with which he began an affectionate letter to Miss Keeler, which was then in circulation, amounted to a confession of adultery.

'No impropriety'

One of the ministers present, Iain Macleod, later told a journalist friend at the Spectator that he had posed the question in the most blunt terms - had they had sex? Startlingly, they believed his denial.

So John Profumo was sent into the Commons to deliver a personal statement on 22 March 1963. The key phrase was: "Miss Keeler and I were on friendly terms. There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler."

Nigel Birch's Commons refrain on the scandal entered the political lexicon

Caught out, he resigned.

George Wigg's intervention had lifted the lid on a web of intrigue in the upper echelons of society and a colourful cast of characters, including Stephen Ward.

The society osteopath was subsequently charged with living off the immoral earnings of Ms Rice-Davies and Ms Keeler.

Ms Rice-Davies, who never actually met Profumo, later testified at Stephen Ward's high-profile trial and became notorious for claiming to have had an affair with the peer Lord Astor and for dismissing his denial when in the witness box.

With Profumo disgraced, the political spotlight then turned on his prime minister.

Harold Macmillan came under sustained attack. His critics thought he'd handled what could have proved to be a grave national security scandal far too casually and should have realised he'd been lied to.

In the absence of an actual national security leak - there was no evidence that any information had found its way from John Profumo to one of Christine Keeler's other boyfriends, a Soviet naval attache - that was the most deadly line of attack.

In a Commons debate, opposition leader Harold Wilson savaged the "indolent nonchalance of the prime minister's attitude", and attacked a decadent aristocratic elite for casually exploiting working-class girls and covering up the risks its conduct posed to national security.

But the killer blow came from a sacked ex-minister, Nigel Birch, who chose the debate to take his revenge.

'Lost leader'

With dismissive elegance, he skewered Harold Macmillan for accepting John Profumo's assurance that there was no impropriety: "There seems to me to be a certain basic improbability about the proposition that their relationship was purely platonic. What are whores about?"

Harold Wilson successfully portrayed the Conservatives as decadent and out of touch, winning the 1964 election

And he ended with a literary flourish - quoting lines from Robert Browning's poem, The Lost Leader.

"Let him never come back to us! There would be doubt, hesitation and pain. Forced praise on our part - the glimmer of twilight, Never glad confident morning again! Never glad confident morning again!"

The young Peter Tapsell - now the longest-serving MP in the Commons and the Father of the House - was sitting behind the prime minister, and could see him tense as he recognised Browning's lines and realised what was to come.

When the words were uttered, he recoiled as if slapped in the face.

Press comment on the debate and Macmillan's performance was scathing - "Mac: The End", "The Stag at Bay", "The Lost Leader", "A Broken Man Close to Tears". In his Diaries, Tony Benn wrote: "It is now only a matter of time."

That debate was in June 1963 - by October, the ailing Macmillan had resigned.

- Published19 December 2014

- Published25 February 2014